At first glance, it would seem that Medusa, the mortal Gorgon with writhing snakes for hair, wide glaring eyes, and a protruding tongue, is the least likely of all characters in Greek mythology to be a fashion and cultural icon. Yet, the opposite is true. Although her appearance was said to be so hideous that she could turn men to stone, Medusa has been immortalized by artists throughout the ages with a countenance that remains ubiquitous.

In the ancient world, her unique visage—occasionally adorned with boar-like tusks, bronze hands, golden wings, and a gaping mouth—was frequently depicted on statuary, shields, roof tiles, entryways, and floor mosaics to scare away enemies. Due to her association with Athena, she even adorned the Sicilian flag, where she still resides today. Currently, Medusa’s distinctive likeness can be found on clothing, mugs, eyeglasses, hair accessories, and jewelry and serves as the emblematic icon for a major fashion house.

Numerous artists, writers, and filmmakers have drawn inspiration from her fierce beauty and tragic story. As a symbol of empowerment and resistance, Medusa often embodies revolt, representing the struggle against oppression and the reclamation of the feminine narrative.

Beset by misfortune and misinterpretation, Medusa is frequently scorned within Greek mythology but beneath her grotesque facade exists a complex narrative interlaced with themes of beauty, metamorphosis, and victimhood. Upon recounting, her story warrants compassion instead of contempt. This study examines the figure of Medusa and analyzes her complex myths and their reflection of Graeco-Roman civilization. While the myths offer insight into classical society, can they also offer clues about Medusa’s pre-Greek origins?

Cursed to a fate to which she fell victim, it should come as no surprise that Medusa is introduced into the canon of Greek literature by way of an insult. In Homer’s Odyssey (8th-7th century BCE) the fearless Greek hero Odysseus himself was frightened: “pale fear seized me, lest august Persephone might send forth upon me from out the house of Hades the head of the Gorgon, that awful monster.” This excerpt highlights the intense dread and aversion associated with Medusa, since even the mightiest of heroes can be paralyzed by her terrifying visage. Alas, poor Medusa, although the derisions begin with Homer, they do not end with him.

In his Theogony (8th-7th century BCE), Hesiod describes her as the only mortal among the three demon-like sisters known as the Gorgons. Her Gorgon sisters, Sthenno and Euryale, are often depicted as having serpentine hair, like Medusa, and sometimes boar-like tusks and wings. Unlike Medusa, the Gorgon sisters possessed immortality, allowing them to remain perpetually youthful. The Gorgons, along with other primordial marine beings, are the offspring of Phorcys and Ceto, ancient sea deities in the Greek pantheon who in turn were children of Gaia, the earth herself, and her son Pontus, representing the sea. The fish-tailed Phorcys and Ceto are siblings and consorts who ruled over vast marine creatures and the ocean’s deep waters; the needs for gods such as these highlights the Greeks’ fears of the sea’s many dangers.

Shortly after Hesiod presents Medusa, he narrates her unfortunate destiny. Being born mortal was bad enough, but then “the Dark-haired One (Poseidon—god of the sea, storms, earthquakes, and horses) lay down with her among the flowers of spring in a soft meadow.” Although Hesiod does not explicitly state it, whenever a god lies with a mortal in the Greek world, one can expect that rape or, at the very least, coercion is implicated. In the myth, male agency reduces Medusa to a mere object. After she suffers the sexual advances of a male deity, a now pregnant Medusa becomes a trophy prize for a self-serving hero.

The next line states, “So when Perseus later cut off her head, enormous Chrysaor sprang out, along with Pegasus, the horse.” Medusa’s curse, however, extends beyond losing her head. Although Medusa is considered a foreigner by the Greeks due to the bad luck of being born a Gorgon, she further loses her place in society when she loses her chastity; despite the fact that it was not her fault. In the Greek world, only chaste, obedient, and modest women garnered respect. Because of her diminished status, the myth does not challenge the morality of killing an innocent female, even while pregnant.

