Born into a life of privilege, Julia’s world was sent into a tailspin when Augustus executed her husband, accusing him of conspiring to overthrow his rule. Without the protection and political backing of a husband, Julia was vulnerable; elite women in Ancient Rome were expected to rely on a male guardian or husband to protect their interests and reputations. Her status as a widow subjected her to social, legal, and political scrutiny, rendering her an easy target for scandal. Moreover, the severe Lex Iulia de adulteriis statutes allowed no exceptions for widows; extramarital affairs were deemed crimes against public morality.

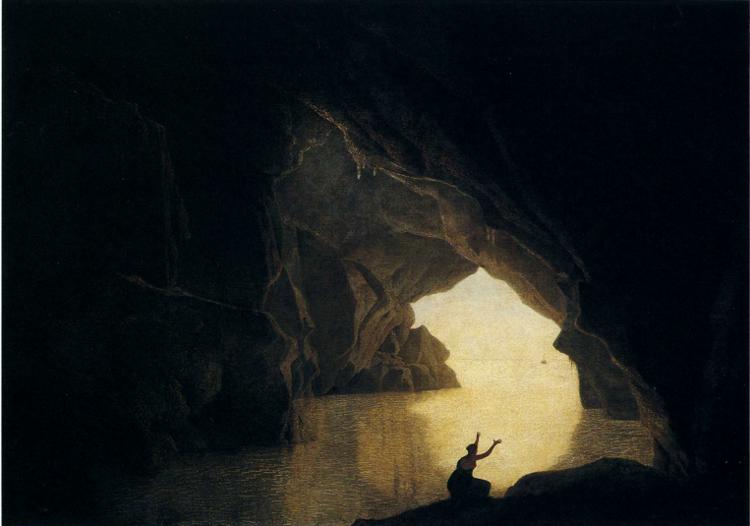

As if to uphold the law’s ignoble expectations, Julia’s unchastity was laid bare when Augustus discovered that the young princess had become pregnant—long after her husband had died. As punishment he permanently exiled her to the remote island of Tremirus (today’s Tremiti Islands) with limited access to the outside world, ordered the destruction of her lavish villa—on the pretext that it was too ostentatious—and decreed that she was not to be buried in the family mausoleum. But even these harsh penalties were insufficient to quell the emperor’s wrath. In his cruelest act, Augustus commanded that her newborn infant be exposed, leaving it to perish in the harsh, wind-swept terrain of the barren island, which Julia would call her home for the next twenty years, or until the end of her life.

Who was this enemy combatant whose family Augustus was bent on destroying? It was none other than his own. Commonly known as Julia the Younger, Vipsania Julia

Agrippina (19 BCE-28 CE) was Augustus’s eldest granddaughter; the eldest daughter of his only biological child, Julia Augusti Filia or Julia the Elder (29 BCE-14 CE), who herself had been exiled—for the same offense of adultery—ten years prior.

This essay examines Julia the Younger’s life and the times in which she lived. Without recording a single word she spoke, the ancient chroniclers were quick to depict Julia as frivolous and empty-headed, complicating our understanding of her true nature. Unfortunately, this unfair portrayal has persisted for over two thousand years, as modern historians have often taken the ancients’ accounts at face value. Moreover, because of the coincidence of their names and offenses, Julia’s narrative has been overshadowed by her mother’s, since the ancient chroniclers often grouped their stories together under the heading of loose women and designed their narratives around this leitmotif. Reduced to a mere footnote in the larger tale of her family’s cruel legacy, this paper endeavors to reveal the intricate aspects of Julia’s life and suggests a reevaluation of the accounts that have veiled her legacy.

