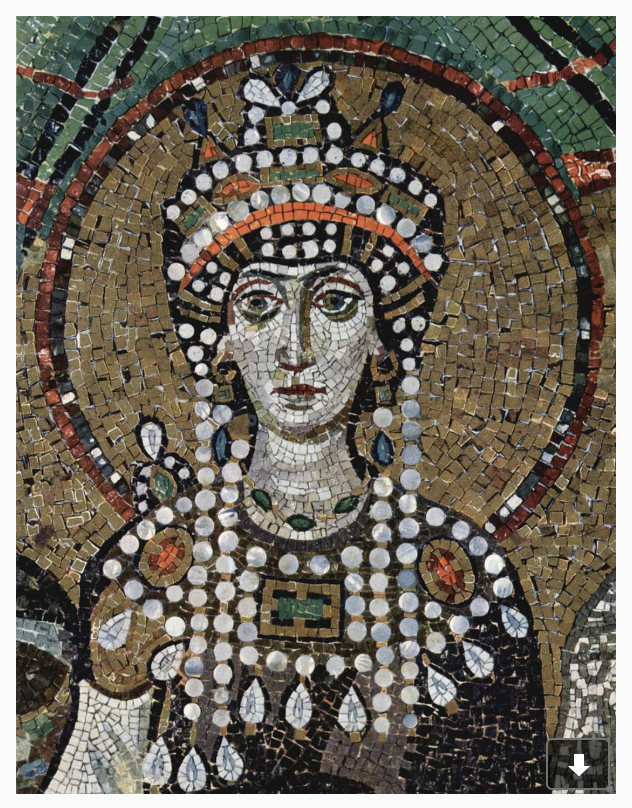

When we consider the pious lives of saints, images of self-sacrificing martyrs come to mind, devout adherents passionately immolating themselves for a higher cause. So it may come as something of a surprise that joining the haloed ranks is the ambitious, resolute, and oftentimes controversial, Byzantine Empress Theodora (c 497-548). To be sure, in February of 2000, over fifteen hundred years after her birth, Theodora was beatified by the Patriarch of Antioch—head of the Universal Syrian Orthodox Church—a church the empress helped found. What role did this scintillating, frequently contentious woman play in the religious practices of the era? Moreover, can Theodora’s devotional influence still be felt in the region to this day? To answer these questions it is important to understand the breach within the Christian church during Byzantine times.

It all began when a rift occurred in the Christian church when at the behest of Pope Leo the Great (c 400-461), the Council of Chalcedon (451) ruled that Christ had two natures, human and divine. Supporters of this edict became known as ‘Chalcedonians.’ In direct opposition were the Monophysites, represented by various Patriarchs primarily in the East, who had long argued that Christ had only one nature—divine. Interestingly, this doctrinal divide was as much regional and cultural as it was religious. Encompassing the Greco-Roman world, much of the Western part of the Byzantine Empire agreed with the Roman Pope and considered itself Chalcedonian. Whereas, in the East—especially in ancient strongholds like Egypt and Syria—Christians were predominantly Monophysites.

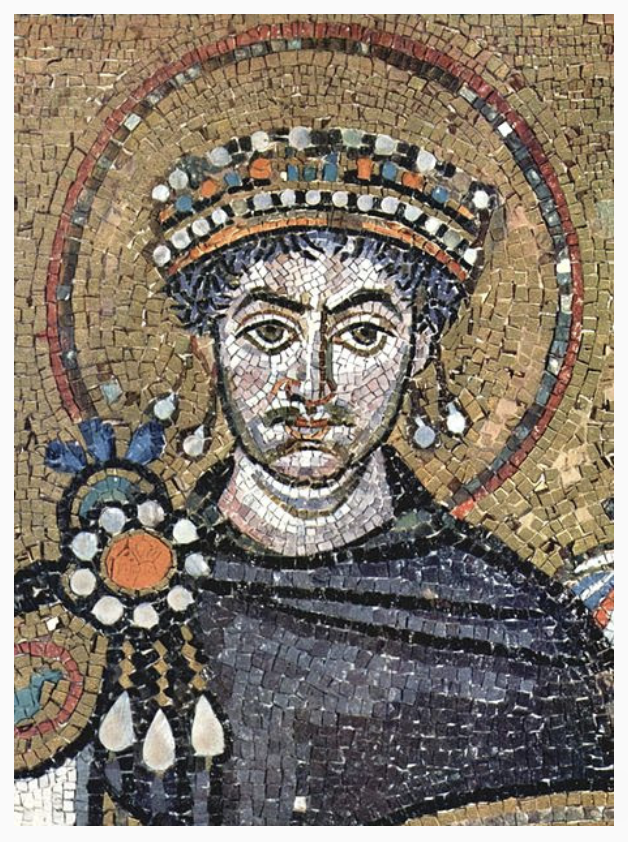

But which side of this theocratic argument did Theodora support? Although Theodora is thought to be of Syrian origin, she did not convert to Monophysitism until after meeting Patriarch Timothy of Alexandria who is credited with having a profound influence on her life. Shortly after her conversion she returned to Constantinople and—in an interesting switch of professions—left her life as a prostitute-courtesan to become an unassuming wool spinner. But as fate or the heavenly powers would have it, while working as a wool spinner Theodora met Justinian (c 483-565) who soon fell under her spell. Ever resolute, Justinian’s support for the Chalcedonians did nothing to quell Theodora’s enthusiasm for her beleaguered faction.

