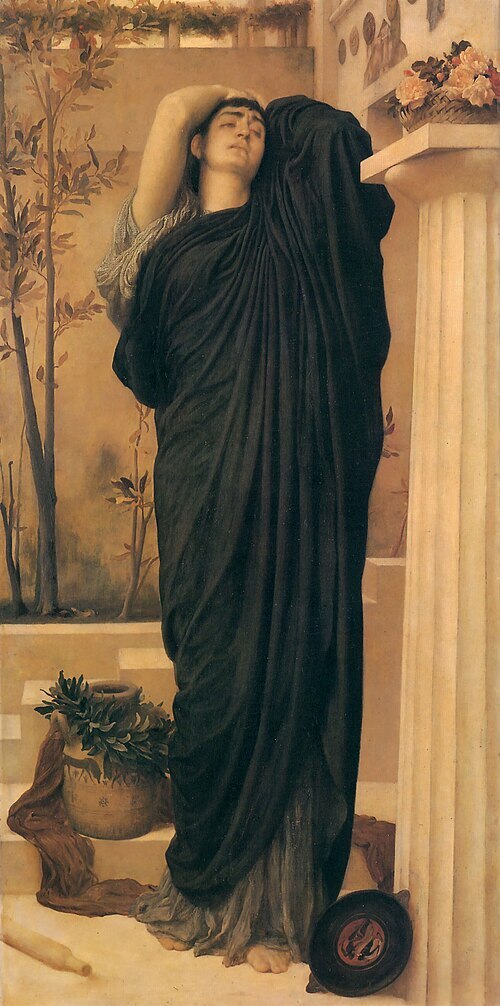

Not every Greek character has a complex named in their honor, and few are more deserving of such recognition than Electra. Coined by Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung to name a female counterpart to Freud’s famous “Oedipus Complex”, the “Electra Complex” describes a daughter’s longing for her father, coupled with deep resentment towards her mother. This term effectively encapsulates the myth of Electra, the princess of Mycenae and the second daughter of King Agamemnon and Clytemnestra. Imbued with themes of vengeance, loyalty, and the complex dynamics of familial relationships, her story resonates profoundly in Western literature and psychology.

After King Agamemnon was killed by his wife Clytemnestra upon his victorious return from the ten-year long Trojan War, Electra helps spur her brother Orestes into seeking vengeance for their father’s death by killing their mother. Her profound animosity toward her mother stands in stark contrast to the deep devotion she holds to the memory of her slain father.

But how does Electra conform to patriarchal values, while also challenging traditional feminine stereotypes through her heroic behavior and motivations? By subverting the ancient Greek ideal of submissive femininity, Electra embarks on an obsessive quest to avenge her father’s death, ultimately leading her to lose sight of what it means to be human.

Electra is most fully depicted in the works of the three Greek tragedians—Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides—where she plays a pivotal role in her family’s tragic saga. As the first to introduce Electra, Aeschylus is also the first to burden her as the avenging daughter in The Libation Bearers, the second play of the Oresteia trilogy, where he conceives a narrative that both Sophocles and Euripides would later emulate. Halfway through The Libation Bearers, however, Electra disappears; thus, her character lives more fully in the eponymous works of Sophocles and Euripides.

Among the latter two tragedians, Sophocles offers the most vivid depiction of Electra in his titular play, rendering it the most frequently performed, translated, and studied version of her narrative. The psychological complexity and heroic nature of Electra’s suffering make the play a dramatic centerpiece, often overshadowing Aeschylus’s earlier work and Euripides’ eponymous play, which is frequently viewed as a critique of it.

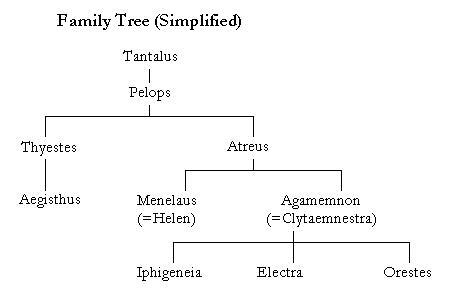

Homer, or the poets known as Homer, introduced the foundational elements of the tragic narrative of the House of Atreus in the Odyssey during the 8th-7th century BCE, but it was Aeschylus, with his Oresteia trilogy, who is considered the standard bearer of a family saga that has endured throughout the millennia.

