Evoking early agrarian rituals which celebrated the primal mysteries of birth, death, and resurrection, the Homeric Hymn to Demeter has the distinction of being amongst humankind’s first literary compositions honoring agricultural renewal and the great mother goddess tradition. Thought to have been composed within fifty or so years after Homer’s epics, the Homeric Hymn to Demeter was penned in the seventh century BC and is one of a series of 33 Homeric hymns which honor individual deities. They are called Homeric, not because they were composed— or sung— by the poet known as Homer, but because they employ the same meter used in the epics: dactylic hexameter or six feet per line. These Homeric Hymns were originally sung as prayers and while there is no record of a specific performance of the Homeric Hymn to Demeter—hereafter referred to as the Hymn— most scholars agree that a portion of the Hymn was likely sung at the cult festivals honoring Demeter. It is useful to note that up until the eighth century BC, Greek culture had been conveyed orally only—not by written documents.

The Hymn begins when an agreement is reached between Persephone’s father, Zeus— lord of the gods—and his brother Hades— lord of the underworld, to allow Hades to kidnap or marry Persephone without the knowledge or consent of either mother, Demeter, or daughter, Persephone. The kidnap is the event that spurs the action of the myth and resonated with women of the Greek world whose marriages were made in this fashion. At heart, the Hymn is a woman’s story. All the major roles are played by females and the areas of concern: marriage, agriculture, and sacrifice are in the feminine realm.

Matrilineal Succession

Moreover, the Hymn honors matrilineal succession—a detail often overlooked in Greek literature. The intergenerational relationships seen in the poem are between Demeter, Persephone, and Demeter’s mother, Rheia (Rhea). Rheia is the Titan mother goddess who is mother to six of those living on Mount Olympus and is, in turn, daughter to Gaia, Mother Earth herself, the paramount primogenitrix Earth Goddess responsible for both Greek pantheons—the Titans and the Olympians. In the Hymn, Demeter is twice referred to as Rheia’s daughter, moreover, Rheia, as grandmother to Persephone, ultimately, plays a pivotal role in the story. It is Rheia who mediates between Zeus and Demeter in finding a resolution to the crisis after Demeter stops the seasons when she holds the earth as ransom until Persephone is released from the land of the dead. Thanks to Rheia, Zeus finally intervenes by forcing Hades to return Persephone to her mother’s earthly domain. Hades adheres to Zeus’s request but not before luring Persephone into eating a pomegranate seed; the mere act of eating binds Persephone to Hades for a few months each year corresponding to the dormant winter season.

Time and again in Greek literature, students of the classical world take for granted the interplay between the male generations of the various paternal houses. Overwhelmingly androcentric, this is particularly true in the Homeric epics where women play a minor role to their leading men. When maternal genealogy comes up in these epics it is devalued next to the paternal bloodlines. But in the Hymn, beginning with Gaia and ending with Persephone, the family tree is matrilineal and noteworthy in its omission of males.

Zeus as father is in the story, but his presence is worthy of defiance. In addition to putting Persephone in peril at the outset, Zeus was unwilling to lift a finger to come to her aid. Ultimately, Zeus’s sovereignty was largely thwarted by the females, his superfluous intervention symbolizes patriarchal power which exists not only to separate women from each other but, perhaps more importantly, functions to suppress the conveyance of maternal genealogy.

In a society that separates daughters from mothers through virilocal marriage (where the bride resides with the husband’s family), not only was Persephone robbed of a loving mother, but she was robbed of a wizened grandmother and the thousand-and-one foundational stories about her foremothers that a matrilineal-rich culture would provide. By setting off the basic conflict, patriarchy supplants the mother-daughter dyad in favor of matrimony. To be sure, maternal lineage was inhibited when the young girls were spirited away from their natal homes, often never seeing their mothers again. Foley maintains: For ancient women, Demeter and Persephone may have represented the extraordinary endurance of the bond between women of different generations in the same family, a bond that carried women through the physical separation from their family that could so radically mark their lives.

