The hooded gaze of an inscrutable Theodora (c.497- 548 CE) greets hundreds of thousands of visitors each year as they pay their respects to her mosaic at the Basilica of Saint Vitale in Ravenna, Italy. Encircled in glittering gold and bedecked in crown jewels, her visage befits the powerful Byzantine Roman empress she once was. More partner than figurehead, Theodora is considered to have been one of the most powerful and influential of all empresses. Yet while her image on the mosaic is discernible, due to the incoherent misogynist and classist ramblings of an ancient chronicler the image she presents to history is somewhat less so. Alas, much of what we know about Theodora comes from the poisonous pen of Procopius of Caesarea—–primary Justinian (483 – 565 CE) historian. Prior to Anecdota or Secret History, Procopius had written nothing but praise about the Justinian administration, so the book came as something of a surprise to the academic community when it was re-discovered centuries after it was written in 550 CE. Brimming with hyperbole and invective against the royal couple whom Procopius characterizes as “demons,” Secret History, at times, reads like the tabloid press. No character, however, is more impugned than that of the empress. Like all ancient chroniclers when reporting about powerful women, Procopius focuses on her sexuality. He repeatedly refers to the time—-when as a child and young adult—-she performed on stage and engaged in the oldest of professions. But according to Procopius, licentiousness was not her only sin, she was also cruel, spiteful, vindictive, and tyrannical. Regrettably, Procopius’s fiery invective against Theodora has influenced subsequent historians who have let his slander cloud their judgment on this complicated empress.

Notwithstanding, Procopius’s poison pen, who was Empress Theodora? While her work in the sex trade is unconfirmed, her humble origins are not. In an era not known for social mobility, how did the daughter of a bear keeper rise to the highest office in the land? And why was her reign in many ways more remarkable than that of her husband, Justinian?

Her father’s death when she was five left her family in desperate need. Although her mother quickly remarried, when the bear keeper post vacated by her late husband was denied to her new husband, the family remained financially in the lurch. Because employment options were few and far between for females of any age in sixth-century Constantinople, Theodora’s mother had to be resourceful—a trait Theodora must have inherited. She encouraged her three daughters to perform on stage as mime actresses. Yet, in the minds of Byzantine society, there was a stigma attached to acting. Because its focus was on the “sins of the flesh” — theater was considered the quintessence of depravity.

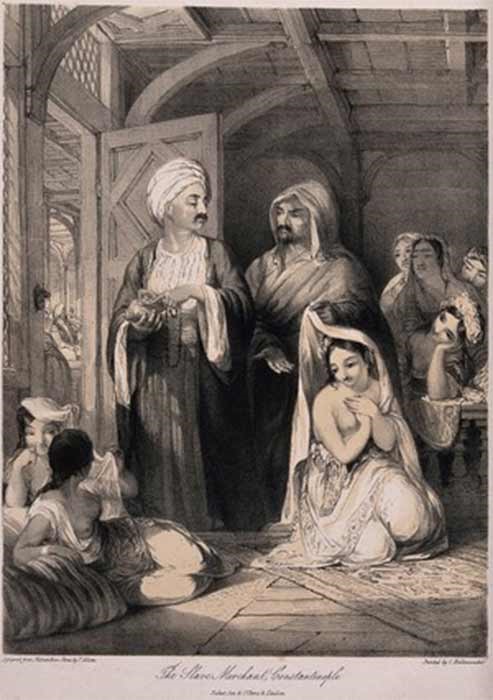

To be sure, there was little difference between actresses and prostitutes, and both were outcasts from society. When she reached “maturity”—likely at the tender age of twelve—Theodora officially began her acting career. Although his account may be less than reliable, Procopius casts aspersions on the tender-aged Theodora for playing the role of victim when he claims that once she reached puberty “and at last was ripe for it, she joined the women on stage and promptly became a prostitute.” Procopius, however, could only know about her work as a prostitute by hearsay since he himself was a child at the time. Be that as it may, with her quick wit, good looks, and precocity, she soon achieved notoriety as a comic actress, capturing the attention of men of means.

