Had Julia Agrippina Minor (Agrippina the Younger, 15 CE-59 CE) known that her son Nero would ultimately have her killed, she might have reconsidered giving birth to him. Nero, ever persistent in his depravity, made three failed attempts to murder his mother before finally succeeding. Being of cowardly nature, Nero was too frightened to carry out the grim task himself; instead, he hired henchmen to do his dirty work. This brutal act not only underscores the extreme measures he took to secure power but also marks a significant turning point in his reign.

The turbulent connection between mother and son illustrates the complicated dynamics of devotion and treachery in the quest for imperial authority. Considering that Agrippina played a crucial role in placing her son on the throne, what could have caused their relationship to deteriorate? Moreover, how did Agrippina manage to evade certain death three times before ultimately facing her demise? What was the evolution of the tense relationship between Nero and Agrippina, from the moment Nero ascended to the throne to the tragic end of Agrippina’s life?

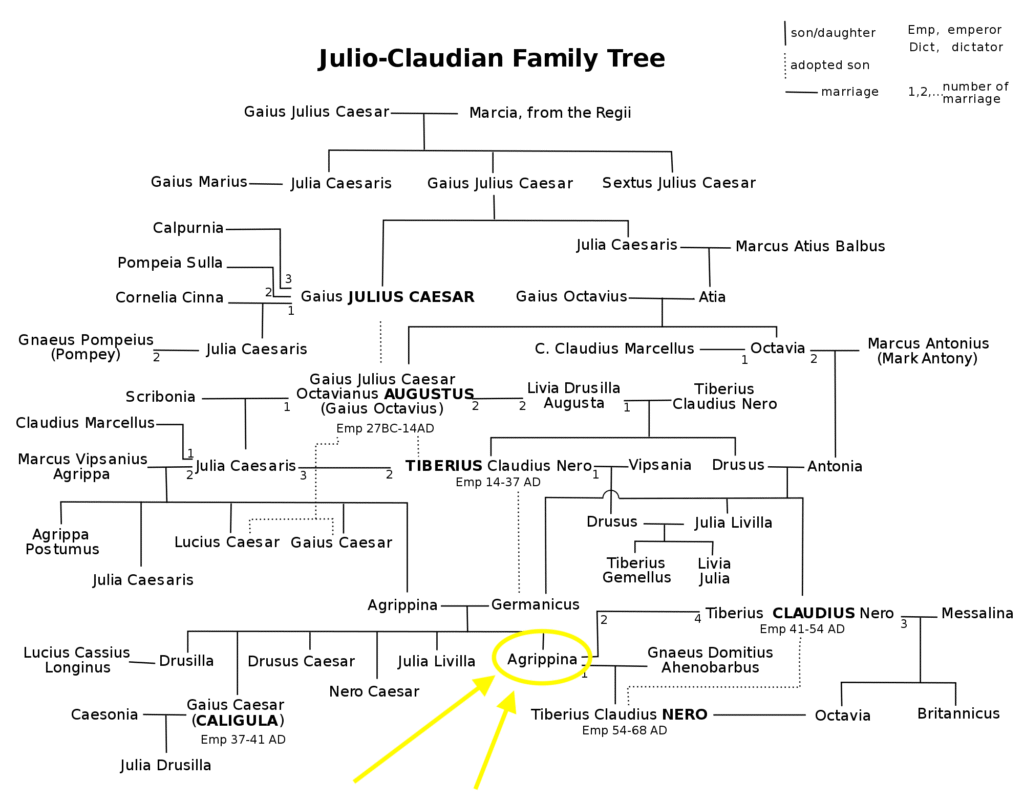

Agrippina the Younger was a Roman empress and the fourth wife (and niece) of Emperor Claudius. Cast in royal purple, she was the sister of Caligula, the third emperor, and the great-niece of Tiberius, the second emperor. However, her most significant direct relation was her great-grandfather, the first emperor, the “Divine Augustus,” who established the Julio-Claudian dynasty that her son, Emperor Nero, would ultimately bring to an ignominious end.

Ancient chroniclers, who rarely wrote favorably about powerful women, portrayed Agrippina as ruthless, ambitious, and domineering, which suggests that her greatest transgression may have been her forcefulness as a woman. Yet, with the blood of the divine Augustus coursing through her veins, who could blame her for being imperious?

