The earth turned on its axis the day Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) died. Notorious for his unrestrained aggressivity and hard drinking, it should have come as no surprise to the Greeks that Alexander the Great would not live to see old age. Yet when the warrior king died at the age of thirty-two, it left a power vacuum the likes of which the ancient world had never seen, resulting in widespread unrest and turmoil throughout Alexander’s vast empire. His son, Alexander IV, by Roxane, his first wife, was born posthumously; thus, at the time of Alexander’s death, his gender was unknown, and Alexander’s half brother—Arrihidaeus—was cognitively impaired, therefore permanently considered a minor and his next closest male heir.

Due to the absence of a designated heir and the widely held belief that the Great Conqueror’s dying wish was to leave the empire “to the strongest,” chaos enveloped both the Macedonian court and his troops in Babylon. It was inevitable that his generals, who were formally Alexander’s “Successors,” would quarrel with one another over which of them should lead. This series of conflicts to control portions of Alexander’s empire was an era known as the War of the Diadochi (Successors) and lasted from 323 BCE-281 BCE. Eventually, the Successors grudgingly backed Alexander’s son (if he were to have one), but the Macedonian soldiers wanted Arrhidaeus to be king and threatened mutiny if the Successors disagreed. Before the empire was carved into what would become several major kingdoms, the notorious “Compromise of Babylon” was proposed where two kings—neither of them a fully functional adult—reigned.

As a consequence of this implausible arrangement, two women—Olympias (375-316 BCE) and Adea Eurydice (337-317 BCE)—each representing separate branches of the hallowed Argead dynasty—engaged in an improbable battle for sovereignty. Because succession passed throughthe male line, in Macedonia women wielded power only through proxy. While women might influence choices and hold important offices, their authority was reliant on their male relatives. Due to the lack of male heirs, Argead women often played key roles behind the scenes, forming strategic alliances through marriage and kinship to ensure their voices were heard and their interests protected in a realm that sought to marginalize them. By harnessing their intelligence and political savvy, Olympias and Adea Eurydice sought to secure their lineage’s claim to the throne and maneuver within the constraints of a male-dominated society where they were unable to take on direct leadership roles, such as military command. In what Greek historian Duris calls “the first war between women,” this article delves into the unlikely circumstances surrounding a battle in which two female leaders commanded opposing armies in a struggle for sovereignty. Some history about these two women is required before exploring the powerplay behind this clash.

