The streets of Rome were drunk and riotous with delight in the summer of 29 BCE on the final, most opulent day of Octavian’s three-day-long triumph celebrating his victory over Egypt’s Cleopatra. Always up for a party, hundreds of thousands of spectators—–some of whom had been standing for days, others for hours—were packed side by side as they lined the city walls to catch a glimpse of the three-mile-long procession winding its way through the capitol. As the clamorous procession rolled by Rome’s mud and brick buildings, the cobblestone streets were awash with the shimmering splendor of gold, silver, and ivory—-swaggering plunder from Egypt’s enormous reserves.

Spurred on by each other and goaded by the wine, the main exhibit the crowd was craning their necks to see was coming up at the rear. Since Cleopatra’s suicide denied Rome the supreme satisfaction of seeing her in shackles, Octavian was reduced to parading around her likeness instead. Fully costumed in effigy, the queen the Romans loved to hate was in a death throes abreast her soon-to-be trademark asp. But a hush fell upon the jeering crowd when their focus was drawn to the two children manacled in chains of gold standing beside her. So that there was no question over whose children they were, Octavian made Alexander Helios (Sun) and Cleopatra Selene (Moon) dress as the sun and the moon. Though the two ten-year-old fraternal twins of Cleopatra and Marc Antony were no strangers to public display, their fall from grace is hard to imagine. A few years preceding in the largest structure of Alexandria—the expansive six-hundred-foot-long gymnasium—- the children, along with their parents and two brothers, were hailed as potentates and worshiped as gods.

That was when their parents summoned all of Alexandria to the marble-colonaded gymnasium for a lavish extravaganza known as the Donations of Alexandria. In the grand finale of the pageant, Antony and Cleopatra were seated on gigantic golden thrones and costumed as Dionysus/Osiris and Aphrodite/Isis. Cleopatra’s son by Julius Caesar—Ptolemy XV Caesar “Caesarion” —- was dressed as their son Horus. The twins, at six years of age, made their first public appearance similarly attired in elaborate costumes. More show than substance, the donations were a series of territorial “gifts” from Antony to Cleopatra. The territories, however, were either already within her domain or were under Roman control and fancifully within her reach.

……………………………

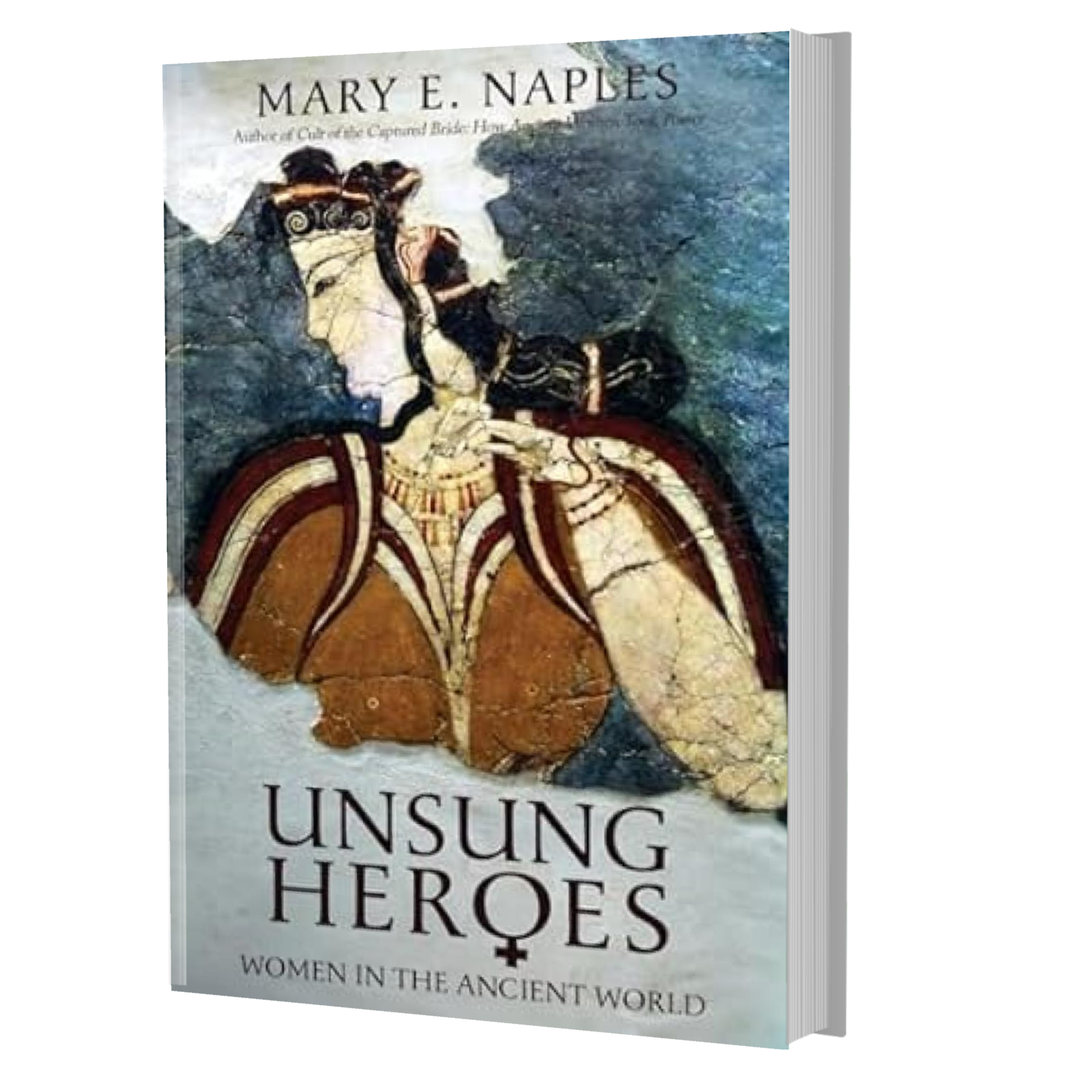

Interested in learning how Cleopatra Selene became one of the most powerful women in the Julio/Claudian dynasty? Read more about her in my book Unsung Heroes on Amazon.