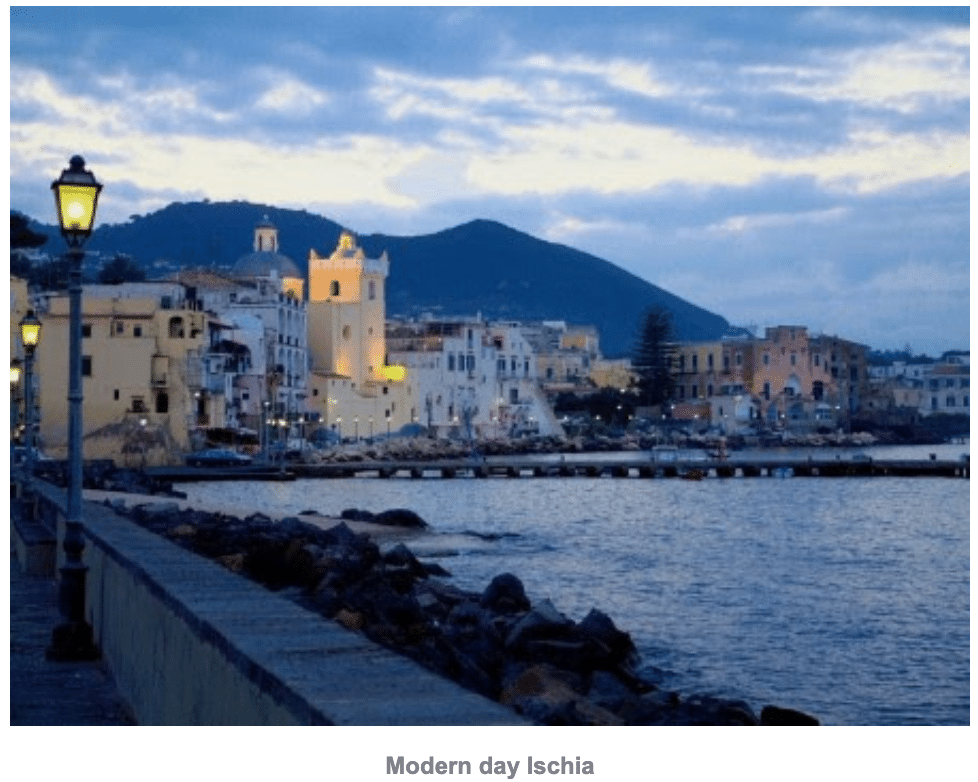

Home to thermal springs and verdant landscapes, the idyllic island of Ischia also houses the first Greek settlement in all of Europe. Enterprising pioneers from the Greek island of Euboea, founded the colony in the mid-eighth century BCE, naming it Pithecusae from the Greek word pithekos meaning “ape” or “monkey.” But why was the island named for monkeys? Situated in the Bay of Naples, Pithecusae was never inhabited by apes or monkeys, leading some scholars to speculate that its name may come instead from the Greek word pithekizo which meant “to monkey around.” Another thought is that this term was used derisively by mainlanders to refer to the speculative and profiteering islanders who originally hailed from the Athens environs, over seven hundred miles away.

Which begs the question, why on earth would settlers from Euboea, a sea-faring island to the east of Athens, be interested in colonizing what was then the westernmost boundary of the Mediterranean? In order to answer this question definitively, it is important to understand what was occurring in ancient Greece at the time. Never known for its arable land, the farmland shortage became pronounced during the population explosion of the Archaic Age. It was from the eighth through the sixth centuries BCE that colonizing other lands became fashionable to the intrepid ancient Greeks.