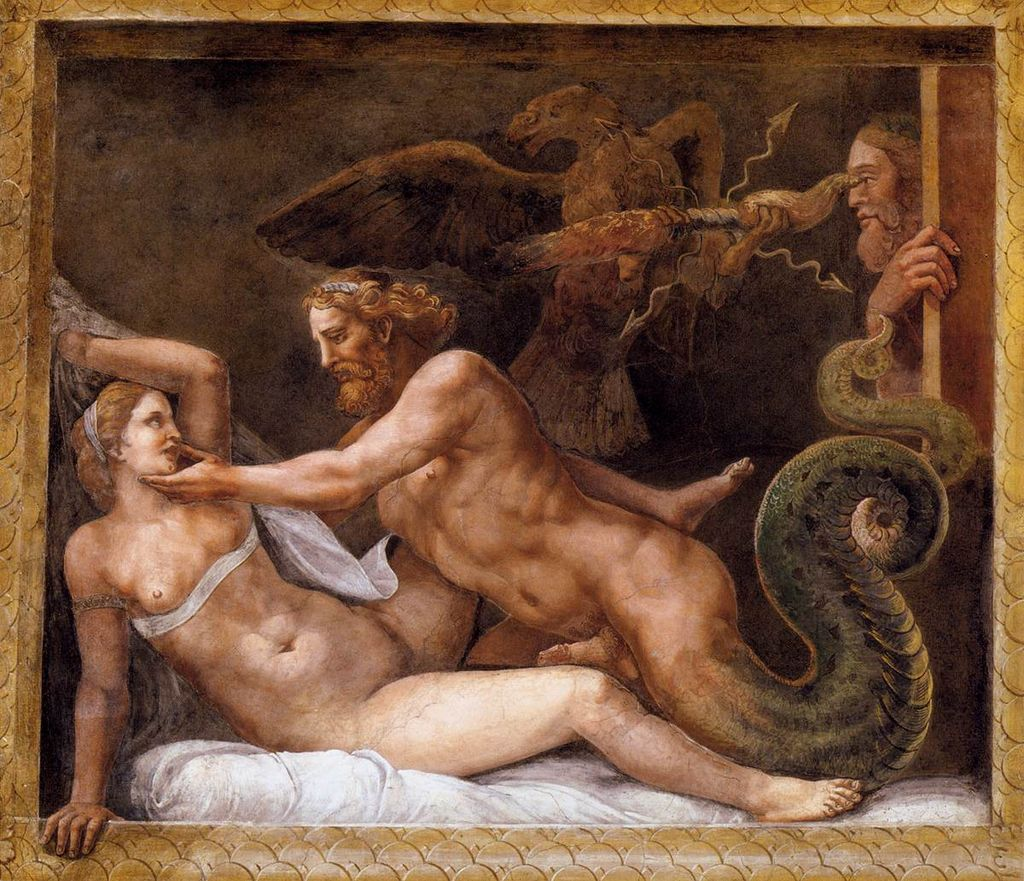

Wife of Philip II and overzealous mother to Alexander the Great, Olympias, was a descendant of the Aeacid dynasty of Epirus (in today’s northwestern Greece and southern Albania). Not only was she a fanatical follower of a snake-worshiping Dionysian sect, but she also maintained that Alexander was divine—the result of a coupling between herself and Zeus, the lord of the gods. Fraught from the start, Olympias’ relationship with Philip was indifferent at best; she was separated from him at the time of his assassination and was widely suspected of being a driving force behind it. Despite being one of Philip’s seven wives, Olympias was one of only three to bear a male heir, the youngest of whom she killed with her bare hands, according to the ancients.

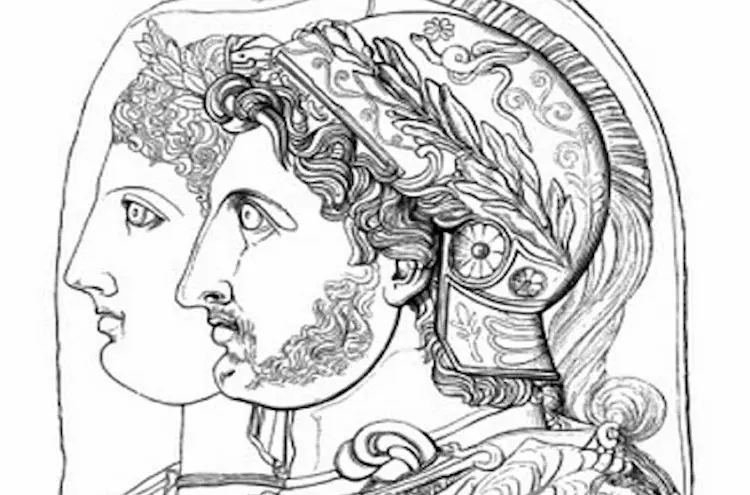

Although Olympias was more influential and well-known, Adea Eurydice’s claim outranks not just Olympias’ but also Alexander’s. Adea, whose maternal grandfather was Philip II, was a double Argead princess; Adea’s mother, Cynane, was Alexander’s half-sister and the daughter of Audata, Philip’s Illyrian wife, while Adea’s paternal grandfather was Perdiccas III, who was

Philip’s predecessor and elder brother. After Perdiccas III died, Philip usurped the throne from Adea’s father, Amyntas, who was a child at the time. In due course, Philip saw his nephew Amyntas as no threat and even arranged a marriage between Amyntas and his daughter Cynane—Adea’s parents. When Alexander assumed the throne, however, he felt otherwise and had Amyntas summarily executed. Adea’s final claim to the Argead throne was through her husband, Arrhidaeus, Alexander’s half brother.

Although they represented competing branches of the Argead dynasty, when Alexander was alive, these two women may not have seen each other as a threat. That changed, however, after his death, when the world flipped on its head. In 322 BCE, Adea entered the battle for sovereignty even while the Successors were vying with each other over who should lead. She and her mother, Cynane—with a more demonstrable claim to the throne than any of the Successors—raised an army specifically to set up the marriage between fifteen-year-old Adea and King (Philip) Arrhidaeus. Arrhidaeus’ name was changed to Philip Arrhidaeaus after he ascended the throne. After Alexander had killed her husband, Amyntas, Cynane’s animosity for the Alexandrian line of the Argead family ran deep. Upon his death, Cynane recognized an opportunity to assume her branch’s claim to the throne. As Philip II’s daughter and half sister of Alexander the Great, she successfully recruited an army that dodged troops in Macedonia and besieged the Macedonian regent on its way to a clash with the Macedonians in Asia.