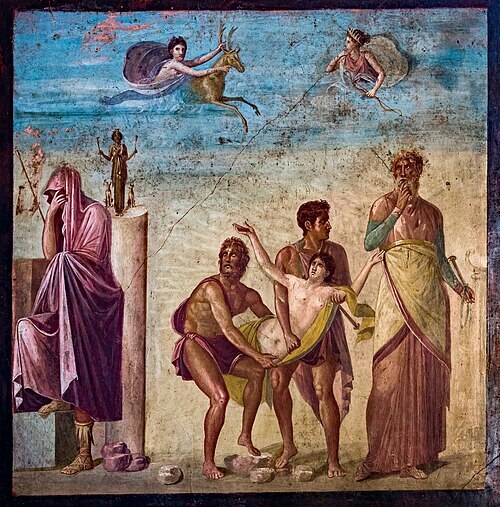

In the Oresteia, the action that precedes the primary narrative is as important as the story itself. With calumny heaped upon Clytemnestra throughout the ages, it is important to know that this villain was once a victim herself. In fact, if Agamemnon had not boasted that he was a better hunter than Artemis—the goddess of the hunt—their eldest daughter, Iphigenia, might have lived to see old age. But as it turns out, Artemis was enraged by Agamemnon’s hubris and stymied the winds, causing the Greeks to be stalled at the Bay of Aulis and unable to launch their attack on Troy. Only by sacrificing his eldest daughter in her honor would Artemis release them. Faced with a choice of certain defeat at Troy or filicide, the ever-vainglorious Agamemnon chose to sacrifice his daughter: her life the price for victory.

On the promise of a betrothal to the most eligible bachelor in the Greek world—the semi-divine war hero, Achilles—Agamemnon lures Iphigenia and Clytemnestra to Aulis. In the Greek world it was standard practice for a father to bargain with his future son-in-law without the knowledge or consent of either mother or daughter; thus, his request was not unusual. Enthusiastic about the match, Clytemnestra and Iphigenia traveled to Aulis posthaste.

One can imagine Iphigenia’s excitement as she walks down the aisle eagerly anticipating meeting her handsome betrothed. But instead of seeing Achilles at the altar, she faces the horror of her wild-eyed father wielding an ax:

“My father, father!” she cries while he bellows to his henchmen: “Hoist her over the altar like a yearling, give it all your strength, she’s fainting–lift her, sweep her robes around her…here gag her hard, a sound will curse the house.”

Treating her with no more regard than he would a sacrificial goat, alas, Iphigenia is even prohibited from screaming lest another curse fall on the cursed House of Atreus. Barbarous and cruel, Agamemnon takes more care in safeguarding his dynasty than in protecting his child. The sheer brutality of the act renders the chorus speechless. Eager to put the gruesome episode to rest, Agamemnon removes all traces of his daughter, affording her no funeral rites as she quietly slips away from the story—unlike her mother’s wrath. The savage slaying of her daughter unhinges Clytemnestra, who vows revenge against her husband.

In the first play of the Oresteia trilogy, titled Agamemnon, a decade has elapsed since the horrific act. Although Clytemnestra had ample motivation to kill him, Agamemnon’s return from the Trojan War brought with it a fresh grievance: among his spoils was a war bride, the Trojan princess and prophetess Cassandra, fueling Clytemnestra’s already incendiary flames.

Following his victorious homecoming, Clytemnestra ensnares Agamemnon in royal attire and lures him into a bath, where she mortally wounds him, finally avenging the sacrifice of their daughter. Agamemnon’s murder, however, results from a collaboration between Clytemnestra and her lover (and Agamemnon’s cousin) Aegisthus, who seeks justice for the atrocities committed by Agamemnon’s father, Atreus, against his brother (and Aegisthus’ father), Thyestes. In a gruesome feast, Atreus fed Thyestes the flesh of his children. After Agamemnon’s death, Aegisthus rules as king with Clytemnestra by his side as queen; the chorus concludes the play by urging Orestes, Agamemnon’s son, to exact revenge for his father’s murder.

When Sophocles begins Electra, Orestes has returned to Mycenae after a twenty-year exile to avenge his father’s murder and reclaim the throne. Guided by the god Apollo, Orestes keeps his return secret–even from his sister. He disguises himself and instructs his servant to announce his fake death to the palace.