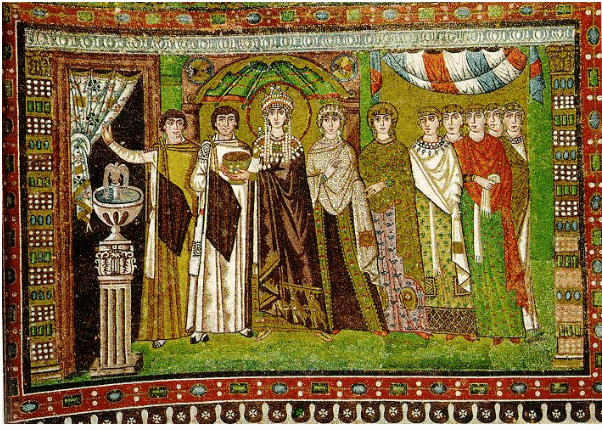

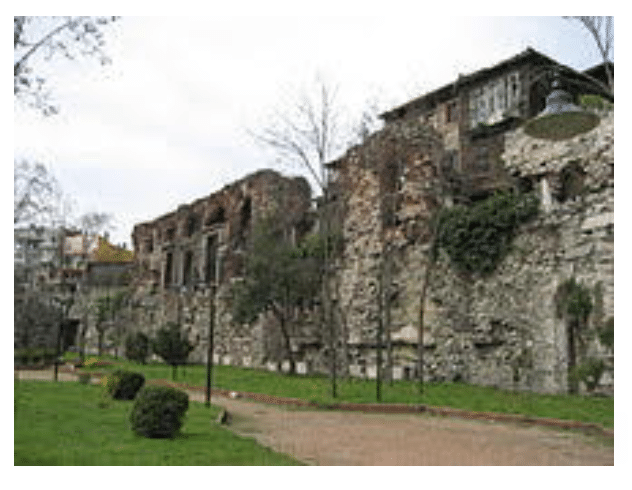

Because the Monophysites were often persecuted within the orthodox Byzantine Empire, Theodora became their vehement advocate providing shelter for the covert clergy within the Hosmisdas (or Boukoleon) Palace complex. Over time the complex came to include the Church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus (extant today and known as Küçük Ayasofya Camii), which was adapted for monastic living in order to accommodate the hundreds of religious refugees housed there. An inscription surrounding the nave of the church reads: “…increase the power of the God-crowned Theodora whose mind is adorned with piety, whose constant toil lies in unsparing efforts to nourish the destitute.” It is believed that over several hundred of the persecuted clergy at one time or another lived under Theodora’s protection. Moreover, to make the Hosmisdas more accessible to the empress, in 532 a passage was constructed leading from it to the imperial Great Palace, which housed the royal couple.

For as much as Theodora was committed to her faction, uniting the two disparate faiths became Justinian’s unrealized dream. In spite of his desire to unify the church (or perhaps because of it), Justinian chose to look the other way when it came to his wife’s activity on behalf of the clandestine Monophysites. Aside from providing shelter and contributing vast resources to the besieged group, Theodora was responsible for founding a Monophysite church in Antioch called the Jacobite Church.

Its namesake—Jacob Ba’adai—had been sheltered in a cell for fifteen years at the Hosmisdas Palace. However, once Jacob was ordained bishop he was responsible for both organizing clergy and ordaining priests and as such had to leave the confines of the palace sanctuary. Because the imperial police were hot on his trial, Jacob became adept at avoiding them by assuming disguises. His surname Bar’Adai (meaning course horse cloth in Syriac) was given to him because of his run-down costume as a mendicant. Jacob would go on to become one of the greatest missionaries of all time and ordained thousands of priests, deacons and consecrated scores of bishops in a church that would ultimately become the Universal Syrian Orthodox church.

In hindsight it seems that in regards to religion, Justinian and Theodora were often at cross-purposes. While Justinian wanted to mend the split between the Chalcedonians and the Monophysites, Theodora’s powerful intervention contributed to the resolve of the oppressed Monophysites further deepening the divide. Over the years many historians have speculated that Theodora’s fierce advocacy on behalf of the Monophysites may have weakened Christianity’s overall message, especially in the East where the Monophysite presence was extensive. They argue that Monophysitism might have died an early death if not for the considerable intervention of Theodora. Did Theodora unwittingly weaken Christianity’s message in the East perhaps opening the way for the spread of a new religion in the region? It must be remembered that only a span of fifty years separates the death of Theodora and the birth of Mohammed. Indeed, Christianity’s lack of cohesion—for which Theodora played a role—may have been only one of several factors encouraging the expansion of Islam in the region.

Undoubtedly, Empress Theodora was much more than meets the eye. Abundantly supplied with material qualities like beauty, brains, and ambition, it is compelling to discover that Theodora had an ethereal side as well. As with her strident advocacy aiding the less fortunate, in her piety Theodora never lost sight of her humble beginnings and would often attribute the grand trajectory of her life to her dedicated devotional practice.

Published on Classical Wisdom