Unlike her Macedonian counterparts, in addition to being an Argead, Cynane was a princess of Illyria, where it was culturally acceptable for women to acquire the arts of war; Cynane knew her way around the battlefield, and she provided excellent training to Adea. General Perdiccas (not to be confused with the king) was the first guardian of the two kings and saw Cynane’s confrontation as a danger to his control over the royal family. He dispatched his brother Alcetas to lead the royal army in resistance to the onslaught primarily because he and Cynane had once been childhood friends. Regardless of their previous relationship however, Cynane refused to obey Alcetas’ command to beat a retreat. According to second-century Macedonian author Polyaenus, “Alcetas advanced to give her battle. The Macedonians at first paused at the sight of Philip’s daughter, and the sister of Alexander…undaunted at the number of his forces, she bravely advanced to fight against him.” When they met on the battlefield, Cynane accused Alcetas of treachery and betrayal but in a startling display of savagery, Alcetas caught her off-guard and slayed his childhood friend while she was in mid-sentence.

The horrific killing of Philip’s daughter infuriated and shocked soldiers from both sides, who mutinied and demanded that Cynane’s wishes be carried out. Perdiccas reluctantly permitted Adea and Arrhidaeus’ marriage to calm unrest among the soldiers. After the marriage, Adea added Eurydice to her name to honor Eurydice I, the mother of Philip II and Adea’s paternal great-grandmother.

Within two years of this marriage, a proposed marriage to Cleopatra—Alexander’s full sister—brought Perdiccas’ regency to an abrupt end. Out of fear that Perdiccas would use his betrothal to Cleopatra to become heir apparent, the Successors waged the First War of the Diadochi (Successors), which ended in Perdiccas’ murder in 320 BCE.

After Perdiccas died, the two kings were placed under the custody of Antipater, a well-known commander whom Alexander had appointed regent in Macedonia prior to his Asia expedition in 334 BCE. Antipater had a long-standing hostile relationship with Olympias, whom he referred to as “a sharp-tongued shrew.” As a result of her significant influence in political matters, Olympias frequently wrote to her son to bemoan Antipater’s misuse of authority, to the point where Alexander started to support his mother in his final years. Consequently, Alexander recalled Antipater from his position as regent and summoned him to Babylon. Fearing that the summons would end in a death sentence, Antipater sent his son Cassander as an envoy to Babylon instead. Cassander and Alexander never had a close relationship, despite growing up together.

Plutarch claims that when Cassander saw Persians prostrate themselves in front of Alexander, he laughed. An enraged Alexander grabbed Cassander “fiercely by the hair with both hands [and] dashed his head against the wall.” Olympias publicly stated her conviction that Antipater and his son Cassander were complicit in a plot that resulted in Alexander’s untimely death.

When the 81-year-old Antipater died in 319 BCE, leaving the regency not to his son but to his trusted senior general, Polyperchon, Olympias must have been relieved. Her worries, however, were far from over. At half Polyperchon’s age, Cassander was still very much alive. Straight away, Cassander—feeling entitled to the regency that his father had handed to Polyperchon—planned a mutiny to depose Polyperchon, resulting in the Second War of the Diadochi, which lasted from 319–317 BCE.

Meanwhile, Polyperchon offered the guardianship of Alexander IV to Olympias. He asked her to return to Macedonia from her native Molossia in the Epirote state and also offered Olympias an authoritative function known as “basilike prostasia” inside his administration. But Olympias did not immediately accept the guardianship. She stood to lose a lot if she left the Epirote state. After her brother (and Cleopatra’s husband) died in 330 BCE, Olympias returned to her native Epirus to serve as regent to her cousin King Aeacides and had a number of high-profile duties. Eventually, she would accept the guardianship in order to defend her grandson’s claim to the throne and shield him from her adversary. Cassander, however, was not her only foe.

By this time, Adea Eurydice—a mere teenager—established herself as a queen with a voice that would not soon be silenced. In 321 BCE, at the partition of Triparadisus, where the Successors unofficially separated the empire between them, Adea Eurydice astounded everyone by delivering a passionate speech in favor of the monarchy. Her words so agitated the troops that they mutinied and sought to assassinate the newly appointed regent, Antipater, who narrowly escaped with his life. Adea Eurydice, as a double Argead whose dynasty the Macedonians revered, posed a serious threat not only to the effectiveness of the Successors but to their very survival. Ultimately safeguarded as regent, Antipater returned to Macedonia from Syria with Adea Eurydice, the two kings, and Roxane in tow. With a reputation as an authoritarian leader, Antipater kept Adea in check; for this reason, his death in 319 BCE was as liberating for her as it was for Olympias; as regent, Polyperchon, in contrast, was a pushover.

