History has long been unkind to Fulvia (85/80 BCE-40 BCE)—the notoriously jilted wife whom Mark Antony abandoned for the Queen of the Nile. The ancient chroniclers portray Fulvia as a jealous and vengeful wife, claiming that she committed numerous atrocities. These include inciting a riot in the Roman Forum that destroyed the senate house, repeatedly stabbing the tongue in Cicero’s decapitated head, and initiating a war with Octavian—Rome’s future emperor known to posterity as Augustus—in an attempt to entice her husband back to his matrimonial bed. The ancients denounced and disparaged Fulvia in the most heinous terms simply because she dared to defy patriarchal notions of femininity. Ancient Rome chastised women for drawing public attention to themselves or usurping male authority, considering modesty and humility as prime feminine virtues. Clearly, Fulvia was a woman who did not know her place.

More than just a footnote in the annals of ancient Roman history, most historians are quick to overlook that Fulvia had once been Rome’s most admired woman. She was the first non-mythological woman to appear on Roman coins and used her political influence to challenge the traditional gender roles expected of Roman matrons. Married to three powerful political figures, Fulvia was not content to wile away the hours with the feminine pursuits of spinning or weaving. During a time when historical narratives largely relegated women to the background, Fulvia encroached on the masculine pursuits of politics and military, leading ancient chroniclers to unfairly portray her as envious, vengeful, and troublesome, akin to the goddess Juno. This portrayal, in fact, persists even among modern historians, who often accept the misogynist biases of the ancients as incontrovertible facts. But are these depictions fair? What was her often overlooked role in the political dynamics of the day? How did her actions not only influence her husbands’ legacies but also leave an indelible mark on the power structures of the time?

Born the daughter of Marcus Fulvius Bambalio and his wife, Sempronia, Fulvia’s paternal lineage was among the most esteemed plebeian families of the Roman Republic. The Fulvii’s prominence in Roman politics began in 322 BCE when Lucius Fulvius Curvus became the first member of the family to achieve the consulship. Although the year of her birth is unknown, in 62 BCE, she married her first husband, the controversial senator and tribune, Publius Clodius Pulcher. If she was like most Roman girls from elite families, she would have been around fourteen to fifteen years of age upon her marriage.

Originally from the patrician class, Clodius’s burning ambition was to serve as a tribune of the plebs, so he made the highly unusual move of having himself adopted into the plebeian class. A majority of Roman citizens belonged to the plebeian class, and as such it held the most sway in Roman politics; Julius Caesar represented the plebeians and supported Clodius. Because of his backroom machinations, Clodius would become Rome’s most influential tribune in almost sixty years. Considered the “people’s hero,” during his tenure, Clodius implemented notable reforms (Leges Clodiae) on behalf of the plebeian class. While not legislating however, Clodius and his group of supporters frequently incited violence against his political opponents—of which there were many. A skirmish with another political rival, Milo, led to Clodius’s death in January of 52 BCE.

News of Clodius’s murder reached Rome before his body did, and because Clodius was second in popularity to Julius Caesar himself, his supporters lined the streets in front of their home in no time.

One may assume with the death of her husband, Fulvia’s position was now in peril. Fulvia, however, had other plans; she did not let mere death end this complicated man’s story. The gods blessed Fulvia and Clodius with two children and by all accounts they had a successful marriage. One can imagine how the young widow would have been grievously distressed to learn of her husband’s assassination. All the same, in what many believe was her political debut, Fulvia made a massive demonstration of public grief that had a deep influence on the citizenry. Wailing, beating of the chest, pulling of the hair, and scratching of the cheeks were customary displays of public grief for widows in the late Roman Republic.

In addition to grieving, as the female head of household, Fulvia was in charge of preparing the corpse for public viewing. Instead of presenting Clodius’s body after purification and cleansing as was customary, Fulvia allowed the public to view his badly mutilated, unwashed, and bloodied body. According to the Roman rhetorician, Asconius, a large crowd surrounded Clodius’ corpse while Fulvia “kept pointing out his wounds, while pouring out her grief.” Although the public expression of her sorrow roused the throng, the deliberate display of Clodius’s severely injured body further incited the people. She was actively grieving the loss of her husband, but she was also attempting to maximize the political advantage that her public display would generate. Overnight the crowd doubled in size and tripled in ferocity.

