At long last, Tiberius was dead. After twenty-three long years marked by fear, mistrust, and paranoia, the grim and utterly unlikable Emperor Tiberius met his end at the advanced age of 78—a milestone that many of his victims would have envied. He was so beloved that Romans debated how best to desecrate his body, with some suggesting he should be hurled down the Gemonian steps (a fate reserved for common criminals) or pitched into the river. “Tiberius in the Tiberem” became a widely chanted slogan.

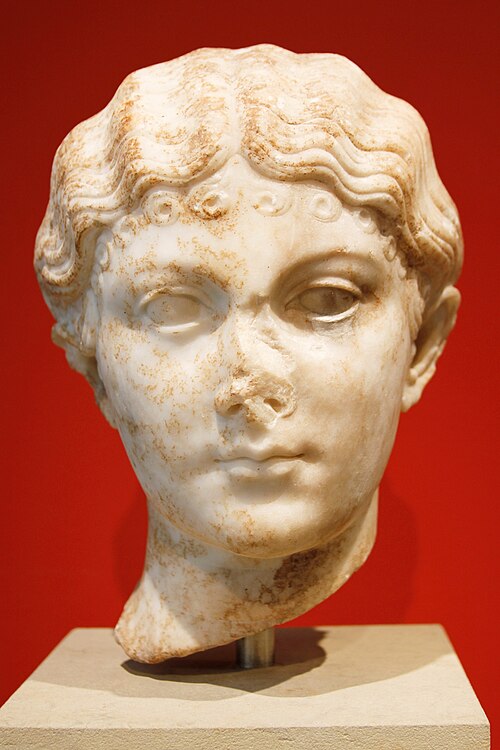

Within two days of Tiberius’s passing, the Senate officially confirmed his great-nephew, Gaius Julius Caesar Germanicus, as emperor. He is known to us as Caligula, or “Little Boots,” a nickname earned in childhood because of the miniature soldier’s boots (caligae) that his mother made him wear while accompanying his father on military campaigns. The Romans, however, always referred to him simply as Emperor Gaius.

The news spread quickly through the city streets, and soon all of Rome was drunk and riotous with delight. As crowds gathered to catch a glimpse of their twenty-four-year-old sovereign, the air was thick with excitement and anticipation. Although his golden family was in ruins—or perhaps because of it—the people turned out in droves for him. Suetonius reports that the celebrations welcoming Caligula’s rule were widespread throughout the empire and lasted for a full three months, featuring games, lavish public spectacles, and the sacrifices of more than 160,000 animals.

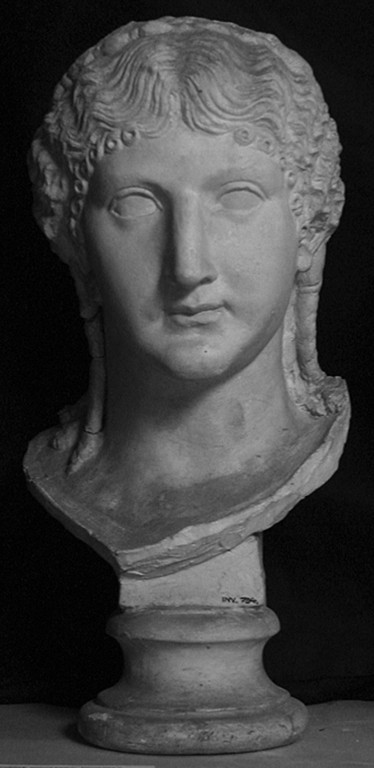

The crowds were not merely celebrating Tiberius’s death; more importantly, they were rejoicing in the return of their long-lost hero, Germanicus Julius Caesar, embodied in his only surviving son. But the charismatic war hero and former heir apparent, was only half of the golden couple; the throngs were also celebrating the return of his proud and strong-willed mother, Vipsania Agrippina, more widely known as Agrippina the Elder, the granddaughter of the “Divine Augustus,” once hailed as “the glory of the nation.” Known as the golden couple, Germanicus and Agrippina, along with their two eldest sons, left this world prematurely—thanks to Tiberius, who was either responsible for or implicated in the deaths of all four. Despite Tiberius’s best efforts to thwart it, one of the golden couple’s sons ultimately succeeded him, after all.