Meanwhile, as if time itself were suspended, his sister Electra is in deep mourning, overwhelmed with an all-consuming grief and a profound desire for retribution for her father’s murder. Her suffering feels so immediate that the audience might be forgiven for thinking Agamemnon’s death was recent and not an event that occurred nearly twenty years ago.

“I shall never end my dirges, and bitter laments while I still see the twinkling, all-radiant stars and the daylight…Come to me succour me, punish my father’s murder most foul.”

Electra basks in her misery disproportionately; her emotional intensity crosses the boundaries between the human and the divine. Even the chorus rebukes Electra, saying that her “dirges and prayers” cannot bring the dead back and that her grief “offers no release from suffering’s chains.” They continue by asking why she “courts such senseless anguish.”

Throughout the play, Electra exhibits an uncompromising and monomaniacal nature which serves as the driving force to avenge her father’s untimely death. A single woman without male protection, she is deemed powerless and incapable of killing Clytemnestra and Aegisthus on her own. In Greek society, women were perceived as weak and insubordinate, relegated to the domestic sphere, they lacked the authority necessary to enact revenge which was in the male realm. Despite Electra’s fierce resolve, she must rely on Orestes to take action; only a male avenger can restore their father’s dignity in a manner that society considers just.

Waiting for Orestes, Electra is vaguely Penelope-like: “Oh, I am sick and weary, weary of waiting for Orestes to come back home and end all this.” But waiting is where the resemblance to the over-accommodating Penelope ends. In her quest for authority, Electra embodies traits of her heroic father, yet she is also her mother’s daughter. Like Clytemnestra, Electra is a subversive female figure seeking vengeance for a perceived wrong, but as alike as mother and daughter are in their male-like fervor, they are at cross purposes.

Through her steadfast loyalty to her father, Electra prioritizes his honor over that of her mother and deceased sister. By identifying herself with the male members of her family, she reinforces the Greek ideal of family hierarchy, where paternal lineage and male-led revenge dominate. In contrast, Clytemnestra embodies fierce maternal protectiveness, drawing from pre-patriarchal archetypes like Demeter—-goddess of the harvest. She represents a powerful queen who values mother-daughter bonds over patriarchal hierarchy and male lineage. Clytemnestra reminds Electra that her father’s murder did not occur without provocation; he acted savagely toward her sister: “This father of yours had the brutality to sacrifice his daughter.”

Despite Electra’s significant rhetoric throughout the play, it consistently serves the interests of the males in her family; she never once mentions her sister Iphigenia’s wrongful death. Similarly, Electra’s fixation on the murder of Agamemnon mirrors Clytemnestra’s focus on sacrifice of Iphigenia.

However, Clytemnestra seems to have only maternal feelings for her deceased daughter and not for her son, Orestes. When she receives the false news of Orestes’ death, Clytemnestra is ostensibly relieved: “He never saw me again, he only accused me of killing his father and sent me terrible threats…but now today I am free, free from fear, fear of him.”

Contrastingly, Electra wails in despair when she hears the news of Orestes’ death: “The death of me!” followed by “My hopes are lost, the only relief I had, lost with my noble brother.” With all the male members of her family now gone, Electra is expected to be powerless but her temperament resembles that of a male, illustrated when she later speaks to her sister, Chrysothemis: “You mustn’t flinch. Your sister needs your help to kill Aegisthus—the man who perpetrated your father’s murder.”

Despite societal expectations of her gender, Electra resolves to act the part of a hero: “Then think of what people will say if you follow my plan. What glory you’ll win for yourself and for me! When our fellow townsmen or strangers see us, they’ll acclaim us with words and praise like these.”

In ancient Greece, women were not expected to attain greatness; fame was reserved for males. Chrysothemis, however, is a culturally appropriate Greek woman, thus restrained and circumspect: “Why are you putting on this audacious front and calling on me to follow? Don’t you see? You’re not a man, but a woman. You haven’t the strength to conquer your foes.”

The scene with Electra’s sister is reminiscent of the scene with another Sophocles’ heroine, Antigone. When Antigone seeks her sister Ismene’s assistance to bury their brother, she is unsuccessful. The exchange between the two sisters ends similarly, with Electra, like Antigone, labeling her sister a coward, asserting that death is preferable to a life devoid of purpose, and declaring her intention to proceed alone.