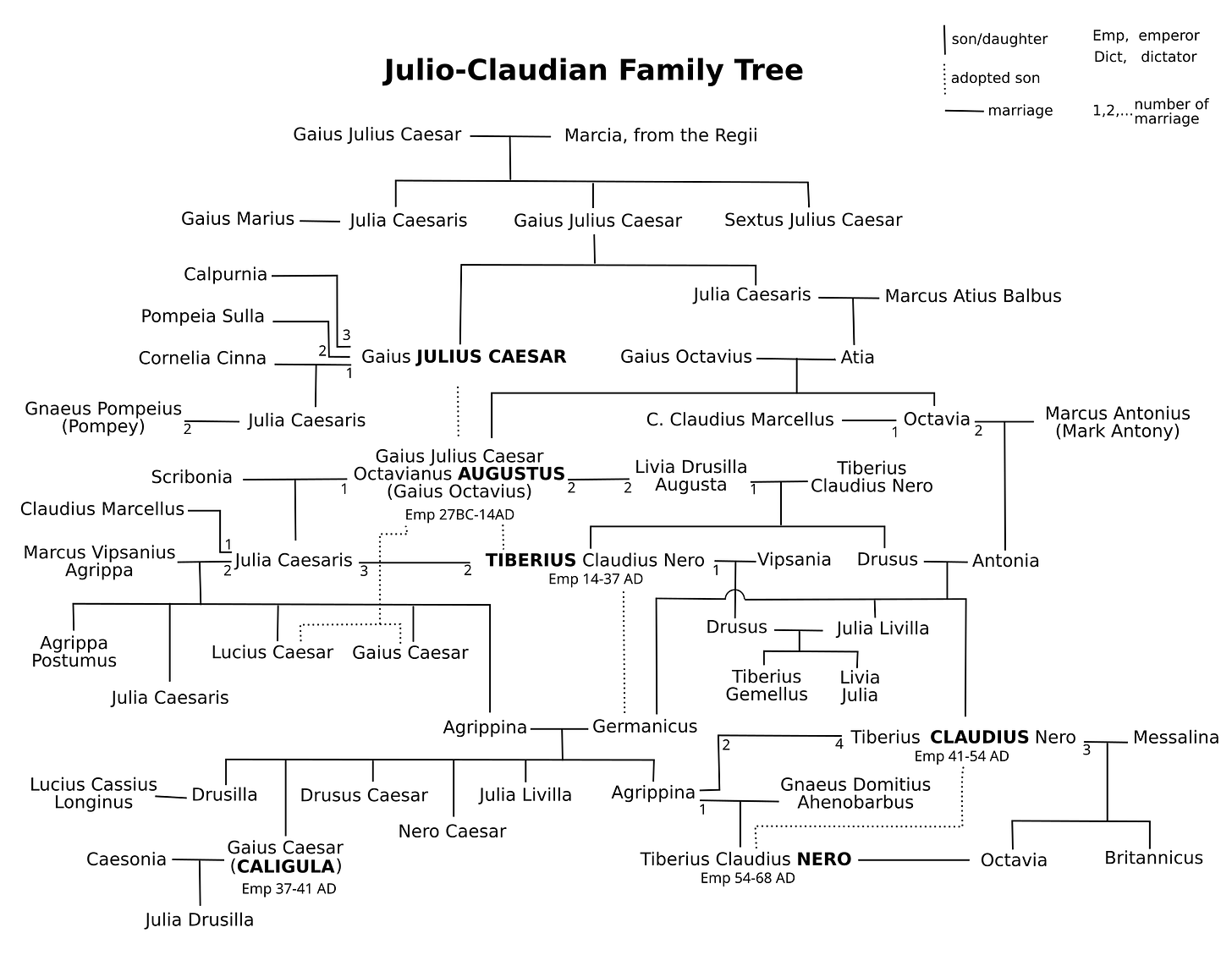

To avoid confusion Julia the Younger will be referred to as Julia in this paper, while her mother, Julia, will be referred as Julia the Elder. Julia was the second eldest of five children born to Julia the Elder and her second husband, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa—the general who all but won the Battle of Actium when Augustus was merely Octavian. Her mother was a key member in Augustus’s endeavors to fortify his dynasty through strategic marriages and the procreation of heirs. Her father, Agrippa died in 12 BCE at the age of fifty after falling ill on a military campaign when Julia was 7. However, long before Agrippa’s death, needing more fodder for his dynastic mill, Augustus took full ownership of his daughter’s and Agrippa’s two eldest sons, Gaius and Lucius Caesar, in 17 BCE. Numerous important legal and social actions were necessary to establish Gaius and Lucius as Augustus’s heirs and integrate them into the Julian family line which involved moving the child from one family (gens) to another. Adoption in ancient Rome was a complete and irrevocable affair in which the child officially became the adopted father’s, with no formal ties to his biological parents. In the case of Julia’s eldest brothers, they moved from the Vipsania gens to the Julio gens for the sole purpose of succession.