In his first act as emperor, Caligula traveled to the windswept island of Pandateria (today’s Ventotene), the site of his mother’s and brother Nero’s imprisonment and execution. He personally exhumed their remains and brought them back to Rome with him. At midday, when the streets were crowded, the two urns were ceremoniously carried on litters to be interred in the Mausoleum of Augustus, alongside the remains of his other brother, Drusus. The observance was intended to resemble a triumph for the family of Germanicus.

While the honors bestowed upon the deceased members of his family were significant, the recognition given to the living family members was even more remarkable. The Senate conferred upon his grandmother, Antonia Minor, the title of Augusta, the same as that given to the illustrious Livia, wife of Augustus.

But no accolades were more numerous than those he bestowed upon his three sisters—Julia Agrippina (the Younger), Julia Drusilla, and Julia Livilla. In a remarkable series of honors for women in the imperial dynasty, his sisters became the first living women to be depicted and named on imperial Roman coins. They were also the first women whose names were included in public oaths of fealty alongside the emperor’s (“I will hold myself and my children no dearer than I do Gaius and his sisters”). As well, they were the first women to be honorary Vestal Virgins, and Drusilla, his favorite sister, was the first woman named in the emperor’s will as his heir. Furthermore, Drusilla was the first woman to be deified upon her passing. Although Caligula’s treatment of his sisters marked a groundbreaking shift in the roles and visibility of imperial women, it remains unclear whether their roles extended beyond ceremonial duties.

The much-beleaguered family was reunited once again with a brother who supported his sisters both privately and publicly. Yet, within two short years, their once-loving brother turned against his surviving sisters and his brother-in-law (and best friend) Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. He charged them with committing adultery and with conspiracy to overthrow him to place Lepidus on the throne, which led to the exile of his sisters to nearby islands and the execution of Lepidus. What went wrong? In a conspiracy known as the Plot of the Three Daggers, were his surviving siblings genuinely plotting against him, as Caligula claimed? An analysis of the motivations behind these claims, along with the political context surrounding the allegation, may shed light on whether these accusations were simply indicative of his growing paranoia or represented a genuine threat to his authority. This paper reviews a complicated period in antiquity, which has left the academic community divided.

It began so well. With the promise of reform, Caligula initially rescinded Tiberius’s unpopular policies. He abolished the harsh treason trials and released those exiled or imprisoned under Tiberius. Not only did he eliminate unpopular taxes, easing the burden for so many, but he also gave every Roman citizen 150 sesterces and heads of households twice that amount as gifts. He initiated building projects on the Palatine Hill and elsewhere to improve Rome’s infrastructure and organized lavish public games on a grand scale, which contributed to a three-month period of celebration known as a “Golden Age” of happiness and prosperity in Rome. His generosity and acts of reform helped gain Caligula widespread popularity.

A serious illness that arose seven months into Caligula’s reign would change everything. He was incapacitated for over a month due to what the ancients referred to as “brain sickness.” While it is likely that his condition was neurological, the specifics of his illness have remained a mystery through the ages, with modern theories ranging from epileptic psychosis to schizophrenia. Suetonius reports that shortly after his illness, Caligula displayed signs of mental instability, marked by erratic mood swings, brutality, paranoia, and, notably, incestuous ties to his sisters.

