Before she was a queen, she was a goddess. Born to the purple and weaned on pageantry, Cleopatra (69 BCE-30 BCE) was addressed as Thea (goddess) from birth. Implicit in the belief in the sanctity of the royal line, there was little distinction between monarchy and divinity for Egyptians. As a means of preserving it, sanctity was imbued within the monarchy itself. That is not to say that an unpopular pharaoh could not be ousted from time to time, yet the dynasty was left intact. Supplemental to being god-like, the pharaoh or king was also high priest and as such could communicate with other gods and the deceased; a profound differentiation from his subjects.

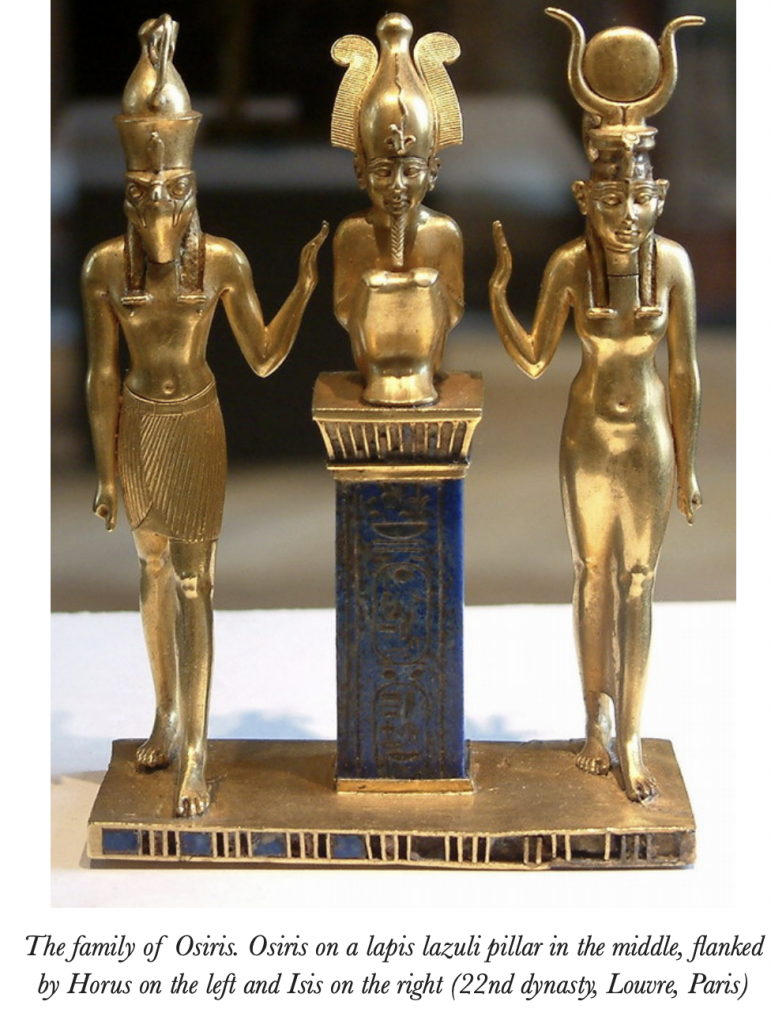

Forasmuch as the kings were the dominant ruler, the queens wielded considerable strength—sometimes eclipsing that of their husbands—by the power inherent in the goddesses, who oftentimes were more powerful than their male counterparts. It must be remembered that even in the Ptolemaic era (323 BCE-30 BCE), Egypt was an ancient kingdom whose deities sprang forth from the primordial mist. The most primal of them being that of the original mother goddess who endowed fertility on the region and whose beneficence was critical to its health and well-being. Therefore, honoring her with temples and pageantry was essential to her good graces. Largely illiterate, image was everything to the native Egyptians so playing the role of the goddess was tantamount to being one. Costumed in the full regalia of the deity with whom they identified, the goddess most represented by queens was Isis, the supreme mother goddess, who was both wife and sister to the predominant deity, Osiris and mother to Horus.

