On the vast steppes of Eurasia, in an area the Greeks referred to as Scythia, lay the remains of a young woman approximately twenty to thirty years of age, dating back to the fourth century BCE. Although predictable feminine accoutrements, such as mirrors and jewelry, were buried alongside her, there were some unpredictable items around her as well. Two iron lances mark the entrance to her burial mound, along with an enormous armed leather belt, bronze-tipped arrows and various other instruments of war. Her deathblow came in the form of a battle-ax smashed through her skull demonstrating without a doubt that this woman was a warrior.

But as brave and daring as this young woman may have been, she was not an outlier. Thousands of burial mounds such as this one can be found from Bulgaria to Mongolia. Before the onset of DNA testing, these gravesites were believed to be those of male warriors. But we now know that in some areas fully thirty-seven percent of all the burial mounds excavated are those of female warriors complete with battle scars and surrounded by their tools of combat. In a time when women were seldom seen and almost never heard, could these plucky Scythian women be the famed Amazons for which Greek writers of antiquity were so fond of reporting?

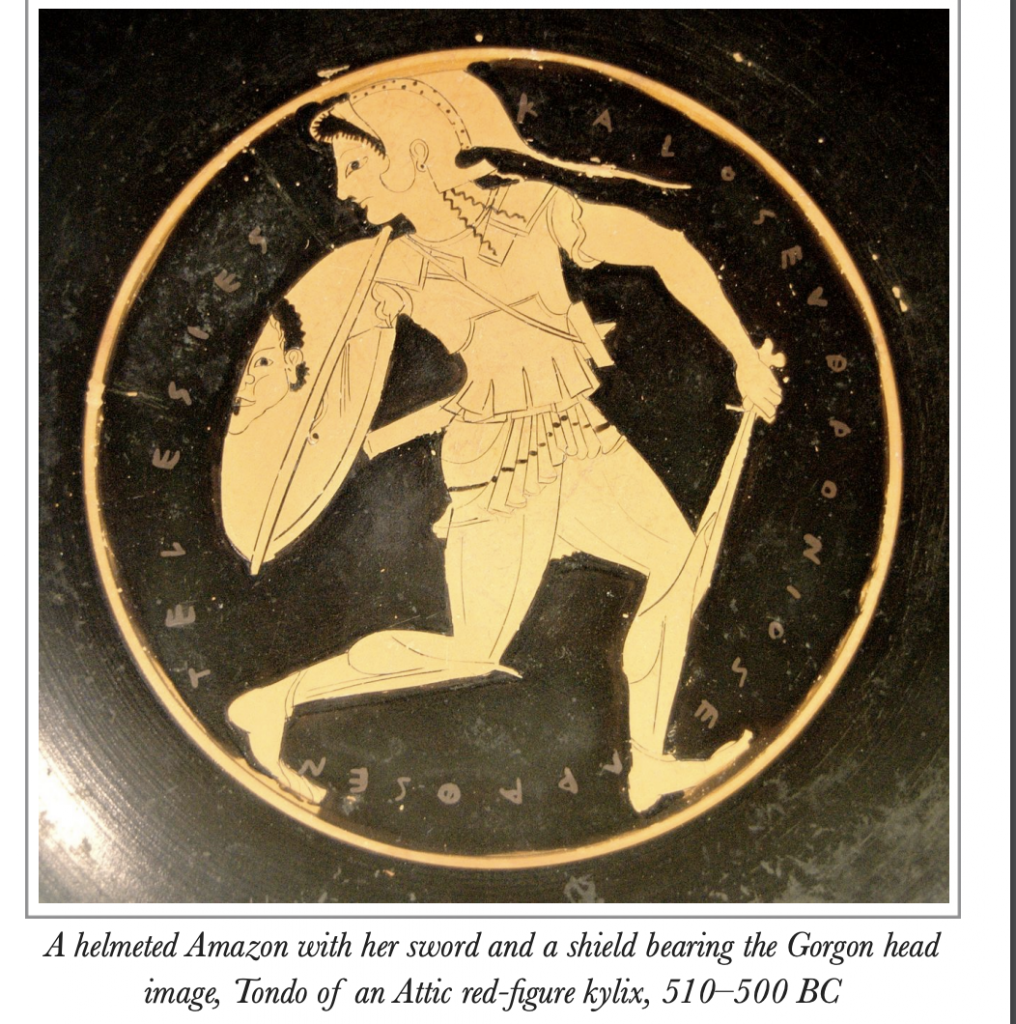

Steeped in Greek culture, the Amazons were a notorious force to be reckoned with for heroes and gods alike. From Homer to Herodotus, from Strabo to Plutarch, their stories were part and parcel of the Greek tradition. Interweaved in Greek mythology, Amazons were a popular theme in Greek art with their images and statuary adorning public, private and sacred spaces. In vase art the Amazons were second only in popularity to Heracles himself. To demonstrate how ingrained Amazons were in the Greek psyche, artifacts show that dolls with the Amazons’ distinctive headgear have been found in the graves of young girls in Greece and the surrounding area. But the question that has long vexed scholars throughout the ages is were they real or imagined? Although writers of antiquity wrote about the Amazons as historical fact, most latter-day historians believed that Amazons were the stuff of legends. Yet today it is no coincidence that the area pinpointed by Ancient Greek writers as home to the Amazons is also a region rife with the remains of warrior women. More and more scholars are revising their assessments about the authenticity of the Amazons as DNA testing is proving that the antiquarians may have been right all along.