On the night of Claudius’s death, Agrippina was busy setting the scene to prepare Nero for the role of a lifetime. Crowds gathered outside the palace, eager for news about Claudius’s health. The Praetorian Guard assembled to welcome and protect their new emperor. Within hours of Claudius’s death, the palace gates opened, and out stepped the fresh-faced, 16-year-old Nero.

By his side was Sextus Afranius Burrus, the Praetorian Prefect, who was both a former tutor and now an advisor to the new emperor. At Burrus’s nod, the Praetorians hailed Nero as “Imperator!” Soon after, the Senate proclaimed Nero emperor and granted him the necessary powers. No one protested—Agrippina achieved the seamless succession for which she had worked so diligently. Within a few short hours, she transitioned from being the wife of an emperor to the mother of one.

A note regarding Claudius’s death: Tacitus recounts how Agrippina worked with the infamous Roman poisoner, Locusta—who plays a prominent role in Julio-Claudian psychodramas—to deliver poison hidden in “particularly succulent mushrooms.” However, the poison was ineffective, and Claudius vomited instead. It is well-documented that he had a tendency to overindulge and often retreated to his bed to induce vomiting. The long-standing accusation that Agrippina poisoned Claudius relies on flimsy evidence, making it impossible to prove but effective in further impugning her reputation.

Questions remain, however. Following the emperor’s passing, his will was to be publicly disclosed but it never was. Unless Agrippina had ulterior motives, why would she choose to withhold the will, the ancients inquired? If the will designated his natural son, Britannicus, as successor, it would create an additional claim to the throne that Agrippina would vehemently oppose.

With her 16-year-old dependent in power, Agrippina was effectively in charge and determined to have Claudius deified––much like Augustus had been. A five-day-long funeral helped facilitate this, elevating her status significantly. She was now the widow of a god and chief priestess in his cult where she had—at long last—an official public role. Underscoring their parity, the first coins issued under Nero were of mother and son facing each other. Moreover, when they appeared in public together—which was often—he would walk beside the litter in which she was carried, making it look for all the world to see that it was she, not he, who was regent.

Because she was a woman, she could not openly appear on the Senate floor or in the Senate chamber but she was allowed to listen to Senate proceedings while concealed behind a curtain. Due to her unparalleled influence as empress, this arrangement was unprecedented and highly unusual.

Tacitus lamented the situation for Young Nero, saying: “What hope is there in a child led by a woman?” However, historians say that Nero couldn’t give a fig about governing—which sadly never changed much in his lifetime. He was a musician, an actor, and a poet, never a politician. Unlike his mother, he had no interest in public policy. So initially he let her run the show and everything was fine—until he fell in love.

By this time, Nero had been unhappily married to Claudius’s daughter, Claudia Octavia for at least a few years. Although politically well-matched, they were ill-suited in every other way. It was no secret that they loathed each other. So when his heart was captured by Acte—a Greek ex-slave on the palace staff—Seneca, the Stoic philosopher and statesman—now co-advisor (along with Burrus) to Nero, helped him hide the relationship from his mother.

All-knowing and all-seeing Agrippina found out about the affair before long and predictably went into a fury. “A handmaid for a daughter-in-law!” she cried, demanding that Nero return to his matrimonial bed where—it was hoped—they would produce the all-important Julio-Claudian heir.

For perhaps the first time ever, Nero defied his mother. He was the emperor, after all. Not only did he openly flaunt his affair with Acte, but he began to grow closer to his advisors, who were often at loggerheads with Agrippina. Thus began a clash of wills between his advisors and his mother, with the teenage Nero calling the shots. If she were angry about the affair with Acte, however, she must have been livid by what followed.

Nero dismissed one of Agrippina’s most stalwart confidants, Pallas, from court. Her right-hand man, Pallas had been a key financial advisor throughout Claudius’ reign. His name comes up time and again as more a friend and a confidant than a mere advisor for Agrippina. Nero, however, wanted to clean house and choose his own people. Upon discovering Pallas’s dismissal, an infuriated Agrippina cried: “I gave you the empire!”

