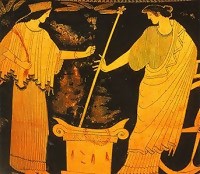

In the indigo light of the early morning, wearing white robes and carrying torches, the pious women ascended the hill to the Thesmophorion (sanctuary to Demeter) in observance of their three day long annual festival honoring Demeter, goddess of the harvest, and her daughter Persephone.

Were they chanting? Were they singing? We can only guess. They must have numbered in the hundreds, perhaps thousands—a procession—exalting to behold.

Considered the oldest and most widespread of all religious festivals in ancient Greece, the Thesmophoria was a feminine-only fertility cult whose celebrations spanned from Sicily in the west to Asia Minor (present day Turkey) in the east and everywhere in between. Most scholars maintain that its ubiquity in the Greek world was testament to its primeval origins. Established, organized and engaged in by women, membership in the Thesmophoria was restricted to citizen wives in good standing; no maidens or female slaves were allowed.

Though strictly prohibited from attending the event—sometimes to the point of death—men, that is to say male citizens, were still responsible for the expenses related to its celebration.

Because of its deep cultural significance, on the second day of the Thesmophoria, all law courts and council meetings in the polis were suspended. Additionally all prisoners were released from jail. Women then celebrated the Thesmophoria away from their homes and families for a minimum of three days and nights. Ironically, although women’s place was on the margins of hyper-patriarchal ancient Greece, the Thesmophoria was given prominence in greater society.

In order to understand the importance the Thesmophoria may have had in women’s lives, it is vital to discuss the role Demeter and her daughter Persephone play in the myth as their narrative has relevance in the feminine festival.

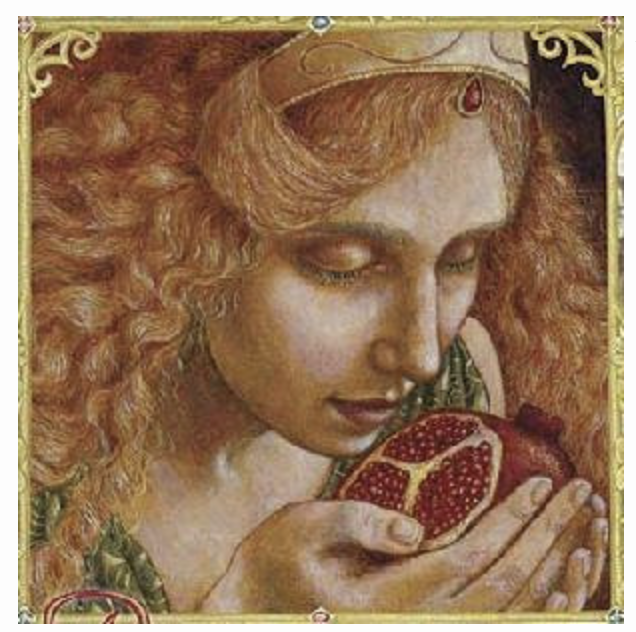

The story begins with an arrangement between Zeus—lord of the gods and his brother Hades—lord of the underworld, to kidnap Persephone and make her queen of Hades’ dark domain. Ignorant of their unholy alliance and in an effort to win her daughter back from the land of the dead, Demeter stops the seasons turning the earth into a barren wasteland. Although Zeus pleads with her to make the earth abundant once again, Demeter refuses to relent until Persephone is restored to the light of her earthly domain. Ultimately, Zeus acquiesces to Demeter’s demands and orders Hades to release Persephone. But before Hades adheres, he lures Persephone into eating a pomegranate seed.

The mere act of eating in the underworld, keeps Persephone as his wife in his domain for a few months each year.

At its most fundamental level, the Thesmophoria celebrated Persephone’s journey from her descent into the underworld to her resurrection and life on earth. At a symbolic level relating to agriculture, Persephone is a metaphor for the seed, which in the Mediterranean region goes underground or lies dormant in the summer months only to be released again for planting in autumn.

While we may never know how the citizen wives practiced their secret ritual, literary and archaeological evidence suggests that in one of their integral rites, citizen wives handled death in order to bring forth life.

How did the women embark on this critical undertaking? Previous to the festival, the members had elected two prominent women called bailers or anteltriai who were tasked with descending the deep hollow of the cavern or megara to remove its “sacred objects.” Because it was understood to represent the womb of Demeter, the cavern was a common chamber within the Thesmophorion.

The “sacred objects” were comprised of rotted piglets along with other objects believed to increase fertility such as dough cakes in the shape of male and female genitalia as well as fir cones.

Because of its fecundity, the pig was associated with Demeter. Likewise fir cones were used because pine trees were known to be prolific.

This newly born humus the bailers scoop up is symbolic of the power the citizen wives possess. Through Demeter, they are able to generate life in an exclusively feminine cycle. The “sacred objects” were then placed on the altars of the two goddesses and mixed with seed constituting what may be one of the first examples of composting. Plentiful humus was a favorable portent, indicating the goddesses delight at the festival and insuring the strength of the seeds in the forthcoming sowing season.

While we envision ancient Greece as being the seat of Western civilization, for all its sophistication, it was still chiefly an agrarian society where most of its residents worked the land. But because the land tended to be non-arable, the Greeks found it necessary to have several fertility festivals throughout the year as a means of appeasing the gods and garnering control in order to encourage fertility.

And due to their ever-expanding empire, they needed an ample supply of men to maintain their military commitments, as well as women to produce the much-coveted male citizens.

As such, Demeter was the chief fertility deity who was honored for her role in both crop and human fertility, aiding the Ancient Greeks in increasing the wealth in their world.

Ultimately, the work of the citizen wives was done. Filing out processionally, the pious women descended from the Thesmophorion. Spectators lined the streets in order to watch them make their descent from the sanctuary. After all, they played a critical role as the health and prosperity of the polis rested on their shoulders.

Read the original publishing at Classical Wisdom