Known for his hyperbole, Suetonius wrote about eighty years after Caligula’s reign in his work, Lives of the Twelve Caesars. He claims, “With all his sisters, he lived incestuously…” Similarly, in the second century CE, Tacitus discusses the incest accusations against Caligula in his work, Annals, but he presents them as rumors rather than facts. Finally, nearly two hundred years after Caligula’s reign, Cassius Dio, in Roman History, reports that the incestuous relationship involved only his favored sister, Drusilla. Thanks to the writings of these three primary Roman ancient chroniclers, the accounts of Caligula engaging in incestuous relations with his sister or sisters have persisted for nearly two millennia. But are these claims true? Incest, especially involving parents or siblings, was as taboo in the ancient world as it is today. However, such prohibitions did not stop the ancients from leveling incest accusations against public figures. These accusations often served as a common form of invective, aimed at undermining a figure’s credibility, since they could not be definitively proven or disproven.

Seneca, a Stoic philosopher and politician who received a death sentence from Caligula, and Philo of Alexandria, a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher, were two contemporaries of Caligula known for their sharp criticisms of him. But neither mentioned the incest allegations in their writings. This notable silence from these critics has led many modern scholars to believe that the incest claims were an exaggerated narrative introduced by later historians who were aligned with emperors hostile to the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

Nevertheless, excessive mourning for his sister, Drusilla, may have sparked speculation about incestuous ties. At just twenty-two years old, the death of Drusilla—who succumbed to an epidemic in Rome in 38 CE—deepened Caligula’s instability. Following her illness and death, Caligula’s behavior became increasingly erratic as he tried to fill the void left by Drusilla’s absence with grand displays of authority. Overwhelmed by grief, he not only stayed by her side during her illness but also ensured after her death that she received a burial befitting an Augusta. He asked the Roman Senate to recognize her as a goddess conferring upon her the title “Panthea,” meaning “universal goddess” and in her honor, he consecrated a temple. According to Suetonius, as an expression of profound grief, he fled the city to Syracuse without shaving his hair or cutting his beard: “and never afterwards took an oath about matters of the highest moment, even before the assembly of the people or in the presence of the soldiers, except by the godhead of Drusilla.” Moreover, he instituted a mandatory mourning period for the Roman populace, during which any expressions of joy—including laughter, swimming, dining with family, or any form of personal pleasure—were punishable by death.

Despite all the conjecture over the years about their relations, Caligula had practical reasons for venerating his sisters. He was a widower when he ascended to the throne and remained unmarried throughout his protracted illness. Due to the absence of a wife and heir, Caligula relied on his married sisters to propagate the dynasty. Their elevated status highlights that, within the Julio-Claudian dynasty, women held political significance as conveyers of the imperial family. Although no woman could ascend to the throne, during his illness, Caligula named Drusilla as his successor nonetheless; no woman in ancient Rome, before or after, had ever been designated as an imperial heir.

Since Drusilla predeceased Caligula, however, her succession would never materialize. Most historians believe he chose Drusilla to ensure that Lepidus— Drusilla’s husband—would assume power until she bore a male heir. Following Drusilla’s death, many viewed Lepidus as Caligula’s potential successor. If Lepidus were the son of Julia the Younger (Agrippina the Elder’s disgraced sister) as some scholars suggest, he would have been a Julio-Augustan by birth as well as by marriage with even more claim to the throne.

While Lepidus’s ambitions for the throne were predictable, why would Agrippina and Livilla attempt a coup when their brother had already elevated them to positions of significant power? Caligula’s fourth and final marriage to Milonia Caesonia in early to mid-39 may have provided a chasm between the emperor and his closest relations, which was further breached upon the birth of Caligula’s heir—a daughter, Julia Drusilla. With his sister Drusilla no longer in the line of immediate succession, the conspirators may have turned their attention to their personal interests. Moreover, likely they were also concerned that Caligula was losing control and becoming vulnerable to a coup from outside the dynasty.