She even threatened to pull her support of Nero and champion Brittanicus.

To be caught in a tug-of-war between Agrippina and Nero—a more dreadful destiny cannot be imagined. But nothing could have equipped her for what happened next. Over dinner one night, Britannicus fell ill and died—right there at the table. Agrippina became pale with terror. Never bosom buddies, Britannicus grew up with her son. Could Nero really poison his stepbrother with such disregard? Little did she know that this was just the beginning. Nero would later claim that Britannicus suffered from epilepsy and died from a seizure. Some historians today believe that it was epilepsy, not poisoning, that killed Brittanicus. Like much that comes to us from the ancient world, there is no way of knowing definitively.

Once again, however, the timing of his death was flawless. Britannicus was just about to receive his toga virilis—the ceremony that would usher in his manhood—and Agrippina was making overtures in his direction. He was just coming into his own. The famed Locusta’s name gets bandied about again regarding his death. Characteristic of something to hide, Nero had Britannicus’ body cremated posthaste, and predictably, his funeral was without pomp or ceremony.

Nero, however, was not finished asserting his authority. In another move against his mother, Agrippina was banished from the palace and relocated to a family estate, and her lictors, the German guard, and all the symbols of her regency were stripped away. For a woman who had spent most of her adult life in the public eye and had ruled the empire amidst great fanfare, Agrippina was now reduced to the secluded existence of a private citizen.

Despite the banishment, things appear to have stabilized between mother and son, until another love interest entered the scene.

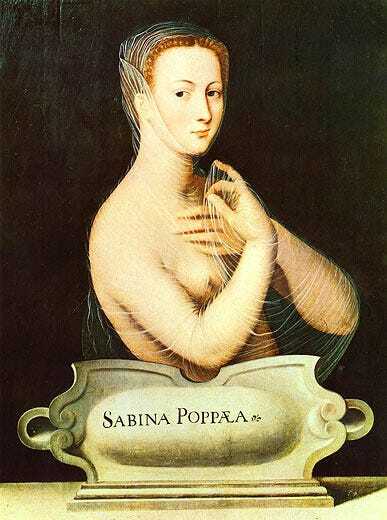

Poppaea Sabina was a married woman eight years Nero’s senior when she first took up with the young emperor. An incensed Agrippina opposed the union, still holding onto unrealistic expectations for a reconciliation between Nero and Claudia Octavia. But that was never destined to be. Sources suggest that Agrippina became so desperate for Nero to abandon Poppaea that she attempted to seduce him herself. According to ancient accounts, she was successful in her efforts. Numerous stories—some quite graphic—depict the couple being caught in flagrante delicto. As with most narratives surrounding incest within the royal family, it is prudent to consider them with a healthy dose of skepticism.

Nero divorced Claudia Octavia around this time on the grounds that she was barren. But divorcing her was not enough. According to Tacitus, she was beloved by the people, and so like many Julio-Claudian women who preceded her—he had her exiled then mercilessly killed.

After marrying Poppaea Sabina he resolved to kill his mother. What prompted the decision? It remains a mystery, though Poppaea—another strong-willed hence evil woman—is blamed for putting the odious idea into Nero’s head. It may be more complicated than that.

Even in her relative isolation, Agrippina continued to receive unwavering support from the fiercely loyal Praetorian Guard, who remained ever-faithful to the daughter of the late, great General Germanicus and could initiate an armed insurrection against her son on her behalf. The reality is that Nero was forever fearful of his mother, which is why his attempts to eliminate her come across as a dark comedy. Yet, Heracles-like, Agrippina managed to survive numerous attempts on her life.

Because he could not trust the Praetorian Guard, Nero had to make her death appear accidental. His first attempt— a method favored by the Julio-Claudian clan—was poisoning. However, this plan failed. The ancients agree that she not only had a well-stocked collection of remedies but also regularly took antidotes to ensure her immune system was fortified against any poisonous assaults.

Next, Suetonius recounts a poorly conceived scheme to have a ceiling collapse on her while she was asleep. He asserts that Nero himself envisioned a mechanism in her bedroom ceiling designed to release roof panels onto her head while she slept. The idea failed when her workers identified an issue in the design and swiftly rectified it.