Medusa is not referenced again until the fifth century BCE, when Pindar, the famed Greek lyric poet, alludes to her briefly in his Pythian Ode 12. However, akin to all legends surrounding Medusa, the narrative predominantly focuses on Perseus’s heroic endeavor rather than the plight of the ill-fated maiden with serpentine locks. In the Ode, Pindar narrates that after Perseus, the son of Zeus (lord of the Olympian gods) and the mortal princess Danae, “stripped off the head of the beautiful Medusa,” her sisters pursued him. Upon failing to capture him, they lamented with a sorrowful dirge for their departed sister, emphasizing the deep connection among the Gorgon sisters and accentuating the tragic nature of Medusa’s fate. Euryale’s lament was so poignant that Athena is said to have created the aulos (flute) to replicate her mournful melody.

The next time Medusa is heard from is in a work by the author known as Pseudo-Apollodorus, titled Bibliotheca (The Library), which dates to the 1st or 2nd century CE. Once more, Medusa serves solely as a plot device in a hero’s quest, diminishing her depth and autonomy.

In the myth, Perseus and King Polydectes of Seriphus are at cross purposes. To eliminate Perseus, an obstacle in his quest for Danae, Polydectes dispatches him on a mission to behead Medusa, well aware that it is a useless undertaking likely to lead to the hero’s death. Despite the formidable difficulties, he convinces Perseus that success in his quest will give him everlasting fame.

Polydectes, however, is oblivious to the fact that Perseus’s father is the lord of the Olympian gods; hence, he inadvertently obtains heavenly assistance from Perseus’s half-siblings, the Olympians: Athena, the goddess of wisdom and warfare, and Hermes, the messenger god, who provide Perseus with necessary tools for his undertaking. He obtains a curved sword from Hermes, crafted to efficiently decapitate Medusa, and a polished shield from Athena, enabling him to view Medusa without direct eye contact, as such contact would lead to his petrification. The Olympians also recommend that he seek counsel from the Gorgons’ sisters, the three Phorcides, who were born elderly and possess a single tooth and eye among them. Ever-cunning, Perseus seizes both tooth and eye, withholding them until the Phorcides disclose the whereabouts of the Gorgons. The sisters surrender and furnish Perseus with tools that undermine their unfortunate sister’s destiny: Hades’ cap of invisibility, allowing him to see all without being seen; winged sandals to fly beyond the confines of the Greek realm where the Gorgons dwell; and a kibisis, or magic pouch, to contain Medusa’s severed head.