While Augustus was particularly focused on the upbringing of his “own two sons,” he also played a significant role in raising all of his grandchildren—including the females. Similar to his approach with his daughter, he enforced a strict regimen over them. Julia grew up in an environment where her education and social interactions were closely monitored by both the emperor and her ubiquitous step-grandmother, Livia. Even their guests faced scrutiny and required approval, making social interactions with peers a perilous undertaking. Striving for nothing less than perfection in the public image of the imperial household, Augustus expected the children’s behavior to reflect his high moral reforms—despite the fact that his own morality and that of Livia were compromised in that respect. All of Rome was aware that Augustus had pursued a pregnant Livia while they were both married to others, and he divorced his second wife, Scribonia, on the very day she gave birth to his only biological child, Julia the Elder.

From dawn until dusk, Julia’s days were full. Like all females in the Augustan household, she was required to learn traditional feminine tasks, such as spinning and weaving. In the Julio-Claudian family, the females were responsible for making all the clothing for the household. Nevertheless, similar to her brothers, Julia also received a

literary education. She was expected to memorize all of Homer’s works and become proficient in both Greek and Latin. Additionally, she acquired essential skills for elite Roman women, such as managing household affairs and participating in religious and social events.

Aside from playing a key role in raising his progeny, Augustus’s true talent lay in orchestrating marriages within his expanding dynasty. At the age of thirteen, Julia was betrothed to her maternal grandmother’s great nephew, her second cousin, Lucius Aemilius Paullus, who was eighteen years her senior. The bride’s tender age was typical among the Roman aristocracy, and the betrothal, orchestrated as a component of Augustus’s dynastic policy, maintained the consolidation of power within his family. After Augustus established his position as Princeps or first citizen of the state (he would never call himself emperor), intermarriage within the tight-knit Julio-Claudian clan became routine since it possessed the greatest advantage for consolidating power. This method reinforced familial bonds and ensured that power was concentrated among the lineage, frequently leading to intricate interpersonal dynamics, rivalries, and even, from time to time, familicide.

In just over a year, Julia transitioned from a teenage bride to a teenage mother, giving birth to her daughter, Aemilia Lepida, at the age of fourteen. However, her life took an even more dramatic turn when, at seventeen, Augustus accused her mother of adultery—without due process in a court of law—leading to her lifelong exile. By then, Julia the Elder was on her third marriage arranged by her father within several months of Agrippa’s death, this time to the sullen Tiberius. It was a doomed union from the start and one that would produce no surviving issue. Tiberius would eventually leave Rome and Julia behind and self-exile to the island of Rhodes—1100 miles or 1500 kilometers away. Lacking the protection of a husband or guardian, the vivacious Julia the Elder became involved with a cosmopolitan crowd that held more permissive views on infidelity than the emperor’s strict moral codes, the Lex Iulia laws dictated. In the historical record, Julia the Elder’s name became associated with several men from noble families, including Iulius Antonius, the son of Mark Antony. While exile to a desolate island awaited the emperor’s daughter, Iulius faced execution but beat them to it by committing suicide.

A teenaged Julia was never to see her mother again. The ancients are mute about how Julia must have felt losing her only surviving parent. In fact, the ancients are mute when it comes to much of Julia’s life. Treated as stock characters, the ancient chroniclers—most notably Tacitus, Suetonius and Cassius Dio— disregard females completely unless they distinguish themselves in a wayward manner.

Her mother’s infamy, however, did not prevent her husband Paullus from becoming consul in 1 CE. Furthermore, Julia the Elder’s notoriety did not adversely affect her younger daughter’s prospects for an advantageous marriage. In 5 CE, Augustus arranged for Julia’s younger sister, Vipsania Agrippina—who would come to be known as Agrippina the Elder—to marry his great-nephew, Germanicus, a celebrated war hero and the son of Tiberius’s deceased younger brother, Drusus.

By this point, both of Julia the Elder’s eldest sons—the heirs to the throne—had died within a span of eighteen months; Lucius succumbed to a brief illness in 2 CE, while Gaius died in 4 CE of an infected war wound. The losses of his two heirs were both personal as well as political for the emperor who was heavily invested in their futures. Yet, ever the pragmatist, Augustus wasted no time in adopting Tiberius as his heir and compelled him in turn to adopt Germanicus as his to secure dynastic succession. Moreover, in 4 CE, Augustus adopted Julia the Elder’s youngest son, Agrippa Posthumus—so named because he was born after Agrippa had died—but he was permanently banished in 7 CE, ostensibly for being of “illiberal nature.” Tiberius, concerned about his proximity to power, quickly eliminated him once he assumed regency.