Lastly, a collapsible boat stands out as one of the most sensational schemes from Nero’s reign. The plan was for the boat to “accidentally” break down while transporting his mother, who had been visiting his villa in Baiae, from her home, which was a few kilometers away. According to Tacitus, someone alerted Agrippina to the plot early on, prompting her to travel by land instead of by boat. Upon arrival, she was warmly welcomed by Nero and spent an enjoyable evening with him. Tacitus assures us that Nero was on his best behavior, which led Agrippina to let her guard down and allow herself to be escorted onto the ill-fated boat for transport back to her villa.

However, not all members of the crew were aware of the boat’s imminent collapse. After a canopy was dropped onto the boat, a clash of wills ensued: those in on the scheme attempted to capsize the boat while those unaware of the plot tried to stabilize it. In the ensuing chaos, both Agrippina and her friend and servant, Acerronia Polla, were thrown into the frigid waters. In a desperate attempt to save herself, Polla cried out that she was the emperor’s mother. Her plea, however, had the opposite effect; the assassins brutally bludgeoned her to death.

Agrippina, meanwhile, kept her wits about her and managed to swim to safety, cheating death once again. Numerous people died in the turmoil, but Agrippina was not one of them.

Imagine Nero’s shock upon discovering that his mother was still alive. He must have envisioned her storming into Rome, flanked by her loyal Praetorian Guard. Nero was in a frenzy. Thanks to the collapsible boat, his mother now knew he was attempting to kill her, which filled him with dread. After consulting with his trusted advisors Seneca and Burrus, he hired henchmen to go to her house and complete the task. When she realized the men were there to kill her, she is said to have shouted, “Strike here!” while pointing to her womb, which had borne the monster her son had become.

Ever the coward, Nero turned the tables and accused her of trying to kill him, even after he had accomplished the deed. He wrote to the Senate that his mother had hired a freedman to try to kill him but when that failed, she killed herself. No one truly believed him but the Praetorian Guard let him live. She was cremated the day she died and was accorded no public funeral. In their obsequity, the servile Senate thanked the gods for keeping their matricidal emperor safe.

While they were groveling thusly, there was a partial eclipse of the sun which was always ill-portent. In fact, his mother’s death marked the turning point in Nero’s reign. When she was alive, either running the government or advising him, Rome was a strong, stable, and prosperous state. But after her passing, ruled by fear and paranoia, Nero’s reign became increasingly erratic and Rome declined into chaos. In 68 CE, after fourteen years and much bloodshed, Nero was declared enemy of the state and ignominiously fled Rome in disguise. Too cowardly to kill himself, he hired a freedman to do the job.

So in the end, why did Nero kill his mother? Was she the monster he (and the Roman chroniclers) made her out to be? The truth is something we will never really know about Agrippina. What we do know is that the men who wrote about her could not be unbiased toward strong women; a fact which challenges every accusation against her. One thing is certain, in a world where women were irrelevant, Agrippina was in charge and the empire ran more smoothly on account of it.

Agrippina the Younger Selected Reading

Barrett, Antony A. Agrippina: Sex, Power and Politics. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

De La Bedoyere. Domina: The Women Who Made Imperial Rome. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018.

Dio, Cassius. Roman History: The Reign of Augustus. New York: Penguin Classics: 1987.

Flower, Harriet I. The Art of Forgetting: Disgrace & Oblivion in Roman Political Culture, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Freisenbruch, Anneliese. Caesar’s Wives: Sex, Power, and Politics in the Roman Empire. London: Free Press, 2010.

Holland, Tom. Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar. New York: Anchor Books, 2015.

Richlin, Amy. Arguments with Silence: Writing the History of Roman Women. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2017.

Suetonius. The Lives of the Twelve Caesars. Translated by H. M. Bird. London: Wordsworth Classics, 1997.

Southon, Emma. Agrippina: Empress, Exile, Hustler, Whore. London: Unbound, 2018.

Tacitus. The Annals. Translated by: J. C. Yardley. Oxford: University Press, 2008.

Wood, Susan E. Imperial Women: A Study in Public Images, 40 BC-AD 68. Leiden, NV: Brill, 1998.