But who were the Amazons? And how did they live? Eurasian women, in an area known as Scythia to the Ancient Greeks, highly resemble the caricature we have of the Amazons. Indeed, the ancients were well aware that the women to whom they referred to as Amazons were actually Scythians, a nomadic people who lived in a myriad of small tribes within the vast territory of Eurasia. Once Scythians began breeding horses, they flourished becoming famous for their mounted warfare. When the Greeks started establishing colonies along the Aegean coast of Anatolia from 1000-700 BCE, Scythians and Greeks began having skirmishes. Not coincidentally this was around the time that the Amazons began to capture the Greek imagination. In the eighth century BCE, Homer was the first to consider them in The Iliad, which is set in the Bronze Age (2800 BCE- 1050 BCE) several hundreds of years before Homer composed the epic. Yet the Amazons were not a Greek invention as some scholars have insisted over the years. In addition to Greek mythology, non-Greek narratives from such ancient cultures as Persia, Egypt, India and China include stories about nomadic warrior women as well. But alas, the Scythians themselves were pre-literate so we have come to rely heavily on Ancient Greek and non-Greek sources to fill in the blanks for us about their lives. Notwithstanding archeological and linguistic artifacts how else could we learn about the warrior women?

The truth is, though the Scythian nomadic culture was without writing, it was not without stories. These stories, called the Nart sagas, were an ancient oral tradition of the Caucasus reckoned to be as old if not older than Homer’s famous epics. The sagas depict a race of warrior horsewomen who strongly resemble our notion of the Amazons. Largely independent from the yoke of marriage, these women were courageous and forthright; characteristics the Greeks attributed exclusively to the male gender. Furthermore, the sagas suggest a possible etymological link to the word Amazon itself as one of their vignettes portrays a famous queen called Amezon. Woefully, life for a warrior woman was often dismal, to her misery Queen Amezon discovered that the warrior she killed in battle was none other than her beloved.

The name “amezon” is an example of the word in its native origin, but the Greeks had their linguistic equivalent of “amazon” as well. One persistent myth that has dogged the Amazons has an etymological link to their name. Most archeologists now agree that Amazons did not cut off their right breasts— or any breasts for that matter— yet the myth of their only having one breast has endured throughout the ages. Why the tale? Perhaps the reason lies in the word “Amazon” itself. Broken down etymologically in Greek “a” meant without and “mazos” means breast. Were the ancient Greeks trying to make the Scythian women look even more exotic than they were, putting a further distance between them and their secluded Greek counterparts? To be sure, the chasm between Greek women and their nomadic sisters was wide enough already without the single-breasted fable as the two cultures were poles apart in their treatment of the fairer sex.

