Thesmophoria, the feminine fertility festival, dedicated to the Goddess Demeter, was literally for women only. Citizen males of ancient Greece were unconditionally restricted from attending any portion of the three-day long event known as the Thesmophoria, though they were responsible for its expenses. Further, men who spied on, or interrupted, the Thesmophoria were subject to life threatening and disfiguring acts of violence perpetrated by the Thesmophorians themselves.

There are some noteworthy examples demonstrating this extensive retribution, straight from ancient sources. First there is the lore that the hapless King Battos of Cyrene—famed for founding Cyrene—was cruelly castrated by the furious disciples for surreptitiously observing their sacred and secret rites.

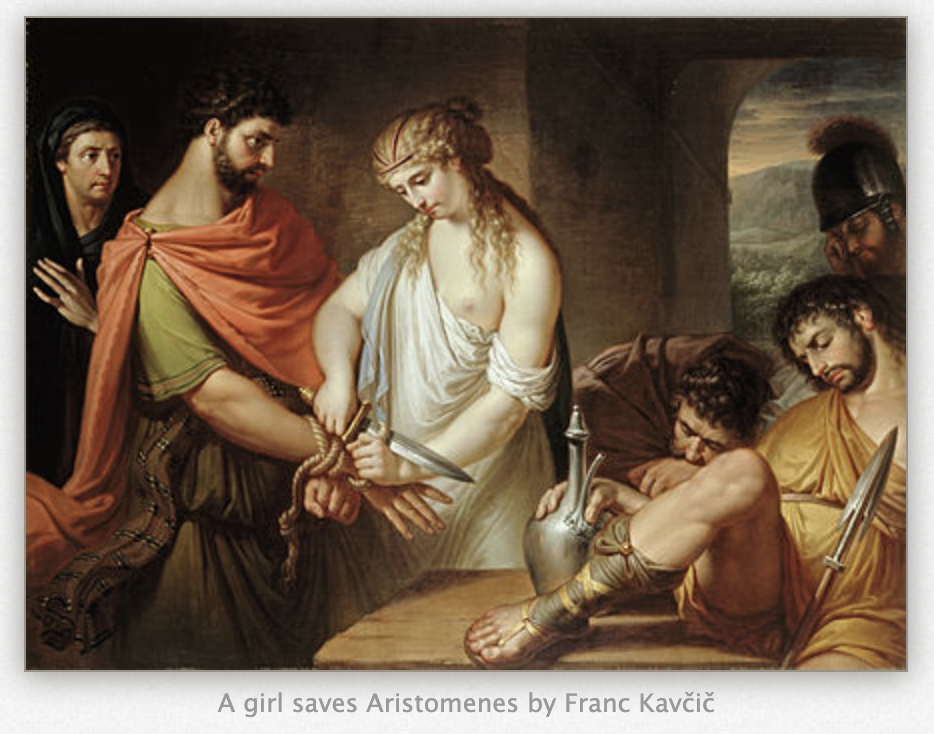

Then there is the tale related by Pausanias (110 CE- 180 CE) of the legendary Messenian hero Aristomenes, who was celebrated for his victories with the Spartans. Unfortunately, he did not fare as well against the women of the Thesmophoria. He happened upon the pious women in the midst of their clandestine celebration, only to be “knocked senseless” by their sacrificial knives and spits.