After two years in power, Caligula’s relationship with the Senate had significantly deteriorated. Both Suetonius and Dio recount that some time before the failed coup, Caligula admonished the Senate for its previous inconsistency in honoring Tiberius and his ally Sejanus and then reversing its stance by denouncing Sejanus and, after his death, Tiberius. Caligula asserted that any praise they might offer him could similarly be insincere and hide their true animosity toward him. In his address, he labeled all senators as “clients of Sejanus” and “informers against his mother and siblings.” He is thought to have concluded the speech with the infamous remark, “Let them hate me, provided they fear me.”

To keep his perceived enemies at bay, he reinstated maiestas, or treason trials, which had become notorious during Tiberius’s reign. In an effort to replenish the treasury, which his lavish spending had drained, he targeted numerous senators and other aristocrats in these trials to confiscate their assets. The unjust proceedings resulted in many facing execution or choosing suicide. Exhibiting increasingly erratic behavior, Caligula began to rule as an absolute and dictatorial emperor.which caused considerable alarm among the Senate and the aristocracy as a whole, including those within his inner circle.

The conspiracy known as the Plot of the Three Daggers was extensive, involving Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Gaetulicus, the commander of Upper Germania, along with military support and considerable backing from various members of the Senate and the aristocracy at large. The stage was set; all that remained was the assassination of Caligula. However, someone alerted the emperor about the plot, making him aware of the conspiracy well before it could be executed. Despite his unstable personality, Caligula meticulously crafted a successful counter-strategy. In a surprising move, he marched his troops to Gaul/Germany, catching Gaetulicus off guard. Without the chance to prepare his legions for open rebellion, Gaetulicus was ambushed. In a desperate bid for self-preservation, he likely betrayed his fellow co-conspirators, revealing the broader aspects of the conspiracy. Yet, his attempt was all in vain, as he was executed regardless.

At Lepidus’s causa (hearing), Caligula made public incriminating letters (according to Suetonius, obtained “by deception and debauchery”) written by Agrippina and Livilla indicating that they had committed adultery with Lepidus and were plotting to overthrow their brother. In Julio-Claudian Rome, allegations of adultery against influential women often amounted to accusations of treason. Similar to Caligula’s sisters, spurious adultery charges made by paranoid emperors—when the real concern was threat of treason—led many of their female antecedents into exile. Worth noting, to illustrate their lack of awareness regarding the plot, Agrippina’s husband, Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, and Livilla’s husband, Marcus Vinicius, appeared unaffected by the accusations directed at their wives.

Often depicted as “overly” ambitious by both ancient and modern historians alike—a critique not directed at her male counterparts—Tacitus recounts the reason for Agrippina’s adulterous affair with Lepidus as being “in the hope of power.” By then, Agrippina’s son Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, who would later become Emperor Nero, had been born. With Drusilla gone and her elderly husband in declining health, Agrippina might have been aiming for greater things than the significant advantages of being Caligula’s esteemed sister. Marrying an Emperor Lepidus would have not only made her an empress but also, at the same time, set her son up as heir to the throne. But if Agrippina was to be the next empress, what did Livilla stand to gain? Aside from wanting her cruel and likely perverted brother out of the picture, why would she be in on the plot?

As with many details surrounding the conspiracy, including the trial’s location, the sources remain unclear. Among the three Roman chroniclers, Tacitus provides the most detailed accounts of the Julio-Claudian dynasty; however, the chapter on Caligula in his Annals is lost, resulting in significant gaps in our understanding of Caligula’s reign.

Some scholars argue that it was Caligula’s fevered paranoia, rather than a genuine threat to his rule, that drove the exaggerated allegations against his sisters. The sources are consistent in calling the charges against the sisters “allegations,” not crimes. It would not be the first (nor the last) time an emperor exiled female relatives for becoming too close to the centers of power. Furthermore, while he threatened them mercilessly during their exile, he did not execute them, suggesting either a lesser offense or that the evidence against them was insufficient to warrant the death penalty, although sufficient evidence was rarely a prerequisite for execution in Caligula’s Rome.