When Polyperchon departed for southern Greece in 319 BCE, he foolishly left behind the teenaged firebrand, who transformed herself from a powerless charge to a powerful adversary in his absence. Historians believe that she and Cassander must have reached an agreement when they both attended court at Pella around this time. Consequently, on behalf of her husband, the king, Adea wrote letters to the most influential Successors, asking them to recognize Cassander as legitimate regent instead of Polyperchon. As a result of her entreaties, the supreme commander in the East, Antigonus, accepted Cassander’s claim to regency and sent Cassander thousands of troops and a significant naval force. Adea Eurydice and Cassander formed an alliance, as both had goals that aligned against the Alexandrian line of the Argead dynasty. Adea Eurydice sought the protection of a Successor who commanded troops, while Cassander needed the legitimacy of the Argead bloodline to strengthen his claim to power. Their partnership served both their interests in challenging the existing power structure.

But the specifics of their relationship are unclear, according to 2nd century CE historian Justin: “Cassander, attached to her (Adea) such a favor, managed everything according to the will of that ambitious woman.” Cassander likely served as their commander, but it is unknown if Adea Eurydice or Cassander was Philip Arrhidaeus’s regent. Their relationship, however, may have been closer than mere political allies. According to epigraphic evidence, Cassander married Adea’s younger sister—also named Cynane like their mother—in 319 BCE. If true, in addition to being associates, Cassander and Adea Eurydice were family.

Yet for all her advantages, Adea Eurydice was in the undesirable position of serving as guardian to a sovereign who would never become a fully functional adult. Adea’s quest would have benefited from the production of a male heir; while they had been married for five years, there was no imminent pregnancy. The ability of Philip Arrhidaeus to father a child is uncertain. Because Alexander IV’s authority would eventually surpass that of Philip Arrhidaeus, Adea Eurydice’s position was considered secure as long as Olympias did not take custody of Alexander IV. While Adea Eurydice was primarily worried about overseeing a king whom Alexander IV would eventually surpass, Olympias was primarily concerned with Father Chronos himself.

Olympias finally accepted Polyperchon’s offer for two reasons: Cassander’s increasing success against his opponents and her need to protect her grandson. Polyperchon, proving to be an ineffective leader and a weak military commander, was losing ground to Cassander, who consistently outmaneuvered him in the ongoing conflict. Watching from the sidelines, Olympias was in a difficult position. Already in her mid-fifties, she could not expect her grandson to rule independently until around the age of 18, by which time, if she were still alive, she would be in her seventies. Because she could not count on living long enough to safeguard his autonomous rule, the best way to ensure his future was to eliminate the threats to his survival.

So in the autumn of 317 BCE the Pindus Mountains were the last obstacle in Olympias’ march from Epirus to Macedonia. However, she did not arrive to Macedonia alone. Olympias led an army with the help of her nephew, King Aeacides of Epirus. Duris tells us that Olympias, an enthusiastic Dionysian, entered combat cloaked as a Bacchante (Dionysian priestess). Did she pose as a Dionysian priestess in order to persuade the Macedonians, whose devotion to Dionysus was legendary? If so, she knew more about the Macedonians’ hearts and minds than her tender-aged opponent.

Adea Eurydice received word that Olympias was moving toward Macedonia while Cassander was on another front in the Peloponnese; in response, she sent a courier asking Cassander to assist her immediately. In the meantime, she took advantage of her Argead heritage to raise a large army and, with her gift of persuasion, approached the most powerful Macedonians with presents and pledges to come to her defense. Moreover, she recruited deserters from Polyperchon’s original troops. No older than twenty-one, this warrior queen assembled a substantial legion. However, Adea showed the impetuosity of youth by not waiting for Cassander and his reinforcements before she led her forces and her hapless husband, the king, onto the battlefield in Euria (in today’s southeastern Albania) to meet Olympias.