Eventually, she moved out of Constantinople to become the live-in mistress of a wealthy governor (Hecebolus) in Libya. By some reports, Theodora may have even had one or two children by then—though accounts of them are scant. Sometime after the relationship with the governor soured, Theodora, on her way back to Constantinople stopped first in Alexandria, then in Antioch. Many scholars believe it was while she was in Alexandria that she underwent a full religious conversion that not only changed the course of her life but may have changed the course of religious belief in the region as well. Her adopted religion, a branch of early Christianity called Monophysitism argued that Christ had only a divine nature. This belief was at odds with most of the West and the Byzantine state itself which believed that Christ had two natures—both fully human and fully divine. The impact of her religious fervor will be covered later in this paper.

In a move that may seem contrary to religious belief it has been suggested that while living abroad and with easy access to circles of influence, the forthcoming empress may have been a Byzantine spy condemning noblemen from the East. After all, state governments have long been known to use actresses or prostitutes in intelligence gathering operations. Rumors that Theodora became a wool spinner during this time appear to be unfounded and belong instead to another Empress Theodora who lived in the ninth century. Though no source reveals how she met the heir to the throne, Procopius reckons that they must have met once she returned to Constantinople in the year 520 CE or so. Likely, Justinian soon fell under the spell of the brilliant and beautiful Theodora. Unable to marry on account of a law that prohibited nobility from marrying actresses, Justinian entreated his uncle, then Emperor Justin (c 450 – 527 CE) to intervene. But although Justin was amenable to assisting his nephew, his wife, Empress Euphemia was not and resolutely opposed Justinian’s intended marriage to the actress/prostitute. After her death, however, Justin conferred nobility on Theodora thereby paving the way for Justinian and Theodora to marry. Of this marriage the classist Procopius haughtily sneers: “From that moment he lived with Theodora as his legal spouse, thereby enabling everyone else to get engaged to a harlot.” To be sure, their marriage would send shockwaves throughout the Byzantine aristocracy. In 527 CE, while in ill-health, Justin crowned both Justinian Augustus and co-emperor and Theodora as Augusta. After Justin’s death some four months later, this humble daughter of a bear keeper and former actress would go on to fully fray the delicate societal fabric and become empress of the Eastern Roman Empire.

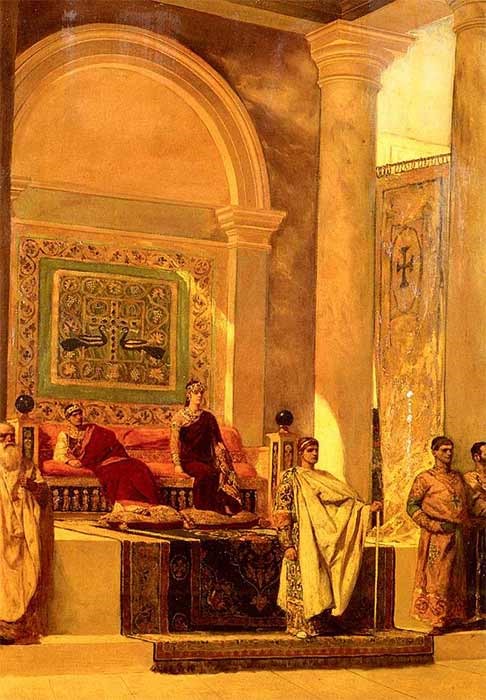

Perhaps it was because of her humble origins that Justinian’s court became notable for the groveling it required from visitors—something that did not bode well with the elite. To be sure, all royal guests—-regardless of their lineage—were expected to prostrate themselves face down with their lips touching the imperial feet. However, it was not just Justinian’s feet who were thus honored, Theodora’s were as well. Reveling in the pomp and circumstance of being royal, since she shared leadership with Justinian, Theodora expected every sign of deference awarded to the emperor. But who could blame her? From the beginning she was involved in all aspects of governance, participating not only in political strategies and planning but also in state councils as well. Though never officially co-regent, Justinian considered Theodora his partner in power, once calling her “partner in my deliberations,” and openly acknowledging that he consulted with her on many issues.

From the beginning, one of Theodora’s chief goals was to help the unfortunate—particularly women in need who engaged in prostitution. Fighting against its purveyors, she helped rid Constantinople and cities throughout the empire of brothel keepers for whom prostitutes were virtual slaves. Moreover, Theodora supervised the building of the Convent of Repentance, which housed and supported former prostitutes, setting up an endowment that added ancillary buildings to the convent complex. She also contributed financial aid to the women for buying necessities such as clothing and supplies. Since marriage and security for former sex workers were unlikely, her goal was for the women to live moral lives in relative comfort so they would not be tempted into a life of prostitution once again. With her strong sense of purpose, Justinian would come to rely on Theodora’s keen intellect and political acuity, but it was not until the winter of 532 CE that she showed him her steely will and strength of character.