To further rile up the crowds, Fuliva authorized two tribunes to carry her husband’s naked and battered corpse to the Forum for display on the rostra, the speakers’ podium facing the senate house. The tribunes stirred up the growing masses by spouting about their leader’s murder, revealing Clodius’s unwashed and gaping wounds for all to see. The crowd’s emotions flared, calls for vengeance echoed throughout the air, and tensions rose. Instead of building the customary funeral pyre outside the city walls, the hordes, in their fury, placed Clodius’s corpse on top of a makeshift funeral pyre in front of the senate house. The flames grew as out of control as the mob, swiftly destroying the senate house and another government building.

To keep the death of Clodius in the public eye, detractors accused Fulvia of continuing to make a colossal show of her mourning. Amidst the tumultuous world of Roman politics, Fulvia’s grief united those who sought revenge and justice for Clodius. It was the custom in ancient Rome for widows to wear dark clothing, including a cloak and a head covering, for a period of ten months after their husbands’ death; they were also expected to avoid makeup and jewelry. The young widow’s stark appearance, with her two children in tow whenever she appeared in public, powerfully brought the people’s loss to light.

Three months failed to quell the political firestorm surrounding Milo’s trial which commenced in April of that year. In Rome, trials took place outdoors for public observation, but due to the volatile crowds, the presiding magistrate called for an armed guard to maintain order. The impact Fulvia had after her husband died was substantial, but she took it to a new level during the trial when she testified for the prosecution. Fulvia’s testimony came last, indicating the prosecution’s high esteem for it.

Although her words were not preserved for posterity, Asconius reports that her emotional appeal, “greatly moved those who were in attendance.” Cicero, one of the greatest orators of the time, advocated for the defense, but Fulvia and the hostile Clodian faction so flustered him that he became tongue-tied and inarticulate while speaking on behalf of Milo. Fulvia’s growing influence and prestige enabled her to sway public opinion which helped convict Milo, leading to his exile in Massilia (today’s Marseille, France).

As the widow of the “people’s hero,” Fulvia had established a name for herself, yet she had to exert her political influence through her husband—-women in ancient Rome were not allowed to vote, let alone hold public office. To continue to exercise power, she had to remarry. Within a year, Fulvia married Gaius Scribonius Curio. Although Curio was a political leader before their marriage, marrying Fulvia was a milestone in his career, as it placed him as the heir to Clodius’ populist empire, giving him ever more political capital. Like clockwork, a year after their marriage, Curio became Tribune of the Plebs in 50 BCE. However, Curio’s candle was brief; like most politicians of the day, he was a military man and lost his life during the early stages of Caesar’s civil war against Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey) in 49 BCE in today’s Tunisia.