The truth is, Augustus focused on succession because he had no biological sons. Livia, from her previous marriage to Tiberius Claudius Nero, brought two sons into the dynasty: Tiberius and Drusus. Augustus, however, had only one child from his second wife, Scribonia: Julia Augusti Filia (Julia the Elder). Despite their impressive lineage and a monumental fifty-one-year marriage, Livia and Augustus did not have any children who survived infancy. In contrast, Agrippina and Germanicus succeeded where Livia and Augustus had not, playing a vital role in uniting the Julio-Claudian bloodlines by having nine children, six of whom reached adulthood. Among their offspring were Caligula and Agrippina the Younger—the indefatigable mother of Nero.

From the outset, Julia’s marriage was less fortuitous than that of her younger sister. One historian notes that Augustus seemed eager to orchestrate Julia’s marriage at the age of thirteen to more quickly dispose of her. In contrast, he postponed Agrippina’s betrothal until she was nineteen, which was considered mature by ancient standards.

This delay allowed for a union with his preferred great-nephew, Germanicus, who was himself of Julio-Claudian stock. Germanicus was the maternal grandson of Octavia, Augustus’s sister, and the son of Drusus, the youngest son of Livia. Because of his overall popularity with the Romans (and with Augustus), he was being groomed for the throne. Of note, despite the significant differences in the sisters’ early fortunes, they shared the same grim fate. Under the Emperor Tiberius’s edict, Agrippina the Elder—like her mother and sister before her—was sent into exile. After four years, she died of starvation at age 47.

As for Julia, although Paullus served as consul in 1 CE—an office with a one-year term—he disappears from the historical record until his ignominy in 6 CE when he is convicted of maiestas, or treason; his execution is believed to have occurred shortly thereafter. By this time, Julia’s mother and brother, Agrippa Posthumus, were both living in exile. While Julia had reason enough to want to overthrow her grandfather, there is nothing to suggest that she played any part in her husband’s offenses.

Julia’s own disgrace was separate from her husband’s and did not transpire until two years later, in 8 CE. Harsh as it was exile was not her only punishment. In addition to Augustus razing her villa, Suetonius reports that Claudius ended his engagement to Aemilia Lepida, her daughter to whom he had previously been betrothed. Claudius, who would later become emperor, was Livia’s grandson and the brother of Germanicus. Suetonius states, “He put away the former before their marriage because her parents had offended Augustus,” highlighting that the annulment of the engagement stemmed not from Aemilia herself, but from her parents losing the emperor’s favor.

By having an affair with Decimus Junius Silanius, a prominent Roman senator from the Junii Silani family, Julia violated in a public and politically sensitive way the ever-unpopular Lex Iulia anti-adultery laws that Augustus had so assiduously chiseled into place. As an imperial woman, Julia was expected to serve as a role model and adhere to Augustus’s strict moral dictates, just as her mother had been expected to do before her harsh exile ten years before. In addition to wanting the princesses to serve as moral exemplars, Augustus also had deep insecurities about the success of his dynasty. The men in the imperial women’s social milieu all hailed from noble families; a popular princess who paired with any of them could have easily jeopardized the fragile foundation on which the house of Augustus lay. Regardless of the absence of conspiracy in her relationship with Silanus, any romantic liaison with a nobleman would have been unsettling to her paranoid and insecure grandfather.

Julia would never see her daughter again; she lost her home, her reputation, her newborn infant, and her very life. Meanwhile, although Silanus faced public disgrace, Augustus was satisfied that Silanus’s improprieties were moral rather than conspiratorial and did not formally prosecute him. Silanus retained his estates, chose voluntary exile and subsequently returned to Rome after Augustus’s death resuming full citizenship under Tiberius’s reign. The disparity in punishment between the two guilty parties raises questions. Some historians suggest that Silanus confessed everything to Augustus in an attempt to save himself, effectively leaving Julia to take the blame.

Even so, while Silanus’s situation may reflect broader societal attitudes toward gendered behavior, the Lex Iulia laws in themselves were patriarchal to their core. Despite the laws criminalizing adultery for both sexes, a married woman was guilty of adultery if she had sex with anyone except her husband while a married man was guilty of adultery if he had sex with a married woman. In other words, for married men single women, slave girls, prostitutes, and concubines were all up for grabs.

The primary concern of the laws was the assurance of paternity. Augustus implemented the anti-adultery laws to promote the procreation of legitimate offspring, especially among the elite, believing this would strengthen Rome’s dominance. Julia’s overt rejection of these laws may have sealed her fate. While her infidelity was a crime, an illegitimate pregnancy, was considered a capital offense.