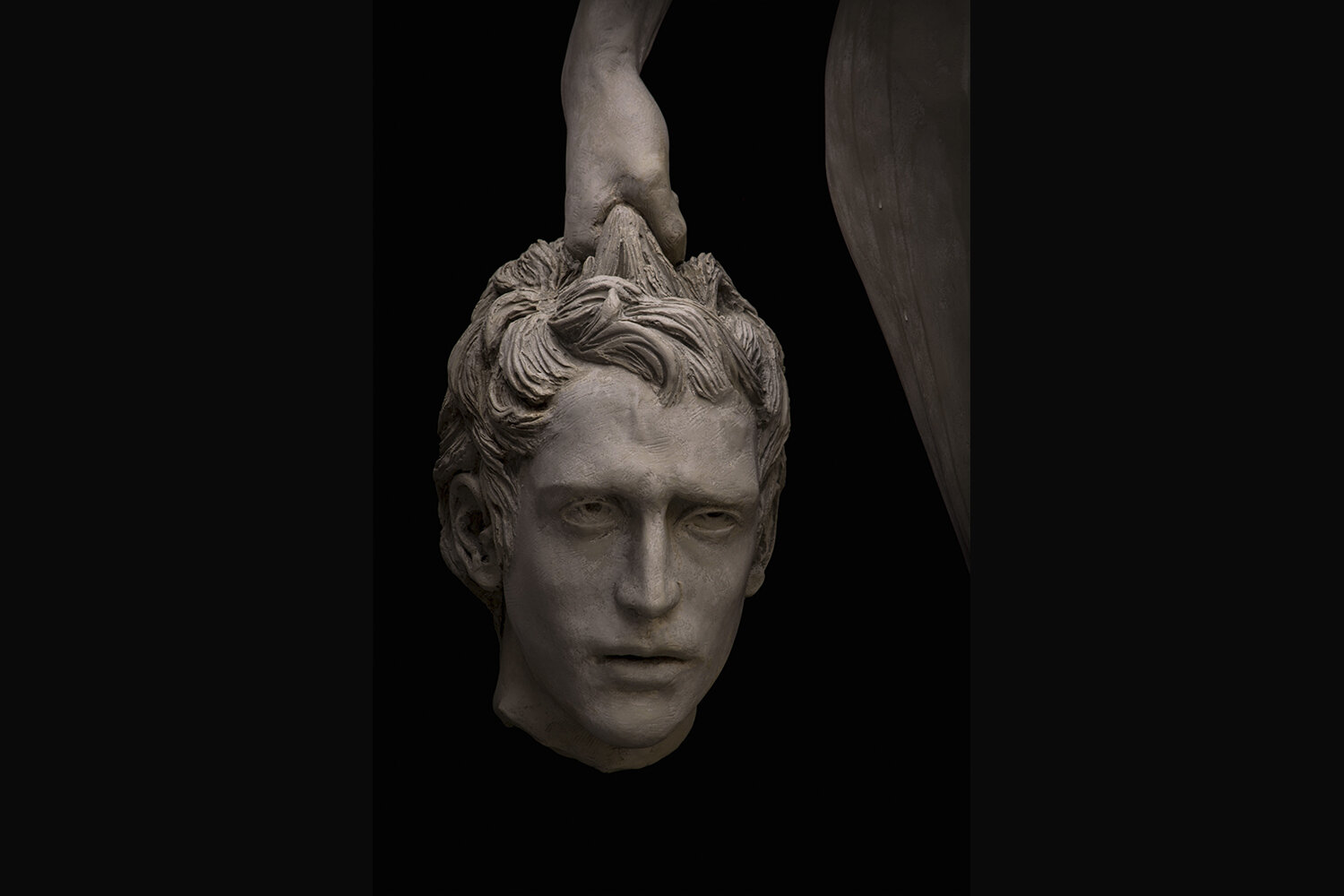

After the hero is equipped for his mission, while Medusa sleeps, Perseus stands over her: “…Athena guides his hand; he looks with an averted gaze on a brazen shield, in which he beholds the image of the Gorgon, and then he beheads her.” Perseus, the supposed hero, lacks the courage to behold Medusa’s slumbering visage even with her eyes tightly shut. This inverted narrative portrays the hero as the monster: a cowardly figure who murders a vulnerable, pregnant maiden merely for the pursuit of fame. Conversely, despite the misfortune of being born a Gorgon, the monster, who has committed no wrong-doing, is the true hero of the story; she displays a quiet type of heroism in having to endure the injustice and savagery imposed upon her.

Following Medusa’s demise, her progeny, Pegasus and Chrysaor, emerge from her, while Perseus seizes her head, which is bound to safeguard its slayer. Medusa’s lethal gaze transforms her head into a powerful weapon for Perseus, allowing him to petrify his adversaries.

Armed with these tools, a victorious Perseus fulfills his quest and delivers Medusa’s head to Athena, who affixes it to the middle of her shield to aid in repelling her numerous enemies. Like Medusa, to deter their adversaries, Greek troops, adorned their shields with the serpent-haired Gorgon, recognizable by its protruding tongue and distended eyes. Thus, Medusa was converted into an apotropaic symbol, functioning as a deterrence against the evil it represents. In the same way, Greeks adorned their entryways with Medusa’s likeness to discourage unwanted intruders. While her visage was unfortunate for Medusa, it would serve as a protective amulet for the Greeks against enemies both statewide and domestic.

Among all the cruel accounts of Medusa’s dismal fate, Ovid’s is arguably the cruelest. The most renowned mythological account of her life originates from his Metamorphoses, finalized prior to his exile by Augustus in 8 CE. In this narrative, Medusa is portrayed as a beautiful young woman with radiant hair, serving as a priestess for Minerva. Minerva corresponds to Athena, the goddess of wisdom and combat; Neptune aligns with Poseidon, the deity of the sea and earthquakes; and Mercury is Hermes, the messenger god of communication.