In this resource scarce nomadic society, everyone was expected to pitch in to do his or her part. Indeed, scarcity became a great liberator as girls trained right alongside boys in hunting and warfare. After all, females were just as effective at riding horseback, thrusting spears and slinging arrows as their male counterparts. It should be noted that although warrior women likely fought together as a group, as yet there is no evidence to support that the Amazons existed as a society onto themselves without males, as the Greeks attested. In fact, burial grounds from the region demonstrate that warriors, both men and women, lived together as a populace.

Because there was no set age for marriage, nomadic women and men were free to commingle with each other before marriage and even to take on other lovers after marriage. Seasonal patterns are typical in nomadic life as they migrated from pastures in the summer to camp-sides in the wintertime. Each spring brought bands of tribes together as a means of forging alliances. Thus, intertribal unions were accepted and even commonplace. Many experts assert that in most tribes, women were warriors until they had children at which point, they stayed with their kin; that is unless a mother chose to fight. It is believed that a woman had some agency in how she wanted to live, though primarily young or child-less women were the warriors.

It must have been astonishing for Greeks to discover the freedom afforded unattached nomadic women. After all, Greek girls, no more than fourteen or fifteen years of age were more often than not kidnapped by their suitors then confined in marriage to a life of servitude and domesticity. In direct contrast, amongst the nomadic tribes, competition between males and females was frequently encouraged. One account holds that if there was an interest in marriage on the part of the male then he had to wage a battle with his beloved. Whereas most fights were to death, this fight was to love with the winner seizing control of the reins throughout their marriage. As marriage was not rigged in favor of the male from the onset, there was some parity between the lovers, something utterly foreign to the Greek way of thinking.

Make no mistake, despite the tall tales of man-haters on the one hand or promiscuous vixens on the other, Greeks admired even idolized the warrior women and have the stories to prove it. Three of Greek’s leading heroes had life-changing encounters with the race of warrior women. In the ninth of his twelve labors, Heracles was forced to strip the magical girdle off of their warrior queen, Hippolyte, one of the tribe’s fiercest fighters. Unsurprisingly, it did not go well for the Amazon queen. Never one to realize his own strength, Heracles, in an attempt to strip Hippolyte of her belt, ended up killing her. The second hero was Achilles who fell head over heels in love with another of their queens, Penthesilea. But tragically he discovered his attraction to her while they were engaging in hand-to-hand combat on the battlefield. Indeed, it was only after Achilles killed Penthesilea that he realized—alas too late— that he had fallen madly in love with her. And lastly, Theseus, the mythological first king of Athens, kidnapped then married Antiope, yet another Amazon queen and daughter of Ares, god of war, thereby making her queen of Athens and sparking a war between the Amazons and the Athenians.

In each of these vignettes, the Amazon either dies nobly at the hands of a Greek hero or in the case of Antiope is treated no worse than a Greek woman. Woefully, like Ariadne before her, Theseus ultimately betrays Antiope, instead making Phaedra his wife. Oh, thou fickle heart! Yet there is some consolation in knowing how his final marriage turned out. Joking aside, for all their misogyny no other “race” of people is handled as justly in Greek mythology as the Amazons. After all, Amazons were portrayed as being brave and daring, adventurous and enterprising, independent and forceful; qualities the Greeks had sorely discouraged amongst their women, much to their disadvantage. Perhaps life would have been more abundantly eclectic in Ancient Greece if we had heard as much from the second sex as we have from the first.

Although the myths are considered in the realm of fiction, the substance behind them is real; their content is palpable. Experts now maintain that it was not uncommon for women and men to engage in hand-to-hand combat. And conversely, in an example of art imitating life, it may not have been uncommon for Greeks and Amazons to fall in love. It should come as no surprise that the Greeks were enamored of the warrior women, as DNA testing has now shown, Amazons were tall, athletic and fair skinned, just like those in the Greek pantheon. Through the primordial haze of antiquity, we can start to make out the form and texture of the warrior women and the lives they led. We begin to see a shadow, a shrouded image; that which was hidden in obscurity for eons is coming into clearer focus. As never before Amazons are fast becoming well ensconced on the terra firma of historical fact. But alas, examining a pre-literate culture dating back over three thousand years has its distinct disadvantages. Although much has been discovered about their lives, much more still remains to be learned with the expectation and promise of further scrutiny and more scholarship to come in this area.

Published on Classical Wisdom