It is not long after that brother and sister are reunited. In fact, it is fully two-thirds through the play that Electra and Orestes finally meet. When she first encounters him, Electra believes her brother to be a messenger carrying her dead brother’s ashes. To test her loyalty, Orestes does not tell her his identity straight away. After much back and forth about her life with her father’s murderers, “who force me to be their slave,” at long last Orestes reveals himself to her. When she is skeptical, he gives her proof: “Look at this ring with our father’s seal. Do you believe me now?” For once in the play, Electra is overjoyed: “Darling brother, I’ve heard the voice I never even hoped to hear.”

The two siblings are a study in contrasts. Unlike Electra, who dominates the dialogue with her lengthy laments and verbal clashes, Orestes is taciturn, speaking only about 200 lines compared to her over 700. While Electra is overly emotive throughout the play, Orestes remains stoic and composed, rarely displaying any emotion. Even in the final scenes, where he kills his mother and Aegisthus, he shows little passion, underscoring his role as a man of action rather than of words.

Orestes arrives on the scene with a precise plan for revenge, which he executes effectively in an almost detached manner. Conversely, Electra is the moral compass who sets the emotional fervor of the play but has no plan and is not directly involved in the killings. She inspires the action of which Orestes is the instrument.

As she is for much of the play, Electra is outside the palace when she initially encounters Orestes. The very act of being outdoors is considered transgressive for women. In ancient Greece, women were expected to remain indoors at all times, to cover themselves with veils, and to maintain silence, as illustrated by the Athenian proverb, “Silence is the adornment of the woman.” At every turn, Electra challenges societal conventions.

At this point, Orestes’ plan for revenge is ready to be set in motion. The reasoning behind the reports of Orestes’ false death is that it enables him and Pylades—his steadfast friend and ally—to infiltrate the palace under the pretense of transporting Orestes’ alleged remains. Their entrance into the palace sets the stage for Clytemnestra’s murder.

Clytemnestra’s death appears behind the scenes adhering to a strong convention in Greek tragedies where most acts of violence occur offstage. As Orestes enters the palace, Electra remains outside. She reacts to Clytemnestra’s anguished cries while the matricidal Orestes remains silent: “My son, my son! Have mercy on your mother!”

Electra responds: “You had no mercy on him.”

Clytemnestra then cries out, “O moi! I am struck!”

In retaliation, Electra yells, “Strike her a second blow, if you have the strength!”

Shortly after the heinous act, Aegisthus enters the palace to view the body of the supposedly deceased Orestes. Posing as Orestes’ courier, Orestes guides him to the spot where the infamous couple murdered Agamemnon. When Aegisthus lifts the mantle, he discovers not the deceased Orestes, but the deceased Clytemnestra instead: “Oh god, what is this?… I’m caught in a trap.” Then “Please! Allow me a word–just one!”

Remaining outside the palace still, Electra reacts to his cries: “Kill him at once: kill him, and then throw his corpse for the dogs and birds to bury out of sight…”

In her overarching quest for revenge, Electra loses her humanity transforming herself from a heroine akin to Antigone into Antigone’s adversary, the overly rigid King Creon, infamous for denying Antigone the right to bury her brother.

The chorus concludes the play with a morally ambiguous statement: “O seed of Atreus, how much you have suffered! But now this attack has forced you out into freedom. You’ve come to the ending.”

Vengeance has been achieved, but will the recent murders put an end to the House of Atreus’s relentless cycle of revenge? The audience is left to draw its own conclusion. There is no deus ex machina descending from the heavens to provide moral clarity to this unresolved conclusion. In contrast to the other two Electra plays, where Orestes faces divine retribution from the Furies or expresses regrets for his actions before encountering a vision of cosmic order, Sophocles’ work emphasizes the perpetual cycle of blood vengeance, examining its futility and the price it exacts on both the avenger and the avenged. The ending deliberately feels empty, their “victory” hollow, suggesting another act (or another play) is needed for completion.

But perhaps that is exactly how Sophocles wanted the audience to feel.

Inside the House of Atreus, each cycle of vengeance claims to seek justice, which leads to yet more bloodshed. By highlighting Electra’s all-consuming desire for revenge instead of a vision of cosmic order, the play critiques the folly of blood vengeance and the price paid for it by the avenger. While achieving the short-term goal of retribution, Electra loses her moral compass and her very humanity, underscoring the tragic aspects of humankind’s violent tendencies and conveying a hard-earned lesson for both ancient mythical figures and modern mortals alike: allowing vengeance to dictate one’s actions results in a legacy of sorrow rather than redemption.

Published in Classical Wisdom