In Euripides’ Medea (431 BCE), Medea’s wrath against Jason’s betrayal was so fierce that the phrase “hell hath no fury like a woman scorned” might have been written with her in mind. In the play the ever-ambitious Jason finds it effortless to desert his foreign-born wife, Medea, and two sons for an advantageous marriage with the Princess of Corinth. Using her sorcery against Jason—for a change—Medea kills both her rival and her rival’s father, King Creon—at whose connivance the ill-fated union between Jason and his daughter was hatched. These two murders seem rational, even justifiable. After all, not only was Medea being replaced by someone younger, blonder and more socially elevated but to add insult to injury, the king was banishing Medea—from her adopted home in the city-state of Corinth. Can you blame her for being furious?

But… Medea crosses the line into depravity with the cruel slaying of her two young sons whose only sin was being borne from Jason’s seed.

In a move that hurt her as well as him, punishing her errant husband by killing their two boys seems both extreme and unjustifiable. In the dramatic conclusion of the play Medea is suspended aerially and rises triumphantly above the stage as the deux ex machina—god from the machine.

Looming large against her human adversaries, with her two dead children in tow, she is seated majestically in a dragon-drawn golden chariot sent to her by her grandfather—the Titan sun god, Helios.

Looking up at her in helpless resignation, a bewildered Jason curses Medea as a “hateful thing….utterly loathed by the gods,” but like much of what Jason utters throughout the play, he is wrong.

In fact, quite the contrary is true.

……………………………

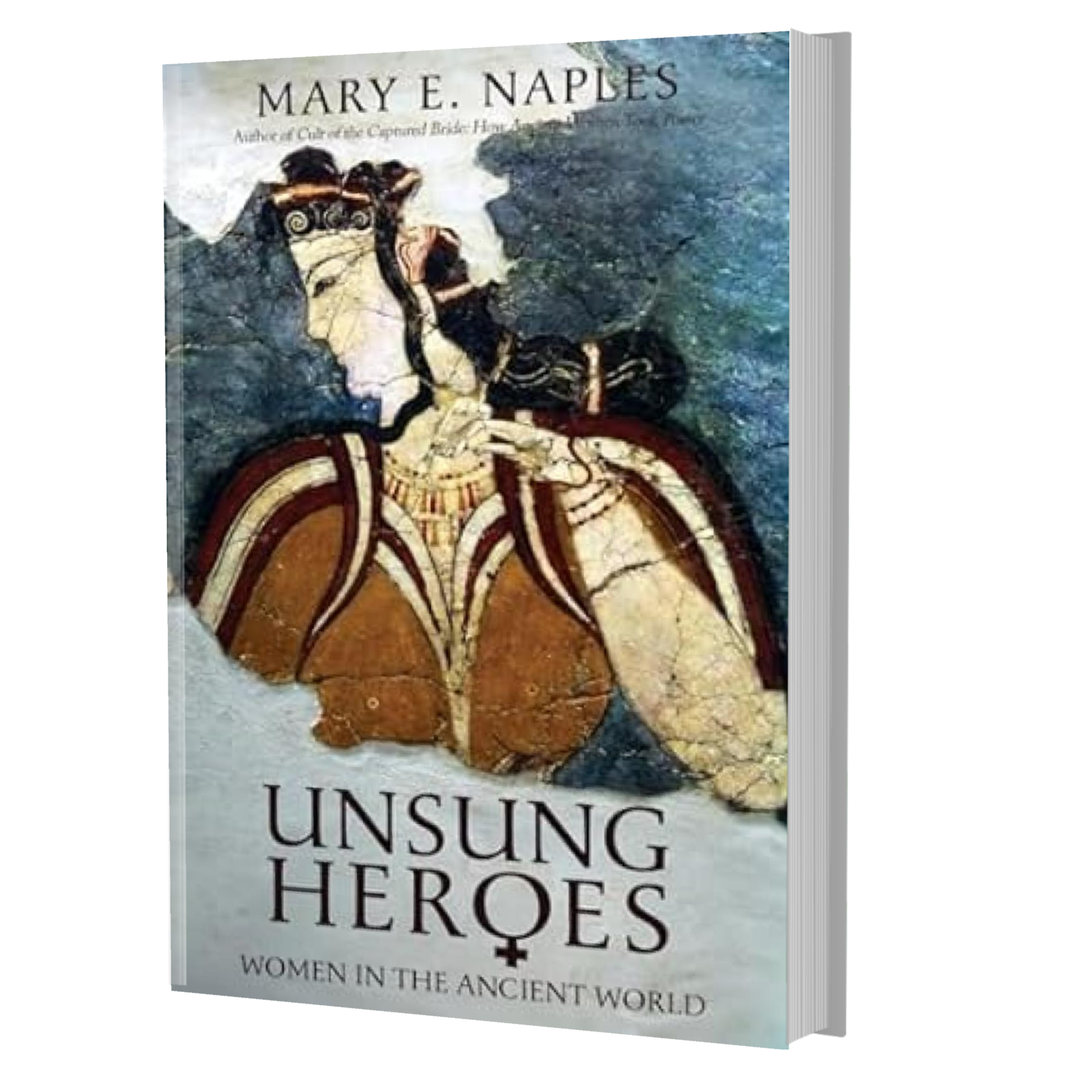

Why did the gods support Medea in her ultimate revenge against errant husband? Find out in my book Unsung Heroes on Amazon.