Ultimately, matrilineal succession is restored in the Hymn when the bond between mother and daughter is seen as more powerful than that of husband and wife. Yoked to marriages over which they had no control, the Hymn was liberating for ancient women because the mother-daughter pair triumphed by subverting matrimony—the dominant patriarchal paradigm.

While the Hymn was crucial to apprehending meaning for adherents, the Thesmophoria’s ritual was necessary for its religious observance.

The Ritual Behind the Narrative

The relationship between mythology and religion is, to say the least, complicated. When does mythology become religion? Or do religions create myths? Religion can be all-encompassing; in addition to containing mythology, it includes other facets such as rites, theology, and mysticism. On the other hand, not all myths are associated with religions. All of this has to be taken into consideration when trying to understand the religion and mythology of ancient Greece.

Robert Graves argues that we may often consider other people’s religion to be mythology. This convention may be most strongly evident in the area of ancient Greek religion. Although most consider the traditional foundations of Western civilization to be avidly traced back to ancient Greece, the religious practices and beliefs of the ancient classical world differ significantly from the monotheistic belief systems represented by the Judeo-Christian traditions. “Perhaps because there is no written dogma in Greek mythology, nor commandments admonishing adherents on how to behave, ancient Greek religion may often appear to be composed of “doing” (rituals, sacrifices, festivals) as opposed to “believing” (adhering to commandments and other dogma).” Consequently, it might often be supposed from a Judeo-Christian perspective that the Greeks were less pious or committed to their religion.

But in a culture that credits its very sustenance on the capricious whims of the gods, piety takes on a new meaning. This is because religion was an around-the-clock endeavor for ancient worshippers whose lives could turn chaotic on a dime; not only did they pray to their deities for support, but they were obliged to offer up sacrifices to honor and appease them as well. So vital was religion in their everyday lives that its practice was viewed as essential for the smooth operation of democratic rule.

In her paper titled, “Feasts, Citizens, and Cultic Democracy in Classical Athens,” discussing the polis of Athens in particular, classicist Nancy Evans makes a persuasive argument for what she calls “cultic democracy: “Spheres of influence that we view as distinctly separate, namely political activities among humans and cultic activities aimed at the gods, overlapped in the lives and behaviors of the Athenians, and Athenian democracy could only function well when political and cultic activities were properly combined.

Given that religious expression was part and parcel of their daily lives, the role religious festivals played within the operation of the polis cannot be overstated.

The Thesmophoria: The Ritual of Fertility Festival

In the most highly anticipated religious festival of the year, women came from far and wide to gather in their cities to celebrate the Thesmophoria. Primarily a fertility cult, the Thesmophoria ushered in the sowing season and was one of a series of fertility cults devoted to human as well as crop fertility. In Athens, it was celebrated in the month of Pyanopsion (October-November) on the 11th through the 13th in the area known as the Pnyx—a prominent hill where the general assembly of the polis met.

Membership in the Thesmophoria was restricted to citizen-wives, in other words, wives of male citizens. Make no mistake, there were no female citizens in ancient Greece. Greek women, daughters of male citizens who then married male citizens were called citizen-wives because they reproduced the ever-coveted male citizens. Further, no maidens nor female slaves were allowed to participate in the Thesmophoria. And finally, men were strictly prohibited from enjoying, participating, or witnessing any portion of the ultra- secret feminine festival.

The first day of the Thesmophoria was called anodos, “way up” or “ascent” and refers to the torch-lit procession which leads up to the Thesmophorion, on the north slope of the Pnyx, beginning the festival. While Demeter’s sanctuaries were often on hills, there is a double meaning to the term “ascent”. It also refers to Persephone ascending from the depths of Hades—the prime reason for the festival. By ascending the hill to Demeter’s sanctuary, the women were imitating Persephone’s climb from the underworld. Depending on the size of the polis, the sanctuary might have had to accommodate thousands of women who set up huts or shelters within its open space. In Athens, for instance, they were camped out for three days and nights. The primitive huts were a token of the great antiquity of the rites; returning to the primeval housing where ancient agricultural people once lived.