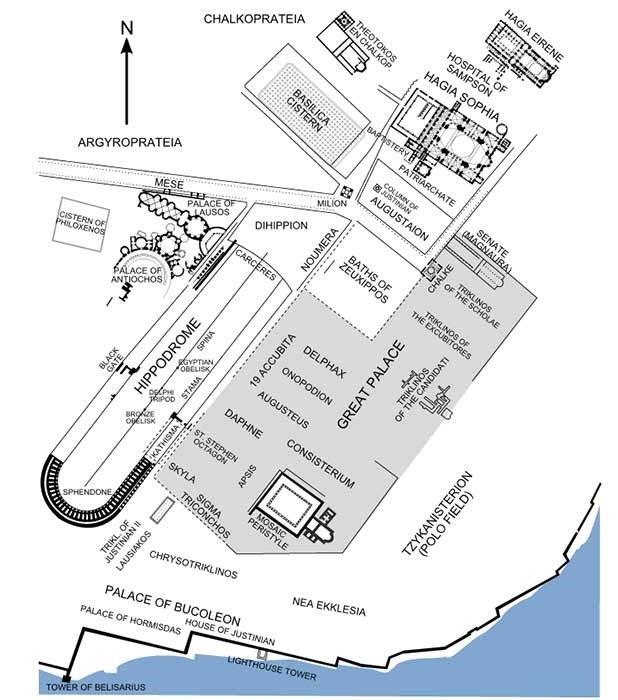

Could the raging riots which burned down more than half of Constantinople have stemmed from something as innocuous as a chariot race—a popular pastime of the Byzantine era held in the Hippodrome? Color-coded to help the fans distinguish between the two leagues, the Greens and the Blues represented public entertainers in such professions as charioteers, dancers, mimes, and so forth. Fan loyalty, however, was not restricted to entertainment and the factions would often take political stands where rivalry could turn into street fighting. In an event known as the Nika (conquer) Revolt, the two sparring factions—-the Greens and the Blues—- became united against Justinian on account of his refusal to pardon convicted felons from each of their camps. Another narrative reveals that the riots may have also been an outcry against the sovereignty of Theodora who upset the social order by marrying Justinian.

