Agrippina, Julian-Claudian Empress

The ancient chroniclers would have us believe that Julia Agrippina the Minor better known as Agrippina the Younger (16 CE-59 CE) was a regicide, a perennial poisoner, a murderer, an incestophile, a seductress, and a detestable profligate. Indeed, some of her crimes were so heinous they would put a blush on the sallow cheeks of Lady Macbeth. But are the accusations true? Agrippina was the great-granddaughter of the Divine Caesar Augustus (63 BCE- 14 CE) and sister, wife and mother of the three final Julio-Claudian emperors. She was the first ever living Augusta and both an empress and a co-regent in her own right. In a time when ambitious women were considered beneath contempt, how could a woman who exercised power by proxy get fair treatment from the ancient historians? Who was Agrippina the Younger and why do stories of the depths of her depravity encircle her to this day?

We know Agrippina the Younger, primarily through the myopic lenses of three ancient chroniclers: Tacitus (56 CE-120 CE), Suetonius (69 CE-122 CE) and Cassius Dio (155 CE-235 CE). These three historians wrote during the reigns of emperors who were hostile toward the Julio-Claudian clan anywhere from fifty to two-hundred years after she died. The credibility of these three men is the question that plagues their outrageous claims about Agrippina. In addition to being deeply misogynistic, it was acceptable for historians in ancient Rome to be biased and moralistic. For example, unless they are demure and retiring, in his Annals, Tacitus—the most prolific of the three—seldom says a kind word about women and tells us that the country was transformed when Claudius married Agrippina: “Complete obedience was accorded to a woman.” he huffs.

He is also prone to reading his subject’s minds. What perception! Likewise, Suetonius’s Lives of the Caesars –when he mentions women at all—relies on rumor for many of his narratives seldom distinguishing word of mouth from actual facts. While equally hostile to women, Cassius Dio’s Roman History also has a pronounced bias against the Julio-Claudian clan in particular, and comes to us in fragments that have been redacted from Byzantine monks in the Middle Ages. Besides these primary three, another source that crops up from time to time is Pliny the Elder (23 CE-79 CE) who was more or less a contemporary of Agrippina.

However, his interest was in natural history as opposed to the imperial variety so unless it is something by way of nature (breech birth, double canine teeth, etc) he seldom writes of Agrippina. So, how can we know the woman who was Agrippina? Perhaps understanding some of the distortions in the narratives spun by these ancient chroniclers may enable us to see her more clearly.

……………………………

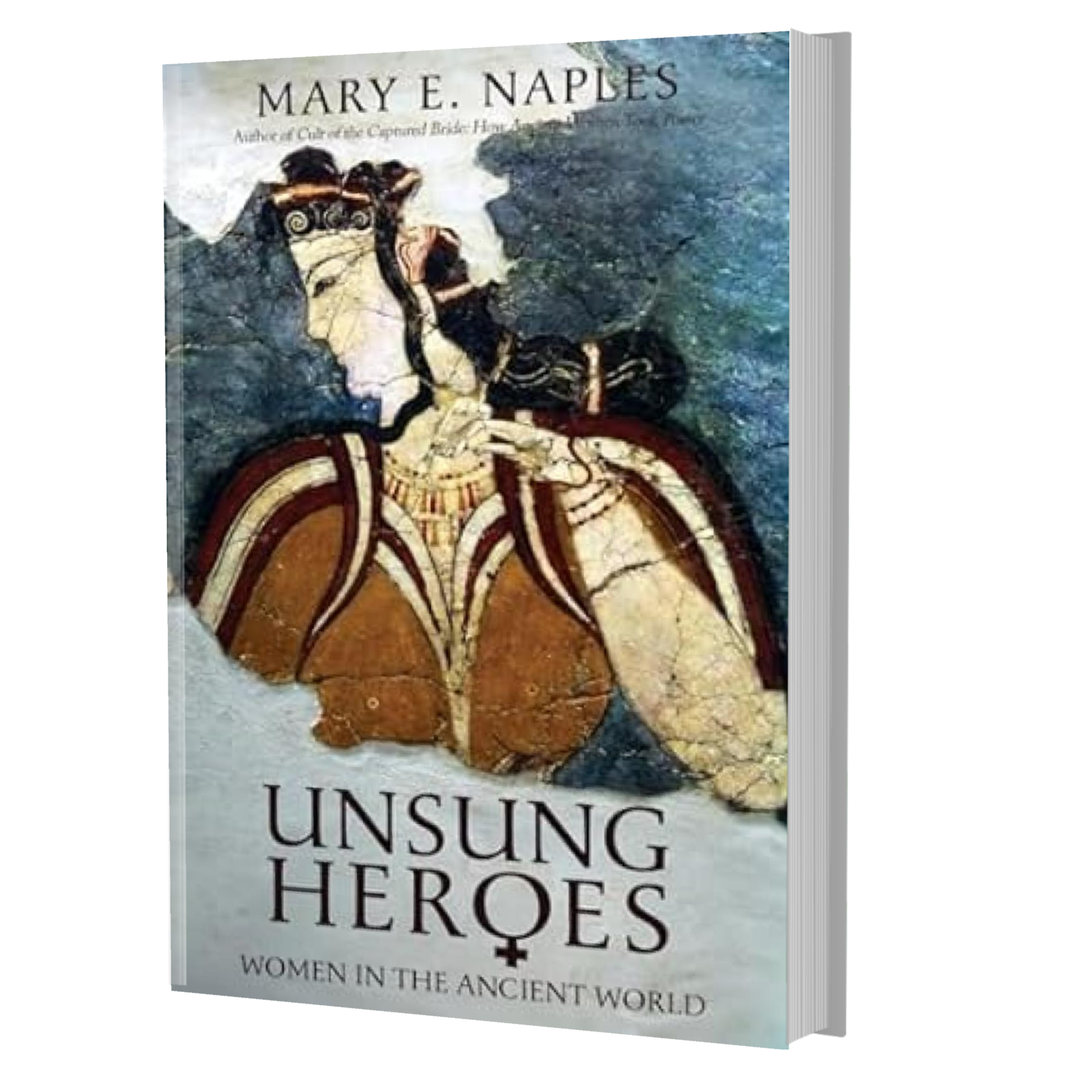

Was Agrippina the harridan the ancients say or was she an effective leader? Find out in my book Unsung Heroes on Amazon.

Love this! Super talented Mary!