The momentous second day was the fast or nesteia and recalled Demeter’s grief at the loss of her daughter. Nesteia was a day of deep mourning when adherents sat on their mats refusing food and wine as an act of mimesis for Demeter’s fast in the Hymn. Seldom given license in much else within the public sphere, female mourning in groups was a common practice in ancient Greece where women were encouraged to lead in public grief as “performers of the lament.” Moreover, it was not uncommon for the mothers at the festival to have collectively either lost a child to death or a daughter to marriage, ergo they could identify with Demeter’s grief at the loss of her beloved daughter.

On this earth-shattering second day of the Thesmophoria, most scholars believe that the women participated in “shameful talk” or aischrologia. Bawdy talk correlates with the jesting done by the maid servant, Iambe, which lightened up Demeter’s dark spirits in the Hymn. In fact, profanity was celebrated in the Thesmophoria and other Demetrian festivals associated with the powers of reproduction such as menses, lactating and childbearing; processes which were frowned upon in the male-dominant culture. Classics Professor Emerita, Eva Stehle submits: “In the Thesmophoria…these are sources of power; pollution correlates with women’s sexual autonomy for aischrologia or foul speech and bailing both excite Demeter’s reproductive vitality.” Countering appropriate feminine behavior, the shameful talk was a subversive act that was empowering for the citizen-wives who were expected to be shy and modest within their male-dominant culture. Further, shameful talk had a sexual component to it which may also have included the handling of artificial likenesses of genitalia, an ancient source suggests.

Once again, demonstrating control of their bodies, the bawdy talk was believed to encourage fertility and was often associated with Demetrian festivals, especially those where women were gathered in secret rites or mysteries.

Like adherents of any faith, the Greeks practiced their religious devotion through ritual. While a student of ancient history might not fully relate to the ritual practices of the ancients, to the ancient worshiper, the transcendent rituals observed at festivals brought the myths to life by emanating the eternal. By evoking the primordial era, the cult practice of the Thesmophoria accessed some of its appeal from its very genesis. The citizen-wives of the Thesmophoria found empowerment in the mimesis of the prehistoric rites since prehistoric women were more autonomous than their Greek counterparts, leading renowned classicist Froma Zeitlin to espouse: “The building of temporary huts, the use of acts of woven osier for sleeping on the ground, the curing of meat in the sun instead of roasting it with fire and the inclusion of foods which predate those of the grain culture…all point to a primitive state of development consonant with the myth of time when women were in charge.”

Implicit in the primordial rituals is women’s authority in the Thesmophoria. For ancient Greek women, the Thesmophoria bestowed a link to an era before patriarchy became the law of the land and women’s role was supreme. As with all religions, transcendence with the eternal tends to get passed down from one generation to the next. This is believed to be especially true for the adherents of the Thesmophoria who rigorously kept their faith through the ages.

Which Came First Myth or Ritual?

One element of the ever-secretive Thesmophoria’s appeal is that its very genesis harkens back to the primordial fog of prehistory. After all, Demeter herself was believed to have formed the woman’s-only religion. However, the Hymn was composed in the relatively recent Archaic era (800-480 BC), therefore is it possible that the cult practice of the Thesmophoria preceded it?

Which came first, myth or ritual? The aetiological order of myth and ritual is a debate that has been raging since Harrison, argued in favor of the ritual preceding the myth: “The myth of the rape of Persephone of course really arose from the ritual, not the ritual from the myth.” Contending that the Thesmophoria was of “immemorial antiquity,” Harrison’s claim was that all mythology represents a means for explaining irrational rites passed down through the ages. In other words, myths were created after the rituals were in practice, giving adherents an understanding and acceptance of practices that may have dated back to primeval times. In light of this, the rites of the Thesmophoria closely follow the events of the Hymn, indicating that the Hymn was written with the rites in mind.