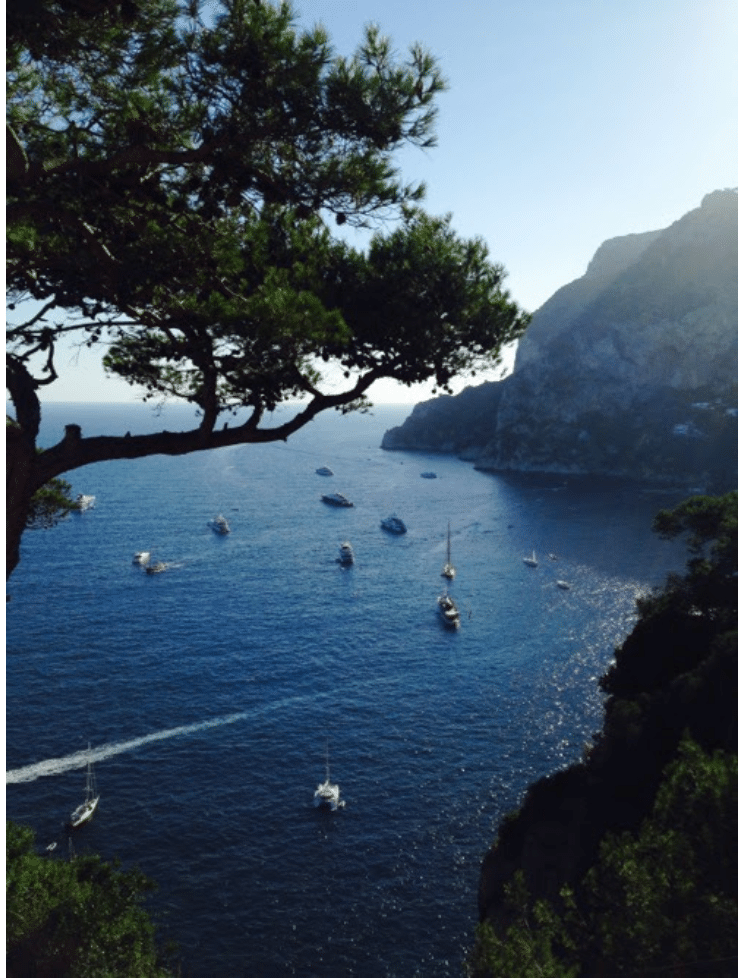

Although the rich fertility of Pithecusae’s volcanic soil was desirable to the Euboean settlers, more alluring to the Iron Age colonists were its ample iron ore reserves. In the eighth century BCE, iron was the new bronze and the adventurous settlers were willing to travel far and wide for their current metal of choice. Because of its protected, well-positioned harbor along with its vast resources, trade networks were bountiful in Pithecusae. The island traded heavily not only with their mainland neighbors of Campania, Apulia, Etruria and Latium but also with the Near East and Carthage, amongst others. Throughout Greek settlements, Pithecusae was recognized as having the widest-range of objects from the farthest reaches of the Iron Age Mediterranean.

Today, chief among Pithecusaean objects of interest is a seven-inch cup, originally made on the island of Rhodes and dated to around 750 BCE. Battered and diminutive, at first glance this artifact is unimpressive, but upon closer inspection an engraving can be found that has sparked no small amount of interest in the academic community. The etching, believed to have been scribbled in Pithecusae around 725 BCE, is not only the earliest example we have of Greek writing, more compelling still is that this is the first example we have of Greek poetry! Two of the three lines of text are in Homeric hexameter and refer to Nestor, a character from Homer’s Iliad:

“I am Nestor’s cup, good to drink from. Whoever drinks this cup empty, straightaway Desire for beautiful-crowned Aphrodite will seize him.”

Ironically, the earliest recorded evidence we have of Homer’s epic hymn is in the form of a joke. Both as a pun demonstrated by its modest size as in The Iliad Nestor’s cup was notorious for being too heavy to lift; and as a bawdy quip as the reference to Aphrodite bespeaks. That eighth century Greeks living on the edge of Magna Graecia could jest about the Homeric legends testifies to how deeply ingrained, even prosaic, Homer’s narratives must have been. Undeniably, The Iliad was originally composed as an oral hymn, to be sung or recited, possibly as early as 1200 BCE with its written format believed to have been penned anywhere from 725 BCE to 634 BCE. As a result of the discovery of the etching on this obscure cup in the backwaters of ancient Greece, some scholars now argue that the date of Homer’s poem must be pushed back for knowledge of his verses to be as common as this cup attests.

Sadly, in contrast to its amusing engraving this cup has a more sobering epilogue; it was discovered in the grave of a ten-year old boy offered by his father in a funeral pyre. Doubly tragic is that the young lad, who was in death its final recipient, would never know the adult delight the cup’s inscription signified. The somber conclusion of this cup’s destiny is a reminder that in the Greek world omnipresent death was humor’s dark companion.

Which brings us to the fate of Pithecusae; in a land of firsts with a population boasting ten thousand at its zenith in 700 BCE, why was this plucky Greek settlement not better known? While it was the rich volcanic soil that initially lured the Greeks to settle the island of Pithecusae, the reason for its demise lies also in the soil’s combustible origins. According to geographer and historian Strabo (64 BCE to 24 CE), severe volcanic and earthquake activity impacted Pithecusae’s acclaim leading one classical scholar to term it “the lid of a cauldron.” Indeed, due to its geological volatility, an exodus ensued and Pithecusae’s bustling trade was eventually transferred to the nearby Greek settlement of Cumae on the southern Italian mainland. Most historians agree that by 500 BCE the settlement of Pithecusae was all but destroyed by a volcanic eruption of Mount Epomeo, the island’s largest volcano. Perhaps in a fitting Homeric denouement, the fiery fate of Nestor’s Cup foreshadowed the incendiary collapse of the once burgeoning land from which it sprung.

Published on Classical Wisdom