Furthermore, this scandal brought shame and embarrassment to the ever-proud patriarch. Julia’s severe and public punishment illustrates the personal stakes involved and how far Augustus was willing to go to enforce his moral reforms. Like her mother before her, personal indignation and political imperative influenced Augustus’s actions. The blatant defiance of the laws by his daughter and granddaughter threatened the authority and prestige of the imperial dynasty. Augustus saw to it that even in her disgrace Julia would serve as an exemplar; her story (and that of her mother) functioned as a cautionary tale for others about the severe consequences of opposing the emperor’s vision for a virtuous society.

Nevertheless it should be noted that the moralizing marriage laws were proscribed by a man whose marital record was itself deeply tainted. While Augutus’s scandalous courtship of Livia was common knowledge and would have banished them both onto separate islands if the stringent laws had been in place during their courtship, Augustus’s indiscretions did not end with their marriage. Notorious for seducing the wives of his adversaries, Suetonius claims that Augustus’s friends rationalized his adulteries by saying he was motivated by politics rather than passion; his friends felt the the affairs were good for the Roman state: “That he was an adulterer upon many occasions even his friends did not deny.” In Life of Augustus, Suetonius– who wrote over one hundred years after Augustus’s death— highlights the hypocrisy between Augustus’s harsh moral legislation and his own personal violations of it.

Although the pre-eminent Roman poet Ovid was not banished due to his personal violation of the Lex Iulia laws, his and Julia’s exile in 8 CE by edict from Augustus has long led ancient and modern historians alike to suggest a connection between their downfalls. The poet himself attributes his exile to “a poem and a blunder” (carmen et error). The poem that put Ovid in Augustus’s line of aim is Ars Amatoria, which pokes fun at the emperor’s initiative to reinstate old Roman values and impose social and sexual discipline via legislation. The Ars Amatoria is a didactic poem instructing men on the art of seduction, particularly the pursuit of extramarital affairs—conduct that Augustus sought to curtail through his Lex Iulia laws. Ars Amatoria was perceived as subversive to Augustus’s official agenda of moral reforms because it both praised and taught about the sexual liberties that Augustus sought to suppress. Moreover, Ovid challenged imperial authority by setting romantic encounters against Augustan monuments.

The poem, however, was composed in 2 CE, six years prior to Ovid’s harsh exile. Although the poem was offensive to Augustus, Ovid claimed that the true reason for his exile was his “error,” which, while not illegal, was still significant. Today, most experts believe that Ovid’s error was not the act of committing adultery but rather witnessing it—specifically, the affair

Because Julia’s pregnancy long after her husband died was proof of her extramarital liaison, some historians posit that Ovid may have witnessed more than a mere indiscretion but rather a wedding between Julia and Silanus. Without the emperor’s consent, the marriage would have been nonbinding and illegal under Roman law and, in itself, a crime. Ovid never explicitly reveals the nature of this “error,” leaving it shrouded in mystery.

The irony is that, in many ways, Ovid endured a harsher punishment than Silanus, who committed the crime yet was allowed to return to Rome after Augustus’s death. Ovid implored his wife, family, and friends to seek a modification of his sentence, but their efforts were futile; as ever Augustus remained unyielding. Eight or nine years after his banishment, Ovid ultimately died while in exile in Tomis on the edge of the Roman Empire in today’s Romania.

As harsh as Augustus was to the preeminent poet, he was utterly barbaric to his eldest granddaughter. Like her mother before her, Julia had been trying to carve out a life of her own, but she was brought down by the very power that sought to control her. Stripped of the life she once had in Rome and devoid of all hopes and dreams, Julia must have been overwhelmed by unimaginable grief when, upon her infant’s birth, the baby was condemned to certain death. For twenty long years, she would be left to navigate a desolate existence, burdened by the weight of her sorrow and the unforgiving nature of her grandfather’s rule.

The Romans, who would never forget the mother’s harsh exile, were quick to forget her 27- year-old daughter, who shared the same cruel fate. Julia spent nearly half her life on the desolate prison island, passing away in 28 CE, shortly after the death of Livia. According to Tacitus, Livia had supported her step-granddaughter in her exile though she worked against her “while she flourished.” Following Livia’s death, Tiberius, who was now emperor, cut off all food supplies to Julia’s island outpost. At the age of 47, Julia died of starvation.