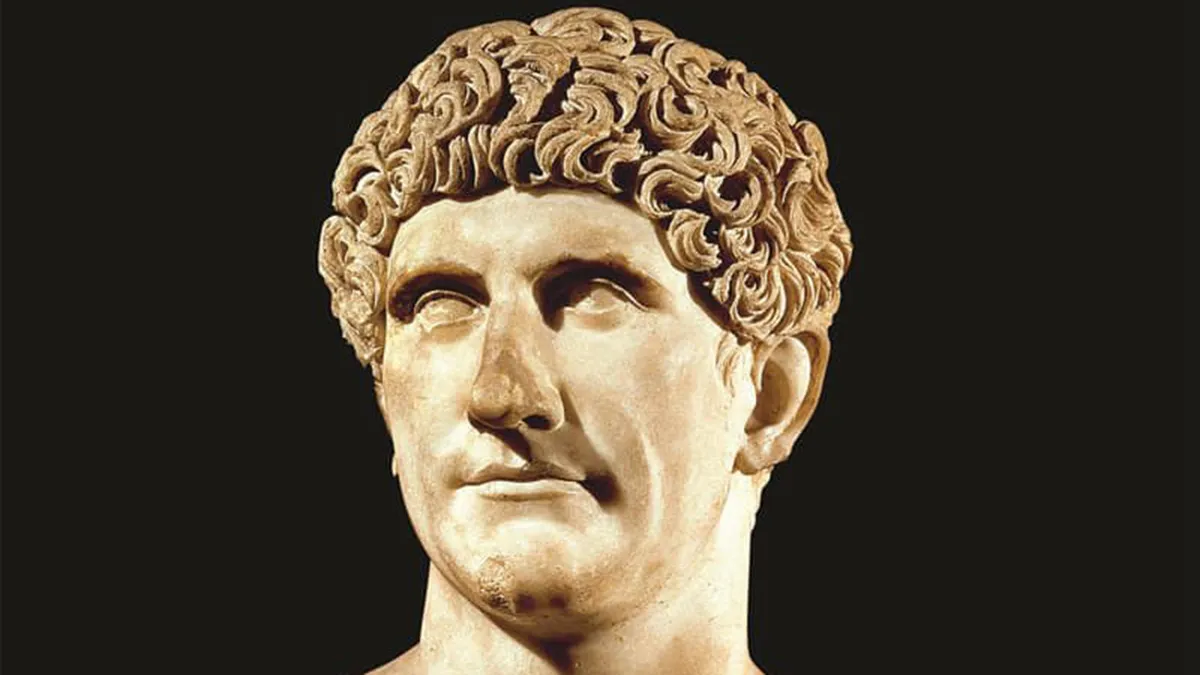

Fulvia was not only able to provide financial support to her next husband, but she was also a skilled political organizer with a substantial Clodian following that aligned with Caesar’s objectives. Thus it is no surprise that once she was again a prominent widow, she caught the eye of Mark Antony, a celebrated leader and one of Caesar’s favorites. Believed to have descended from Hercules himself, the handsome war hero and politician, was a catch. As one of the most prominent legislators at the time, Fulvia had reason enough to marry Mark Antony, except for one small detail—he was already married. Antony, however, was never one to let wedlock stand in the way of an advantageous alliance. He publicly declared his second wife’s (Antonia) infidelity with a political leader (Dolabella)—disposing of an inexpedient wife while disgracing a political adversary. A public accusation of adultery in Rome was a socially acceptable way for a husband to divorce his wife—and to keep her dowry.

Regardless of what they may have felt for each other, Fulvia and Antony’s marriage in 47 BCE was a politically advantageous partnership. United, they formed a powerful political entity within Rome.

Nonetheless, they may not have anticipated the scrutiny they would both face following the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE. Because Antony and Caesar shared the consulship that year, after Caesar’s death Antony was now the first in command and faced the challenging predicament of maintaining peace. Although the majority of the Senate backed Caesar’s assassins, few could tolerate additional violence. Even so, in order to protect Caesar’s legacy and consolidate his own backing, Antony roused the people when, during the reading of Caesar’s will, he revealed that the fallen statesman had bequeathed his gardens, along with cash for distribution, to the public. Straightaway, the people were incensed about Caesar’s murder and vowed revenge. Soon after, the main conspirators in Caesar’s assassination, Brutus and Cassius, lost their provinces and fled from Rome.

Mark Antony was now at the height of his influence and popularity in Rome. As the sole consul, Antony served as the chief executive of the Roman state; he presided over the Senate and commanded the Roman army, in addition to holding the highest judicial and religious authority in the land. The Romans, however, harbored a strong aversion to monarchy due to the tyrannical nature of their previous kings. Caesar’s increasing authoritarianism, particularly his installation as dictator for life in 44 BCE, led many senators to support his assassination. With his rising prominence and intense popularity, Antony took over where Caesar left off.

