The playwright Sophocles (497 – 405 BCE) might have been amused to find that nearly twenty-five hundred years after writing about his eponymous heroine, the long-suffering Antigone is still making her resolute voice heard. While she cannot compare to her dear old dad-brother—Oedipus—-whose pathology is nothing short of institutional, the truth is that Antigone has been in analysis for at least as long as there has been analysis. Perhaps because she was progeny of an incestuous union, Antigone’s head has been examined by some of the finest minds; from psychotherapists to political theorists, poets and philosophers alike expound about her constancy while exploring the myriad motivations and mindset of this most complicated of characters.

The founder of psychoanalysis himself—- Sigmund Freud—believed Antigone was the product of primitive unconscious drives. The modernist author Virginia Woolf praised her as an “exemplar of heroism itself,” comparing her to the fearless suffragist, Emmeline Pankhurst. Most recently, American philosopher and gender theorist, Judith Butler, submits that Antigone portrays a dangerous form of feminism. While experts may have tried to find common ground, in the end, there are as many theories about Antigone as there are theorists. As a result, she has been burdened with a wide range of labels: from matriarchist to anarchist, yet for all that has been written about her, who is Antigone, and what makes her one of the most intriguing of patients?

To begin to understand the psyche of Antigone, it is important to get a grasp from whence she came. Because mythology was ubiquitous to the ancient Greeks, the audience would have been all too familiar with Oedipus’s woeful tale and the cursed Laius family. Frequently performed in mythological sequence, Sophocles’ Theban saga—-Oedipus the King, Oedipus at Colonus, and Antigone—- was written out of sequence and therefore not considered a trilogy in the manner of Aeschylus’ Oresteia. Each play of the Theban saga is a unit unto itself. Although the events in Antigone come last in the saga, in actuality, Sophocles wrote Antigone first (in about 442 BCE), preceding Oedipus the King by about twelve years. Thus, the Creon in Antigone has an altogether different persona than the Creon in Oedipus the King.

……………………………

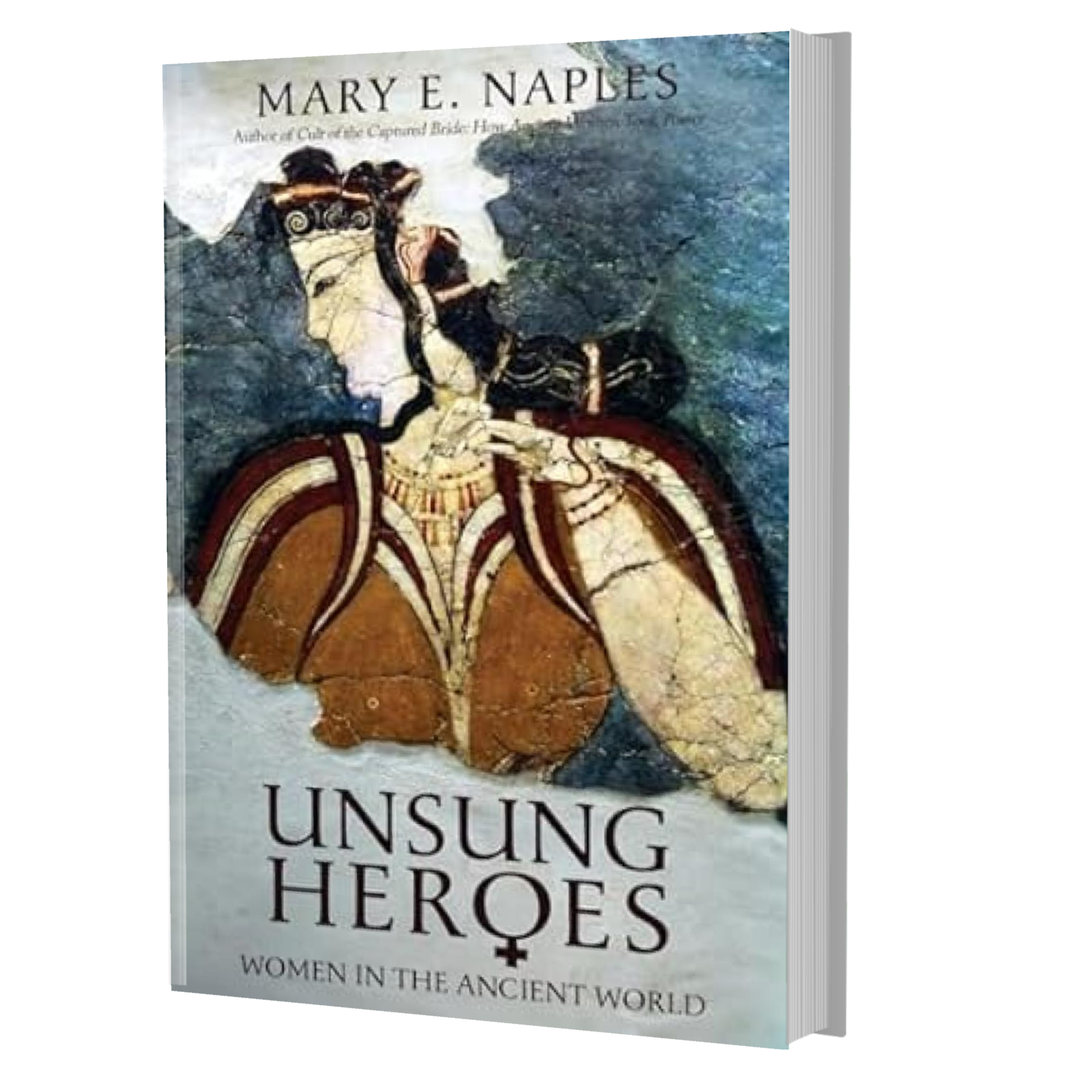

Anarchist or Matriarchist? What drove Antigone? Find out in my book Unsung Heroes on Amazon.