Long before her boat docked at the port of Brundisium in the winter of 19 CE, Agrippina (the Elder—14 BCE- 33 CE) might have known that the mourners would come out. Like the perfectly choreographed event many believe it was, people were packed on the waterfront elbow to elbow, some standing for days others for hours; they lined the city walls, with the boldest of them perched onto unstable rooftops—all to catch a glimpse of her. Adored and admired—she was the Roman darling. “The glory of a nation, they called her, the lone survivor of Augustus’ bloodline” writes Tacitus in his Annals. Agrippina was the daughter of Augustus’s (63 BCE-14 CE) only biological child, Julia, who had died in exile when Agrippina was a mere twelve years old. Although she once had four siblings, Agrippina, was considered the sole biological grandchild of the Divine Augustus—Augustus was so popular as emperor that upon his death he was deified. Her brothers were all dead at or before the tender age of twenty-five and her only sister, Julia, was in punitive exile from which she would never return. But on this day, Agrippina was more than just the progeny of a god; one half the golden couple, she was also the newly minted widow of Rome’s heir-apparent and one of the most celebrated of her generals—Germanicus Julius Caesar (15 BCE-19 CE). Biological nephew and adopted son of the ever-unpopular Emperor Tiberius (42 BCE-37 CE), Germanicus, was the hope of a nation and scion of the Julio-Claudian dynasty whose charisma off the battlefield and his multiple successes on it compared him to another beloved war-hero, Alexander the Great, who also died too young at thirty-three years of age.

The image of a grieving nation, an emaciated and pale Agrippina made her way across the gangplank with two of her six children in tow carrying the ashes from her freshly deceased husband when a collective wail descended from the crowd. Indistinguishable one from the other, men were crying, women were keening, strangers to Germanicus wept as fervently as his friends. In a boundless display of communal grief the people tore at their hair, pounded their chests, and howled for the world to hear—their golden prince was dead. But the mourning did not stop at Brundisium, it had only just begun. The tribunes and centurions of two praetorian cohorts greeted Agrippina lifting Germanicus’s urn onto their shoulders while the funeral procession marched across the Italian peninsula stopping at designated towns along the way. In a grand display of public bereavement grieving Romans dressed according to their station; plebeians wore black, knights dressed in vibrant purple and those in the upper stations wore dark togas. Coming from far and wide to pay respects to their fallen prince, the mourners streamed into the streets advancing their way to Rome where they were met by consuls and senators as well as Germanicus’s family members. Tiberius’s son, Drusus (14 BCE-23 CE), and Germanicus’s brother, Claudius (10 BCE-54 CE), and the rest of Agrippina’s and Germanicus’s six children took part in the nationwide funeral. But for all the solemn pomp and circumstance of Germanicus’s most public of funerals, one luminary was conspicuous in his absence, Germanicus’s biological uncle and adopted father: the Emperor Tiberius or as he preferred to be called the Princeps (first citizen). It was no secret that the relationship between the two men of contrasting dispositions was oftentimes strained.

……………………………

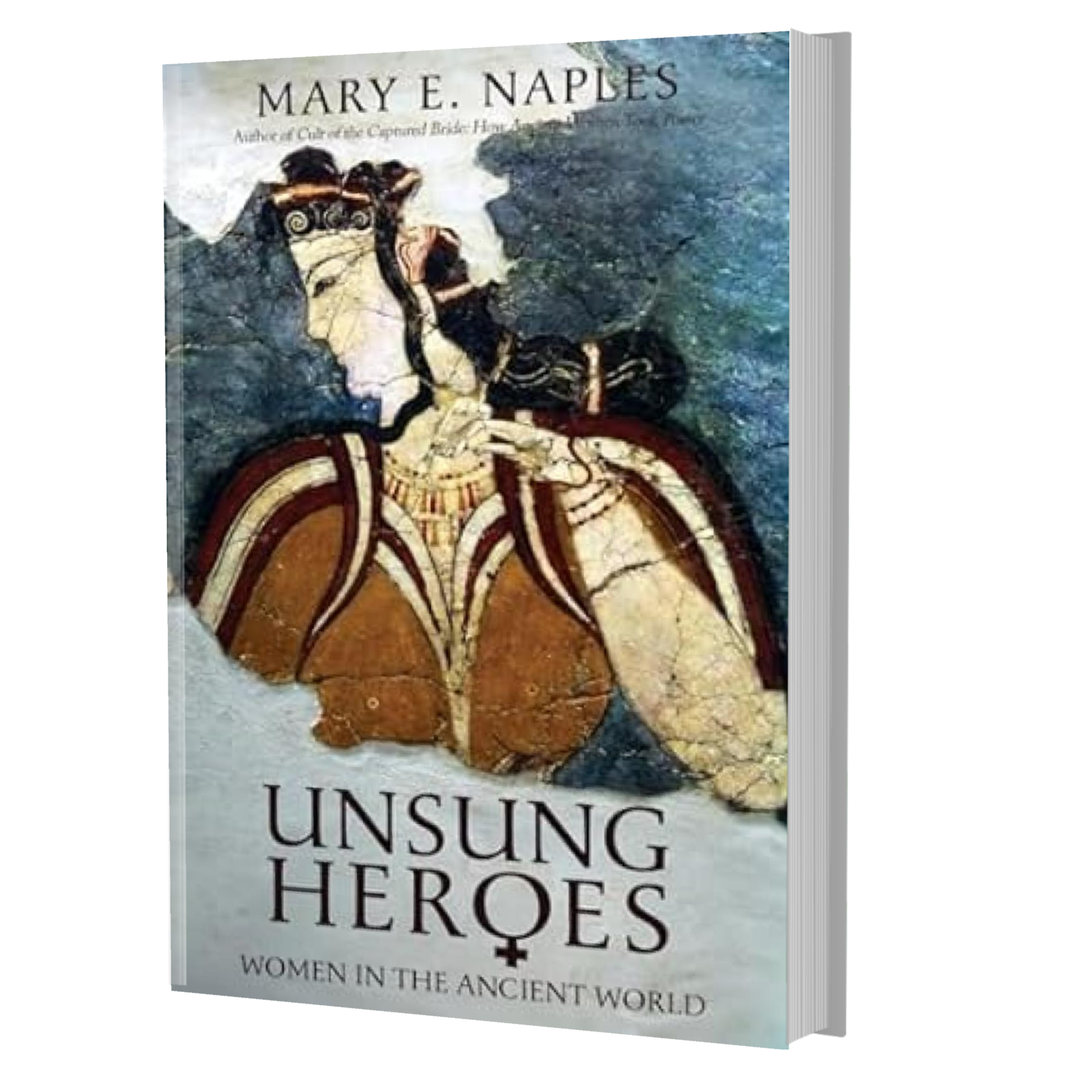

Why did Emperor Tiberius fear Agrippina “the sole biological grandchild of ‘Divine’ Augustus? Find out in my book Unsung Heroes on Amazon.