Olympias, majestically adorned in full bacchante attire, confronted Adea Eurydice, who brandished the armor of a warrior queen, underscoring their stark differences. The air must have been electric with anticipation as the armies faced off against each other. Seeing their former queen Olympias costumed as a prominent bacchante priestess may have been enough to prompt Adea’s Macedonian troops to defect one by one for her eminence. The rapid desertion of Adea’s soldiers demonstrates both the power of symbolism and Olympias’ alluring influence, which drew devotion from even her opponent’s ranks. In addition to admiring the brilliance of her late husband and son, the ancient chroniclers attribute the widespread desertion to a strong sense of awe for the bacchante priestess, their former queen.

After the bloodless battle demonstrated her political savvy, Olympias achieved her zenith of power and influence. Her hour, however, was short lived. According to some historians, she quickly lost the favor of the Macedonians due to the ruthless manner in which she killed the royal pair and many of Cassander’s allies. In violation of the law, she kept Philip Arrhideaus and Adea Eurydice locked inside a dungeon with little food or water. When the Macedonians began showing sympathy for the couple, she decided to have them executed instead. After dispatching Philip Arrhidaeus, Olympias presented Adea Eurydice with the choice of a sword, a noose, and a goblet of poison. The youthful queen chose to hang herself with her own garments, evoking Antigone, the eponymous heroine of Sophocles’ Antigone.

Although Olympias’ techniques for killing the royal couple were cruel, they were not unique for the period and location. As with most powerful women in antiquity, when a female leader displayed brutality, critics took her to task while ancients showered praise on her male counterparts for the same actions. Ultimately, her loyalty to vulnerable Successors—namely Polyperchon—led to her defeat. Within a year of her triumph over Adea Eurydice, Cassander led an invasion on Macedonia, seizing Olympia’s citadel in Pydna. When Pydna fell, Olympias surrendered to Cassander on the promise of her own safety. Cassander, however, had other plans for the queen. By denying her the opportunity to defend herself or face specific, formal charges, he set up a show trial and, amid the grievances of Olympia’s opponents, justified her execution: death by stoning perpetrated by the families of her victims. In a final display of disdain, Cassander denied Olympias proper burial rites. Then, in 310 BCE, to secure his own power in Macedonia, Cassander covertly ordered the death of Alexander IV, the boy king. He was fourteen years old at the time and, with his mother, Roxanne, was poisoned.

Doomed never to reach adulthood, King Alexander IV and his mentally handicapped Uncle Arrhidaeus were nothing more than pawns, allowing the Successors to declare their loyalty to the sanctified Argead dynasty while simultaneously furthering their own agendas. Although their physical presence was politically beneficial, the Successors never expected the two Kings to lead. The Compromise of Babylon, which incorporated two opposing claims to the throne, pitted the two most powerful Argead women against one another. But even while Olympias and Adea Eurydice battled each other, they were playing a rigged game; in the ancient world, men monopolized military might. Because the military was in the male domain, the Argead women needed the Successors’ protection; in contrast, the women were primarily a threat to the Successors. Illustrating the threat these women posed is the following grim account: in spite of the fact that they were not in the military, the Argead women frequently fought on the front lines. Throughout the Successor wars, rival factions murdered Cynane, Adea Eurydice, Olympias, her daughter Cleopatra, and Thessalonike (Alexander’s half-sister and Cassander’s wife) symbolizing the painful transition from the collapse of the Argead dynasty to the era of the Diadochi (Successors). The targeting of these women not only illustrates the turbulent power struggles of the time but also underlines the perilous position of powerful female figures in a male-dominated society.

_________________________________

Published in Ancient Origins

References:

Carney, E. 2006. Olympias: Mother of Alexander the Great. Routledge.

“ “ 1992. The Politics of Polygamy: Olympias, Alexander and the Murder of Philip. Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4426236.

Lyngsnes, O. 2018. The Women Who Would be Kings: A Study of the Argead Women in the Early Diadochoi Wars (323-316 BCE) in Academia.edu. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/38043400/_The_Women_Who_Would_Be_Kings_A_study_of_the_Argead_women_in_the_early_Diadochoi_Wars_323_316_BCE_The_Rivalry_of_Adea_Eurydike_and_Olympias

Miren, D. 2000. Transmitters and Representatives of Power: Royal Women in Ancient Macedonia. Peeters Publishers. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44079805.

Xhabrahimi, K. 2024 Adea Eurydice: The Teen Queen Who Shook an Empire. AlbanPedia. https://www.albanopedia.com/biographies/adea-eurydice#:~:text=Adea%20Eurydice%20was%20born%20sometime,Alexander%20III%20had%20Amyntas%20executed.