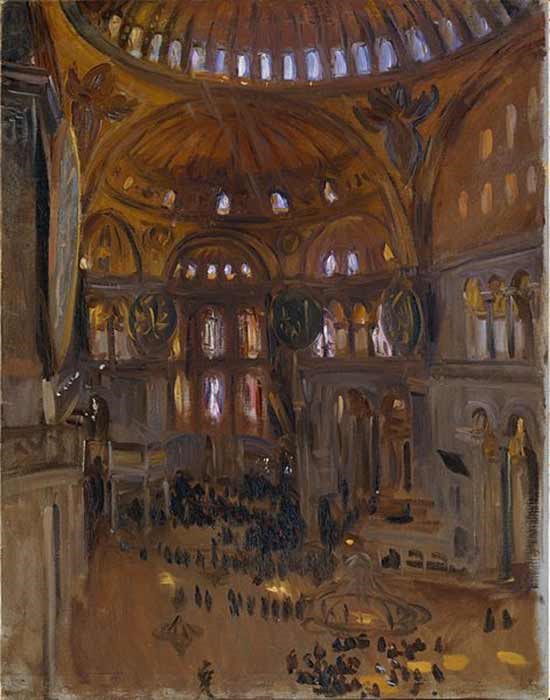

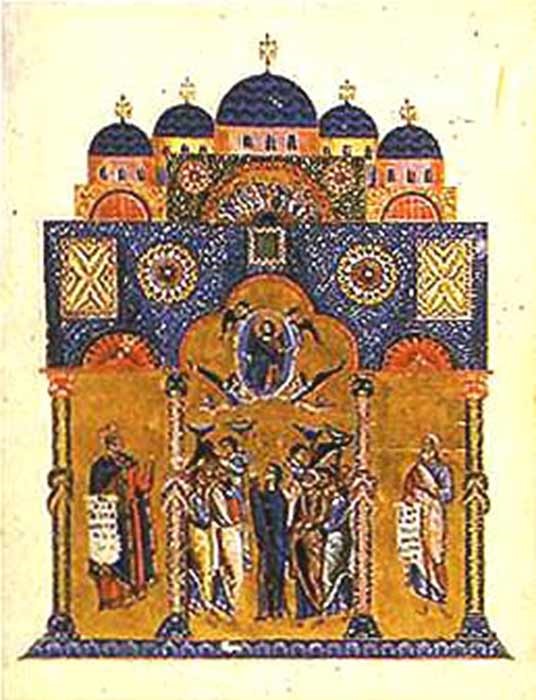

Regardless of motive, the leaders of the riots are believed to have been the nephews of Justin’s predecessor Anastasius I (431- 518 CE) —-Hyaptius, Pompeius, and Probus. Ultimately, the rebels rioted and burned down more than half the city, focusing on religious and imperial buildings such as the Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom) — the principal church of Byzantium. An aside, the Hagia Sophia would be rebuilt between the years of 532-537 CE and become the crowning architectural achievement of Justinian’s reign. Lacking anything resembling a modern police force, the emperor turned to his militia who were untrained to quell street protests and were soon overcome. Spiraling out of control, the crisis had become so bleak that instead of debating how best to remove the rioters the Senate was debating how best to remove the royals. Meanwhile, Justinian and his retinue were holed up in the imperial palace where they began planning their exit strategy—fleeing Constantinople in a boat under cover of darkness. But Theodora had other plans.

Changing the course of history, the empress—ever the actress—took center stage with a stirring speech that roused both the emperor and his attendants: “While it is the condition of our birth to die, it is unendurable to descend from imperial power to the state of a fugitive. God forgive that I should ever be without this purple robe: may I not outlive the day when I cease to be greeted as empress! If safety is what you want, my emperor, it’s easily had. We have plenty of money; there’s the sea; there are our ships. But look out that when you are safe you don’t discover that death would have been preferable. For my part, I like the maxim, ‘Kingship makes a good burial shroud.’” The most esteemed Augusta had no enthusiasm for returning to the life of a commoner. A sovereign through and through, it would take more than a riot—- that would burn to a crisp more than half of Constantinople —-to remove the imperial purple from her grasp.

Compelled to action by Theodora’s moving speech, Justinian and his generals, Belisarius and Mundus, concocted a last-ditch effort to lure the rioters into the Hippodrome by spreading a story that Justinian would be there. Tens of thousands of people—most (but not all) of them rebels—-came out for the big event. But, alas, once the soldiers sealed off the exits at the Hippodrome, they killed everyone in their path. It is believed that up to forty thousand people perished in a massacre which is credited for saving Justinian and Theodora’s reign. Though stories vary on how the nephews of Anastasius I were brought to justice, most historians concur that while Justinian favored leniency, Theodora—notorious for her ‘take no prisoners’ approach—insisted on their executions.

Although Theodora’s authority was significant before the Nika Revolt, her even greater influence afterward is reflected in many of the reforms Justinian put forward which promoted the rights of women—heretofore, an unimagined concept. In 534 CE, Justinian passed legislation prohibiting anyone from coercing a woman—slave or free—from working in the theater if she was unwilling, or to impede her if she chose to leave it. In another law with enormous implications for women of all social classes, Justinian vindicated the rights of women to own property and to inherit as well as advancing marriage and dowry rights for them. Furthermore, anti-rape legislation was passed in addition to laws supporting young girls who had been sold into sexual slavery. Theodora’s power was so considerable in getting the legislation put through that she is mentioned in nearly all the laws passed pertaining to the rights of women.

But women were not the only oppressed group whose rights she championed. Not known for doing anything by halves, Theodora was a tireless advocate of her adopted and oftentimes beleaguered faith—-Monophysitism. Some background on the split in the Christian church is useful. In 451 CE, the Council of Chalcedon ruled that Christ had two natures—human and divine. Supporters of this edict became known as “Chalcedonians.” The ruling, however, was in direct opposition to Monophysitism which held that Christ had only one nature which was divine. But the schism was, in fact, as much regional and cultural as it was religious. Encompassing the Greco-Roman world, much of the Western part of the Byzantine Empire agreed with the Roman Pope and considered itself Chalcedonian. Whereas in the East—especially in ancient strongholds like Egypt and Syria—Christians were predominantly Monophysites and represented by various Patriarchs.