To be sure, not everyone was thrilled about Antony’s rise to prominence. As a staunch defender of the Republic, Cicero had seen Caesar’s growing influence as a threat to republican values. Thus, when Antony supplanted Caesar in the hearts and minds of the Romans, Cicero composed a series of fourteen speeches, known as the Philippics, for the Senate and, to a lesser extent, the Roman citizens, denouncing Antony’s increasing power. Cicero’s actions, however, extended beyond targeting Antony. Despite having spent the majority of her life in public view, following Caesar’s assassination and Antony’s rise to power, Fulvia became the center of attention—and frequently where Cicero’s poison pen took aim. No author denigrated Fulvia more incessantly than Cicero, who referred to her as “the most avaricious, cruel woman” and a “bloodthirsty degenerate” while denouncing her involvement in political affairs.

Time did not quell Cicero’s ardour. When Antony was abroad in March of 43 BCE, a year after Caesar’s assassination, Cicero campaigned for Antony to be declared hostis or “enemy of the state.” Fulvia, never one to sit idly by, sought to counter this by garnering support for him, aided by her extensive network of Clodian loyalists who complied with her directives. The night before the Senate was to decide the issue, Fulvia, along with her sons and Antony’s mother, dramatically appealed to senators for support. Because of her efforts she was able to stave off the declaration for months.

Cicero’s public relations campaign against Antony had an unlikely beneficiary—Caesar’s eighteen-year-old great-nephew and heir to the bulk of his estate, Gaius Octavius, known during this time as Octavian. Octavian arrived in Rome from his studies in Greece less than a month after Caesar died; Caesar’s soldiers and the general populace warmly welcomed him along the way. According to custom—and to strengthen his ties to his great-uncle Julius—Gaius Octavius became Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (later Augustus). Moreover, Octavian sought formal recognition as Caesar’s adopted son, necessitating the enactment of specific legislation. Antony, however, had already made an effort to establish himself as Caesar’s political heir. The conflict between the two men was cast.

The political situation in Rome was unstable for some years after Caesar’s assassination. Various factions competed for control, resulting in a series of confrontations that would eventually transform the Roman Republic. In April 43 BCE, the Senate formally declared Antony an enemy of the state, demonstrating Cicero’s unwavering determination. Not only did this proclamation result in the loss of Antony’s legal authority within the Roman political system, but Antony was now regarded an outlaw in his own city, allowing the Senate to take military action against him.

In just a few short months, Fulvia’s influence with the Clodian faction and her tireless efforts to maintain Antony’s popularity with his troops were critical in shaping an alliance with Octavian and Marcus Aemillius Lepidus (a general in Caesar’s army),

Despite their rivalry, Antony and Octavian united against Brutus and Cassius to avenge Caesar’s murder, transforming Antony from an enemy of the state into a powerful Roman leader once again. In November of 43 BCE, the three men formally established the Second Triumvirate, dividing the Roman domain into three, with each triumvir claiming a territory. Octavian assumed responsibility for the West, which included Italy, Gaul, and Spain, Antony for the East, which included Greece and Egypt, and Lepidus for the South, which included Africa. Octavian’s betrothal to Fulvia’s daughter—by Clodius—Claudia, sealed the pact of the Second Triumvirate, further solidifying Antony’s position in the alliance. Moreover, during the formation of the Second Triumvirate, Antony insisted on the inclusion of Cicero in the list of proscribed individuals, leading to his condemnation to death. Fulvia was sometimes disparagingly referred to as the “fourth triumvir” due to her vast influence.

On October 23, 42 BCE, in Philippi, Macedonia, the conclusive defeat of Brutus and the Republican forces transpired, establishing the triumvirs as the undisputed sovereigns of Rome. After the victory at Philippi, Cicero was assassinated. To symbolize his voice and writings, his head and hands were cut off—-and as a warning to others—-nailed to the rostra, the speaker’s platform at the Forum. Nearly three hundred years after the event, Cassius Dio would write how Fulvia pulled out Cicero’s tongue and pierced it with golden pins she used in her hair. Today most historians question this bit of ancient hyperbole.