Lepidus, however, was not as fortunate as Caligula’s sisters. He was found guilty as an accessory to the plot to assassinate Caligula and was executed shortly thereafter. To commemorate Lepidus’s death, Caligula sent three daggers—symbolizing the three swords his sisters and Lepidus would have used to assassinate him—to the Temple of Mars Ultor in Rome. This act served as a dramatic denouement that might give his enemies pause. Mars Ultor, a prominent Roman god, symbolized vengeance, particularly in addressing wrongs committed against Rome or its leaders. In 2 BCE, Augustus dedicated a temple to Mars Ultor as the divine agent of vengeance for the assassination of Julius Caesar.

In another instance of theatrical parody, Caligula mockingly referenced his mother’s celebrated journey from Antioch (today’s Antakya in southern Turkey) to Rome, during which she carried the ashes of Germanicus. Ever cruel, he commanded a humiliated Agrippina to transport an urn containing the bones of Lepidus back to Rome. The event likely posed a significant security challenge, as the procession would have lasted for days and included numerous participants as well as hordes of onlookers. Upon Agrippina’s arrival in Rome, the Senate decreed that Lepidus’s bones should be cast out unburied rather than interred in the customary columbarium.

Also found guilty as accessories to the conspiracy, the sisters were banished to separate islands, each sent to one of the two Pontine Islands (today’s Ponza and Ventotene). The hypocrisy was not lost on anyone as just two years earlier, he had made a grand public gesture by retrieving the remains of his unfortunate mother and brother from these same prison islands, where the ruthless Tiberius had confined then executed them. It was now his turn to take on the role of brutal dictator.

Once his sisters were banished, he would frequently display his notorious cruelty by threatening them with messages such that he had “swords as well as islands at his disposal.” Later on, in an attempt to mitigate the extravagant expenses that helped make his reign infamous, he auctioned off his sisters’ possessions, including their jewelry, furniture, slaves, and freedmen, all at inflated prices, thus impoverishing them and enriching himself in the process.

In 41 CE, just two years later, they would outlive their brother’s brutal dictatorship and be released from their prison islands when, at the age of twenty-eight, he was fatally stabbed multiple times as he left a public event. The attack was orchestrated by a conspiracy involving officers from the Praetorian Guard, courtiers, and senators. Shortly after his assassination, his wife and daughter were murdered to eliminate any potential claim to the throne. In a surprise move, his uncle, Claudius—who was largely dismissed as a serious contender for the throne due to his poor health—was swiftly proclaimed the new emperor by the Praetorian Guard.

His sisters, however, had disparate fortunes. Almost as soon as her Uncle Claudius recalled Livilla from exile, he exiled her again, accusing her of adultery. As with many accusations of this nature, the charges were baseless. This time, she was implicated alongside the famed philosopher Seneca, who was also sent into exile. However, unlike Livilla, Seneca survived his banishment and lived to tell the tale. Although Claudius ordered Livilla’s execution, the ancients blame his jealous wife, Messalina, for her fate. They say it was due to Livilla’s remarkable beauty and the fear of her influence that, in late 41 or early 42, Messalina persuaded Claudius to order her execution. At the age of twenty-four, she was starved to death.

The gods had other plans for her sister. A driving force behind her emperor husband and emperor son, Agrippina’s name would become a byword for a woman of formidable determination. Her first husband died when she was in exile, but upon her release she would marry twice again, with her final marriage being to Emperor Claudius himself, her uncle. Marriage between an uncle and niece was considered incestuous by Roman law, so the Senate convened to authorize the marriage between Claudius and his niece Agrippina. A special dispensation was made because he was her father’s brother, not her mother’s. The marriage, however, benefited them both. In an attempt to secure his position on the throne, Claudius was marrying a descendant of the “Divine Augustus” and the daughter of the celebrated General Germanicus. For her part, at long last Agrippina was made empress, while securing a pathway to the throne for her son, Nero, who would succeed Claudius and ultimately bring a dramatic conclusion to the ninety-five-year Julio-Claudian Dynasty.