Isis, whose Egyptian name is Aset, began to appear in Egyptian texts as early as the Fifth Dynasty (2494 BCE-2345 BCE). As mother goddess, Isis was the chief character in the Osiris resurrection myth. As in many ancient myths, this one is both convoluted and begins with a fratricide. Osiris, the King of Egypt, attends a party hosted by his evil brother, Seth, who lures Osiris into a narrow chest then locks him within it and flings the chest into the Nile River. Isis is overcome with grief and over a period of years searches high and low for her husband. Finally, she finds his chest hidden within one of the pillars in the great palace of the King of Byblos (present Lebanon). A labyrinthine adventure ensues which culminates in Isis cutting the pillar to reveal the precious chest then taking it back with her to Egypt in order to bury Osiris in his homeland.

But Seth wasn’t done with disposing of his brother. Somehow, in the Egyptian desert he discovers Osiris lying in his coffin and hacks him into small pieces scattering them everywhere. With the help of Anubis, the jackal-headed god, Isis was able to recover all of Osiris’ body parts. All, that is, except for his penis, which, alas, the ever-greedy Nile fish consumed. Summoning her magical powers, Isis, equipped her husband with an imitation penis, then transformed herself into a bird and hovered over her husband’s prone body, breathing her brand of magic into his inert form. Lo and behold, nine months later she bore Osiris a son, Horus; and Osiris withdrew into immortality to become king of the dead. As a good mother and an astonishing goddess, she guarded Horus from his evil uncle until he was old enough to demand his legacy.

In the legend, Osiris, represents the eternity of deceased pharaohs while Horus symbolizes his successors; the living kings who rule Egypt. But it’s the agency of Isis which drives the story. The men in the story, if not outwardly evil like Seth, are relatively inert. After all, Osiris is dead for much of the myth and Horus isn’t born until the end of it. It is the powerful will of Isis along with her clever use of magical and healing powers which saved the day. Not only did she give birth to Horus, she all but sired him as well. And it was Isis who secured Horus’ legacy from the clutches of his evil Uncle Seth. Many scholars attribute the strong role that Isis played in the Egyptian pantheon to the relative freedom enjoyed by women in Egypt compared to their feminine counterparts in Greece and Rome.

Over the centuries, Isis, while still exhibiting her primary maternal traits began evolving into a more diverse goddess expressing a universality which made her alluring not only to native Egyptians but to Greeks and Romans as well by her close resemblance to Grecian Demeter and Roman Ceres. Though characteristically, the Romans were ambivalent about Isis; the people adored her on the one hand while the state was uneasy about her cult on the other. In the years 80 BCE, 58 BCE, 53 BCE, 50 BCE, 38 BCE and 19 CE, temples were built then torn down then raised back up again by popular demand. Even Julius Caesar (100 BCE-44 BCE)—a man more than a little familiar with Egyptian goddesses—forbid the priesthood of Isis from entering Rome. Yet despite this ambivalence on the part of the state, many Romans had Isis statuary in their household shrines and worshipped her alongside the Roman pantheon. Her cult symbol of a mother cradling her child became known throughout the Graeco-Roman world and was the prototype for the early Christian Madonna and child; an iconography that Cleopatra helped perpetuate as will be discussed a bit later in this article.

Even at fourteen years of age, as her father’s co-regent, Cleopatra emphasized associations between herself and Isis by incorporating the title Nea Isis or New Isis into her regal name. But after giving birth to Caesarion (Little Caesar—Ptolemy XV; 47 BCE-30 BCE), Cleopatra was transformed into Isis personified overnight. It must have seemed oddly synchronous to her that Isis’s story so closely mirrored her own. Both were single mothers of sons whose fathers met violent ends and were considered gods (after his assassination, Caesar was deified). Further, both Horus and Caesarion were heralded as sons of gods. Most Egyptians would have assumed that just as Cleopatra was the living Isis, as her mother’s son and male co-regent, Caesarion was the living Horus. His worldwide appeal would have seemed inevitable given his divine parentage. The son of god in an age desperately looking for a savior. Caesarion symbolically linked east and west personifying a vision of world peace through global unification which was the ultimate dream not only of his mother but of their forebear, Alexander the Great (356 BCE-323 BCE) as well. Yet as important a role as Caesarion’s divinity played in Cleopatra’s narrative, hers was even more so.