The uneasy alliance between Antony and Octavian was short-lived—and according to the ancients—it was all Fulvia’s doing. It was her involvement in the Perusine War of 41 BCE that garnered the most criticism. Ever the indefatigable advocate,Fulvia concentrated her efforts in Italy on maintaining Antony’s popularity among his soldiers in the West, while Antony was in the East. Fearing Octavian was gaining the veterans’ loyalty through his land grants, Fulvia made frequent trips to Antony’s legions to inform the soldiers that it was Antony, not Octavian, who was awarding them land grants. The tensions between Octavian and Fulvia reached a fever pitch when, in a fit of rage over her interference, Octavian divorced Fulvia’s daughter and famously sent her home to her mother, supposedly intact after two years of marriage.

By giving the veterans land grants, however, Octavian incited the ire of the dispossessed Italians. Lucius Antonius— Antony’s younger brother—- who was holding the consulship at the time, had his own agenda for opposing Octavian; according to Appian, it was his intent to overthrow the triumvirate. Recognizing this as an opportunity, he mobilized the dispossessed Italians. Unlike Fulvia, whose interests were her husband’s, Lucius confused the situation by favoring the displaced landowners over the veterans.

The conflict intensified into military action when Lucius dispatched Fulvia and her children to Preneste (today’s Palestrina), north of Rome, for the inauguration of a new military colony; however, Octavian deployed soldiers against them, necessitating a bodyguard for their return journey. Lucius then organized the landowners to march onto Rome. After failing to take it, they marched north to Perusia (today’s Perugia). Although Fulvia did her level best to unite the veterans and landowners—with Antony sitting on the sidelines—her efforts came to naught. While initially Fulvia chastised Lucius for “stirring up war at an inopportune time”, ultimately she supported him from her base in Preneste. Together, they had raised an army of eight legions, with Fulvia assuming command when Lucius sought refuge in Perusia during Octavian’s siege.

For giving orders to the legions, Dio rebukes Fulvia, asking, “And why should anyone be surprised at this, when she should wear a sword around her waist, give out a password to the watch, and even address the troops directly on occasion?” Although Fulvia provided reinforcements to Lucius, Octavian’s forces surrounded Perusia in the end, starving Antony’s troops, executing its citizens, and plundering the land. During the ensuing massacre, Octavian spared Lucius, Fulvia, and numerous high-ranking supporters, allowing them to depart from Italy. Fulvia and her children traveled to Greece to meet Antony, but she died soon after, likely of having contracted an infection on the long boat ride from Rome to Greece.

In the lost Memoirs of Augustus, Octavian deliberately shifts the blame for the war from Lucius to Fulvia. Upon her demise, Fulvia became a suitable scapegoat for the two triumvirates, who readily reconciled, attributing the conflict to her actions. Their propaganda against her continues to be as effective today as it was over two millennia ago. Straightaway, the warring triumvirates forged a new pact; they would form one big, happy family when Antony married Octavian’s sister, Octavia. According to some accounts, Antony and Octavia tied the knot within a few days of Fulvia’s death.

As it stands, history would confirm that Fulvia was a guiding influence in Antony’s political life. Would Octavian be a postscript in the historical record if Antony had followed his wife’s lead? Today many historians believe that if Antony and his generals had supported Fulvia’s efforts rather than sitting on the sidelines, they may have successfully ousted Octavian. While Fulvia endeavored to safeguard their legacy for her five children, two of whom were Antony’s sons, Antony found himself holed up with Cleopatra and the numerous distractions of Alexandria. The ancients made much of this irony and attributed the most banal feminine traits to Fulvia, unfairly portraying her as the jealous wife who initiated a war to return her husband to his matrimonial bed. This sweeping generalization neglects the political acumen and drive Fulvia had demonstrated during her notable political career. Through her powerful political network, Fulvia tirelessly defended Antony’s interests and safeguarded his reputation, rejuvenating him from an enemy of the state into a dominant Roman leader once again. Without her support, Antony would have remained an outlaw instead of becoming one of the Roman Republic’s most compelling triumvirates.

But she did not only impact her husbands’ legacies; she significantly influenced the tumultuous political climate of her day. Far beyond those of a rejected lover, Fulvia’s actions throughout her political life demonstrated a strategic initiative that impacted and influenced the patriarchal landscape of Roman politics.