As in much of Graeco-Roman mythology, the maiden’s beauty would prove most detrimental to her. While Medusa is attending to her duties in Minerva’s temple, Neptune, captivated by her beauty, descends from Mount Olympus and assaults her. In Ovid’s interpretation of the myth, Medusa’s story is told from the hero’s perspective when Perseus narrates Medusa’s tragic story to attendees during his nuptials with Andromeda: “Her beauty was far-famed, the jealous hope of many a suitor and of all her charms, her hair was the loveliest… she, it is said, was violated by Ocean’s lord.” Minerva, the virgin goddess, is outraged that such a desecration should occur in her esteemed temple. Upon discovering the sacrilege she refrains from punishing the perpetrator—her esteemed Uncle Neptune—and instead penalizes the victim. In Greek mythology, female victims of rape frequently endure retribution, transformation, or banishment, whereas the offenders, typically male deities, remain unpunished. This distorted justice illustrates the patriarchal principles of a society where males are often exonerated for their offenses against women.

Since Medusa was known for her luminous hair, Minerva replaces it with writhing snakes. “For Jove’s (Zeus’s) daughter turned away and covered with her shield her virgin eyes, and then for fitting punishment transformed the Gorgon’s lovely hair to loathsome snakes. Minerva still, to strike her foes with dread, upon her breastplate wears the snakes she made.” Ever a water carrier for the patriarchs, Minerva is no friend to females. The harsh sentence she imposes on Medusa, the victim, is in keeping with the perpetually hostile persona the ancient writers give Minerva/Athena toward other women.

To make matters worse, the ruthless Minerva curses Medusa to appear so hideous that she is condemned to a lifetime of turning anyone who gazes upon her into stone. Consequently, the society that once reveled in Medusa’s beauty now fears viewing her disfigurement, lest they meet their doom. Forced into a life of seclusion, Medusa evolves from a victim of divine injustice into a creature dreaded and despised by all.

Burdened with a monstrous form and condemned to isolation is insufficient punishment for this blamed victim; her head soon becomes an unwitting target in the hero’s quest for glory. To depict Medusa as more distinctly other while simultaneously extolling his heroism, Perseus describes the horror of witnessing petrified men and beasts: “And everywhere in the fields and along the road, he saw the forms of men and beasts, all turned to stone by gazing at Medusa’s face. But he, he said, looked at her ghastly head reflected in the bright bronze of the shield in his left hand, and while deep sleep held fast Medusa and her snakes, he severed it clean from her neck…” This vivid depiction highlights Perseus’s supposed bravery while emphasizing Medusa’s formidable power over anyone who dared to look at her. As in all the myths, her head became the coveted prize for the opportunistic hero during her most vulnerable state, while she lay sleeping.

Regardless of the era or tradition, symbolizing both femininity and otherness, Medusa elicits no pity, even while pregnant. Her peculiarity alienates her from humanity, making her an intrinsically perilous being that transcends the boundaries of the Greek realm. Medusa is often considered the archetypal outsider, a powerful woman from elsewhere who must be subdued. In the hyper-patriarchal and xenophobic Graeco-Roman paradigm, Medusa’s very existence is perceived as a menace that warrants elimination, as she fails to adhere to the restrictive standards of a society that esteems only Graeco-Roman women who exemplify the often contradictory ideals of beauty and chastity.

On account of the various myth traditions consistently portraying Medusa as one who resides out of their realm, could Medusa’s true roots lie outside the Greek world? In order to answer that question, it is vital to understand the connection between mythology and history. Most scholars today acknowledge that most mythology has a historical dimension. Although set in a timeless realm, myths act as a form of cultural memory preserving important historical experiences which shape group identity over generations. When we examine the myths about Medusa, it is useful to view them with a historical lens.