Because the Monophysites were often persecuted within the orthodox Byzantine Empire, Theodora became their vehement advocate providing shelter for the covert clergy within the Boukoleon Palace complex. It is believed that over several hundred of the persecuted clergy at one time or another lived under Theodora’s protection. Forasmuch as Theodora was committed to her faction, an unrealized dream of Justinian’s—-who was himself a Chalcedonian—was uniting the two disparate faiths. Nevertheless, despite his desire to unify the church—or perhaps because of it—Justinian chose to look the other way when it came to his wife’s activity on behalf of the clandestine Monophysites. So, it would appear that at least regarding religion, Justinian and Theodora were at cross-purposes. While Justinian wanted to mend the rift between the Chalcedonians and the Monophysites, Theodora’s powerful intervention contributed to the resolve of the oppressed Monophysites further deepening the divide. Over the years, historians have speculated that Theodora’s fierce advocacy on behalf of the Monophysites ultimately may have weakened Christianity’s overall message, especially in the East where the Monophysite presence was most strongly felt. They argue that Monophysitism might have died an early death if not for the considerable intervention of Theodora. Did Theodora unwittingly weaken Christianity’s message in the East, perhaps opening the way for the spread of a new religion in the region? Indeed, a span of fifty years separates the death of Theodora and the birth of Mohammed. Many believe that Christianity’s lack of cohesion—for which Theodora played a role—may have been one of several factors encouraging the expansion of Islam in the region.

Religion and women’s rights, however, were not the only areas in which she made her strong presence felt, in fact, Theodora exerted considerable influence in all facets of governance—and she had the enemies to show for it. Though his jabbering may be questionable at times, Procopius is not the only ancient who reports about how she had a hand in dispatching some of her foes. Yet she is hardly alone among sovereigns to do so which may be why they are so seldom canonized—- that is, except for this most singular of sovereigns. While scholars today cast Theodora as neither sinner nor saint, it may seem surprising that she has joined the haloed ranks of the latter. In February of 2000, fifteen hundred years after her birth, Theodora’s voice was still making itself heard when she was beatified by the Patriarch of Antioch––head of the Universal Syrian Orthodox Church—the church the empress helped found. Furthermore, she is celebrated as Saint Theodora in the Greek Orthodox Church as well.

Although her bad press began with Procopius; it did not end with him. It is no secret that history has been unkind to Theodora—she was fearless, she was fierce, and she was female oftentimes a combination that does not bode well with most historians—-ancient or otherwise. A strong voice for the weak, Theodora was a champion of the powerless, which often found her in the crosshairs of the powerful. The truth is she did more for women, the disadvantaged, and the religiously persecuted in her short life than most monarchs would do in many lifetimes. One of the most triumphant of all female rulers, no empress before or after could boast of having achieved greatness from such reduced beginnings. Yet she did not lead alone. It is an irony that the superlative power couple credited with ushering in one of the most productive periods of the Eastern Roman Empire would produce no children. However, when she could not reproduce a dynasty of her own this strong-willed empress tried to manufacture one. Envisioning a Monophysite dynasty, she attempted to marry her nephew to the daughter of Belisarius—if she had lived longer, she might have even pulled it off.

Although fifteen years his junior, Theodora predeceased Justinian by seventeen years when she died—likely from breast cancer— at less than fifty years of age. Because she knew that the Monophysite religion would be greatly diminished by her passing, on her deathbed Theodora begged Justinian to continue to house the besieged Monophysite refugees. To be sure, Theodora was hardly cold in her grave before the Chalcedonians sought to expel the vulnerable Monophysite clergy from their sanctuary. But Justinian held fast to his promise and would continue to house the Monophysite refugees for the next seventeen years. Her body was laid to rest in the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople.

Reference List

Bradshaw, Gillian. 1987. The Bearkeeper’s Daughter. Penguin Books.

Cesaretti, Paolo. 2001. Theodora, Empress of Byzantium. The Vendome Press.

Evans, James Allan. 2002. The Empress Theodora: Partner of Justinian. University of Texas Press, Austin. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44172751.

Foss, C. 2002. The Empress Theodora. Byzantion, Vol. 72, No. 1.

Mallet, C. E. January 1887, The Empress Theodora. The English Historical Review, Vol. 2, No. 5. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/546828.

Procopius. 2007. The Secret History. Translated by G.A. Williamson and Peter Sarris, Penguin Books.