Trumpeted as a deity from birth, is it possible that Cleopatra truly believed she was Isis? One thing is certain, she used metaphor and theatrics to her advantage. After Caesarion’s birth, coins were issued featuring Cleopatra wearing the Isis diadem on one side and the image of Caesarion at his mother’s breast on the other; a pose identical to the iconic pose of Isis and her suckling Horus. At public events, Cleopatra played the part convincingly. Adorned in the ceremonial robes of Isis, donning a tripartite wig and vulture headdress with eyes outlined in black kohl and green malachite, she was the splitting image of the goddess. With little difference between the mortal queen and the eternal goddess, her pious subjects would have been reluctant to go against the queen’s edicts. While we can never know if her liturgical pageantry was devotional, politically expedient or a combination of both, what we do know is that Cleopatra was a more than capable leader.

She transformed Egypt from the weak client-state she inherited from her father into a force to be reckoned with on the global stage, second only in power and influence to the Roman Empire. In her twenty-one-year reign Cleopatra expanded the Egyptian empire not only to its size at the time of her exemplar, Alexander the Great, but to its size at the height of Egypt’s power one thousand years earlier. Yet it was Egypt’s growing influence along with her on-going relationship to Marc Antony (83 BCE- 30 BCE), that put Cleopatra in Rome’s crosshairs.

In a contest pitting a cold-blooded upstart against a general not only beloved by his troops but supported by Egypt’s sizable war chest, the odds were clearly in the latter’s favor—until the Battle of Actium. Hardly the decisive victory of which Octavian (27 BCE- 14 CE) propagandized, yet once the power couple lost their footing they never regained dominance. After their defeat, Cleopatra packed Caesarion off; as her co-regent and the biological son of Caesar she knew his life was in grave danger. Plutarch claims that Cleopatra sent Caesarion to India but that after her death Octavian lured the sixteen-year-old Casearion back to Alexandria where he had the youth quickly dispatched. Ever the pragmatist, Octavian had been touting himself as the adopted son of the divine Caesar hence “the son of god”—a term that would become quotidian. The mere existence of Caesarion, the true son of Caesar or god was a direct threat to Octavian’s leadership. Alas, there was only room for one son of god in the Roman Empire.

Characteristically, Cleopatra chose suicide over being paraded through the streets of Rome as part of Octavian’s Triumph. But even in death, Cleopatra was worshipped. Egyptians formed a cult on her behalf with iconography that comingled with that of the Isis religion making it impossible to tell one from the other. Because he forbade all things Egyptian in the public square during his reign, after Augustus’ (Octavian) death (14 CE) the cult symbol of the Cleopatra-Isis mother and child was soon enthusiastically embraced by the Romans. Ironically although defeated by the Roman Empire, Cleopatra endures in the mother and child iconography that would eventually be adopted by the rival Christian cult for their Madonna and child imagery that continues to this day.

Ultimately, the worship of Isis in Rome continued well into the advent of Christianity, until Emperor Theodosius I issued a decree to shutter all pagan temples in 380 CE. At around this same time in 373 CE, at an Isis temple complex on the Egyptian island of Philae, the following inscription was found on a statue of the goddess queen: “Overlaid the wooden figure of Cleopatra the god.” This brief scrawl indicates that the cult of Cleopatra was still active until at least the 4th century CE. But is it possible that her religion continued beyond that date? In what is considered to be the grand finale of the Egyptian religion: the Cleopatra/Isis temple at Philae was forcefully closed in the 6th century CE by Byzantine emperor Justinian the Great (527 CE-565 CE). Closure by imperial edict suggests the temple’s viability until that point in time; over 500 years after her death Egyptians were still venerating their goddess queen. Celebrated as a goddess in life, and worshiped as one in death, Cleopatra achieved a level of immortality that remains to this day. In legend, literature and art, she is an icon that is as emblematic as the Madonna and child symbol which her worship helped propagate.

Published on Classical Wisdom