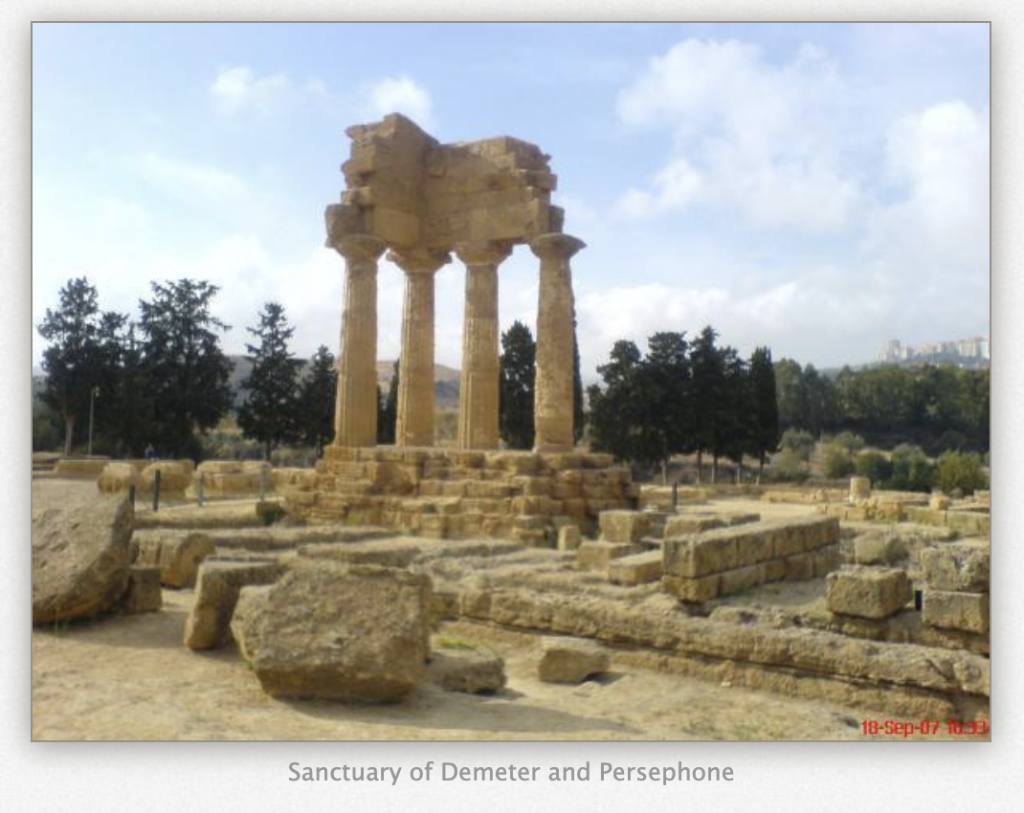

Next, there is the legend of unlucky Militiades, who, while in battle to secure the island of Paros, leapt over the wall leading to the Thesmophorian shrine. Once there, he was so overcome with terror that in jumping back over the wall he sprained his thigh, from which he developed gangrene and later died. Herodotus (484 BCE- 425 BCE) recounts this as an admonishment and warms that this mournful outcome was due to his breaching the sacred sanctuary of Demeter Thesmophoros.

Then we have Plutarch’s (46 CE- 120 CE) narrative of Pesistratus (562 BCE -527 BCE), the tyrant of Athens, and the Athenian statesman Solon (638 BCE-558 BCE). While the female adherents were celebrating in the Megara, the two leaders pulled a trick on them by enlisting two beardless men to impersonate the disciples.

Once discovered, the Thesmophorians brutally attacked the wretched mimics.

Finally, there is Aristophanes’ comedic satire Thesmophoriazusae or “Women of the Thesmophoria.” In it, Aristophanes casts his colleague Euripides as the character for whom the Thesmophorians want revenge.

“Today at the Thesmophoria the women are going to liquidate me, because I slander them,” cries Euripides.

The premise is that the rebellious disciples seek to kill Euripides for characterizing women in his plays as villainous. While the women are mocked in terms of their democratic assembly and their ritual, Aristophanes’ depiction of the Thesmophorians as uncontrollable and violent is in keeping with the androcentric mindset towards the festival.

The brutality of these stories demonstrates that men’s profound uneasiness with the Thesmophoria was in direct proportion to their wary respect for it. Though suspicious, pious citizen males could not obstruct it, as it was deemed both holy and integral to the health and well-being of the polis. Indeed, the citizen males considered the Thesmophoria to be at once both threatening and reverential. Why else, but for the power to increase fertility, would the males in patriarchal ancient Greece comply with the wishes of the obviously inferior sex? In a society where men set the rules, the Thesmophoria turned the dominant paradigm on its head.

Kept from all activities in the public sphere, citizen wives were only granted a watered-down citizenship, which simply allowed them to bear citizen males. Disenfranchised from participating in the political life of the polis, women were similarly as powerless in any acts of societal sacrificial violence. For example, women usually had no access to instruments of sacrifice such as the all-important knife, kettle or the spit. However, archaeological and literary evidence suggests that full-grown sows, killed in a sacrificial manner employing a knife, were discovered at various Demeter sanctuaries throughout Attica.

Indeed, most scholars now concur that the Thesmophoria was unique in being one of the only feminine festivals where sacrifices were performed, meaning that the women of the Thesmophoria had rare access to the violent instruments of death.

Meeting outside the androcentric social constructs of family; the disciples were at liberty to become autonomous individuals without concerns for their family, as they once were in pre-patriarchal times. It also empowered a united feminine community without male restrictions—a possibly dangerous and subversive combination for the dominant male culture of ancient Greece. Indeed, enfranchised men were afraid of the anger of the subjugated female. And they should have been – for the women at the Thesmophoria, independent and armed at their secret cult festival, were a force to be reckoned with.

The original publishing can be found at Classical Wisdom