Harrison was not alone in espousing that ritual practice preceded myth. More recently eminent Eleusinian mysteries scholar, Kevin Clinton, refers to the Hymn as an aition (a story used to explain the origins of a ritual) of the Thesmophoria, contending the rites were in practice before the myth was composed. Because the practice of the Thesmophoria dates to the Neolithic era—-as most scholars now agree—female disciples throughout the Greek world practiced their religion long before the narrative known as the Hymn was composed. Regardless of the lack of a cohesive narrative for the early disciples, archaeological evidence suggests that the women of the Thesmophoria were considered religious both in the spirit of the festival and its sacred rituals. Practiced by orthodox women who “kept the Thesmophoria as they always used to do,” over hundreds, perhaps thousands of years, the rites of the festival were renowned for their constancy.

Extracts from the Cult of the Captured Bride, (2023) by Mary Naples

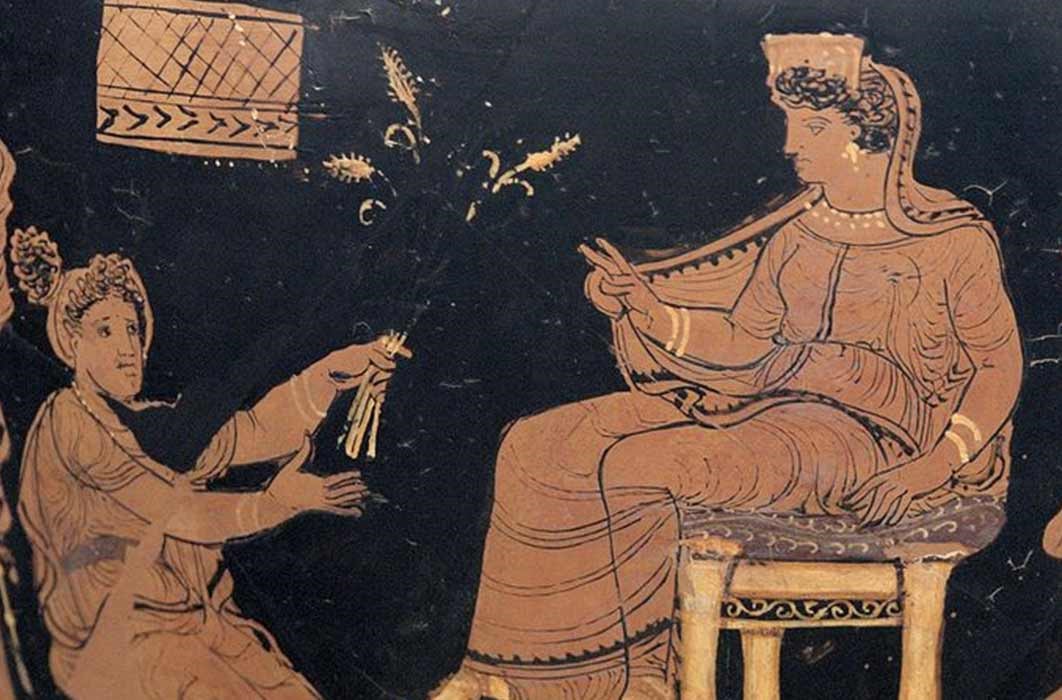

Top Image: A dedication to Bacchus by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1889)(Notice the pomegranates on the table on the right) (Public Domain)

By: Mary Naples

References

Clinton, K. 1993. The Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore at Eleusis. In Greek Sanctuaries: New Approaches, ed. Nanno Marinatos and Robin Hagg. London: Routledge

Evans, N. 2004. Feasts, Citizens, and Cultic Democracy in Classical Athens. Ancient Society 34

Foley, H. P. 1994. (ed) The Homeric Hymn to Demeter. Princeton University Press: New Jersey

Graves, R. 1968. Introduction in New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology. tr. Richard Aldington and Delano Ames. London: Hamyln

Harrison, J.E. 1991. Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion. New York: Princeton University

Press

Stehle, E. 2007. Thesmophoria and Eleusinian Mysteries: The Fascination of Women’s Secret Ritual. In Finding Persephone: Women’s Ritual in the Ancient Mediterranean, ed. Maryline Parc and Angeliki Tzanertou. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press

Zeitlin, F.I. 1996. Playing the Other. Chicago: University of Chicago

Published in Ancient Origins