In the eighth century BCE, Hesiod begins the vanguard, which includes several ancient chroniclers who trace Medusa’s pre-Hellenic origins to the region that the Greeks referred to as Libya when he says: “beyond glorious Ocean at the boundary towards the night…” The Greeks defined Libya as including the entire area of North Africa west of the Nile River, extending from the Strait of Gibraltar to western Egypt and including what is now present-day Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco. Despite Greek colonization of the area referred to as Libya in the 7th century BCE, engagement and cultural exchange between the two civilizations commenced significantly earlier.

Diodorus Siculus (c. 90-20 BCE) in his Bibliotheke (Library of History) offers extensive details about Medusa’s background: “The Gorgons, they say, were a people dwelling not far from the Amazons and were ruled by women……Medusa, who was the queen of these people, surpassed her fellows in beauty and in the vigor of her body and in her ability in warlike exploits.

But she was slain by Perseus, who, after he had cut off her head, carried it with him to Greece.” Many in the academic community today argue that the Gorgons were historical Libyan Amazons and that Medusa embodied a powerful figure in a time and region marked by female dominance. Could Medusa have been a Gorgon queen, as Siculus reports, or did her impact reach beyond that, as some historians now propose? Her emblem—a female face crowned with serpent hair—functioned as a widely recognized symbol of divine feminine wisdom in the region.

In matriarchal or matrilineal religions, snake images were commonly featured in objects associated with goddess cults, underscoring their significance as symbols of fertility, rebirth, and the perpetuation of life; they were also closely linked to wisdom and female power. In his seminal book, The Power of Myth, Joseph Campbell asserts that the snake was the symbol of the regenerative powers of the feminine and “of life throwing off the past and continuing to live.” It is no accident that the reverence for snakes in female worshipping traditions is in sharp contrast to negative perceptions serpents faced in the Graeco-Roman world. The Greeks coopted the snake motif transforming the serpent into an object to be reviled instead of revered. Indeed, the horror that the ancients attribute to Medusa may arise as much from her association with snakes as from her status as an outsider and a powerful female.

Myths featuring heroes who defeat dragons, gorgons, serpents, and other so-called monstrous entities are referred to as narratives of expulsion. In these stories, the great goddesses or powerful females from indigenous religions are often depicted as terrifying figures who endure various forms of violence, including rape, decapitation, or annihilation—sometimes experiencing all three, as illustrated in the Graeco-Roman myths of Medusa. Medusa’s tragedy serves as a means of coercing a population, reflecting societal concerns and highlighting the devaluation of feminine strength. These narratives reinforce patriarchal principles by portraying goddesses as grotesque figures, undermining the complexity of feminine divinity, and reducing the great goddesses to mere symbols of danger that necessitate domination.

Medusa is not the only formidable female in Greek Mythology who hails from Libya. Frequently appearing in the Medusa myths, the patriarchal Olympian goddess, Athena, was once a powerful goddess associated closely with the region. In the pre-patriarchal tradition, Medusa and Athena were two members of a triad known as the Triple Goddess. The Triple Goddess represented the cycles of birth, death, and rebirth, this tradition also included Metis, or Neith, who signified the nurturing aspect of the goddess; Athena, who embodied the maiden warrior; and Medusa, who symbolized the destroyer, or underworld, aspect of the Triple Goddess.

This trio from Libya highlights the cultural relationship between the Libyan and the Greek spiritual traditions, illustrating how ancient goddess worship was reshaped—and routinely weakened—by the invasion of patriarchal systems. Time and again, the Greeks— influenced by pre-Hellenic traditions—assimilated indigenous goddesses, resulting in the formulation of new myths that diminished these formidable female figures to subordinate roles as wives, sisters, and daughters, and in the case of Medusa, a monster.

Even so, time has been kind to Medusa. Her odyssey illustrates a transformation from a once-revered goddess of an indigenous population to an oppressed figure condemned within the patriarchal Graeco-Roman tradition. Ancient writers might be surprised to learn that nowadays Medusa’s name and image are easily recognizable, even to those who are not well-versed in Greek mythology. In contrast, the hero of the story often remains overlooked, with his name and background frequently disregarded. Medusa, like the goddess tradition she once embodied, has been reborn and has returned to her original form. Today, she serves as a symbol of female empowerment and is a global cultural icon, inspiring others to challenge the narratives imposed upon them.