When the executioners came for her on that otherwise bright and sunny day, Cornelia (50-91 CE) was many things, but penitent was not one of them. Never one to go gently into the night, Cornelia raised her hands in supplication to her patron deity, beckoning Vesta—goddess of the home and hearth—to come to her rescue and pleading for mercy from the other gods. But alas, as is customary when appealing to the gods, there was no reply. Claiming her innocence throughout, Cornelia railed against Domitian (51-96 CE)—emperor at the time. Crying out “Caesar thinks I am impure, I who have performed many rites, by which he conquered and triumphed.” Living up to his reputation as tyrant, Domitian in his role as Pontifex Maximus (chief priest) convened a session of the sacred college in order to convict Chief Vestal Cornelia of the gravest crime and subsequent punishment of the Vestal order—incestum (unchastity) and live burial. Unlike most criminal proceedings against Vestals, this particular session was conducted without the accused there to defend herself, something so notable that Pliny the Younger (61-113 CE) made mention of it in his description of the entombment of Cornelia.

But who were the Vestal Virgins and why was their sacred oath of chastity so fundamental to the cult? Further, why was the merciless live burial the common method of execution for a fallen Vestal? Though today many believe that the cult of Vesta had Etruscan origins, according to Roman historian Livy (59 BCE-70 CE) the College of Vestals was founded by the legendary second king, Numa Pompilius (753-673 BCE) in the seventh century BCE lasting until 394 CE, when Theodosius I (347-395 CE) dissolved pagan religions by decree in favor of Christianity—forever quenching the sacred fire. Alas, the twilight of the Vestal Virgins mirrored the fall of the Roman Empire with only eighty-two years separating them in a history that spanned a millennium. As an aside, after the fall of the Roman Empire in 476 CE, many ancients argued that it was the brutal exodus of the pagan gods and the subsequent advent of Christianity that led to its downfall. Saint Augustine’s (354-430 CE) book Confessions was written as a rebuttal to that argument.

The cult of Vesta was so integral to the story of Rome that the mother of its twin founders, Romulus and Remus, was one of them. Vestal Rhea Silvia, like many legendary virgins of the day, was forcefully impregnated by a god—in her case, the god of war, Mars. Woefully, the first Vestal Virgin was also the first Vestal to be executed for breaking the sacred vow of celibacy. Meanwhile, the twins were left to die by exposure but instead were set afloat in a basket down the Tiber River where they were eventually reared by a she-wolf, or so the legend goes. Although the fate of Rhea Silvia was sadly mirrored by some of her unlucky successors, happily many more lived to see the end of their term.

Recruited between the tender ages of six to ten, there were only six Vestals at any given time. These girls were oftentimes selected from patrician families and served Vesta for a period of thirty years. Although Vestals were permitted to marry after serving their thirty-year term of service, they seldom did. The Vestals were the only exclusive female priests in the Roman Religion; in service to Vesta, one of its most paramount deities. Why was Vesta so all-important to the Romans? The truth is Vesta’s origins may have been as old as fire itself. Long before ancient Rome, early societies made protecting fire’s perennial source part of religious ritual; inasmuch as it was deemed magical in origin while being indispensable to everyday lives. As Vesta’s priestesses, the Vestal Virgins, were tasked with keeping Rome safe which meant making sure the sacred fire never burned out.

Because there was no accessible source of fire in early Rome, it was important for the health and well-being of the state to have an ample supply of it. The Romans believed that if the Vestal fire should die out, Rome’s very existence would be threatened. Further, because fire was not easy to kindle for the average Roman, the Vestals were instrumental in making it accessible to all Roman homes. In addition to making certain that the sacred hearth was always lit, the Vestal Virgins performed other rites and religious duties such as food preparation used in rituals, amassing water from the sacred spring and handling and tending to sacred objects.

Forasmuch as they bore the responsibility of keeping Rome safe, Vestals did not have the inhibiting restrictions imposed on them as on other Roman women. For example, they could own property and possess wealth; with some of the Vestals becoming quite rich during their tenure in the cult. Owing to property ownership, Vestals were also allowed to make wills. And perhaps most significantly, they could vote, just like every other Roman male citizen.

Living under their husbands’ patriarchal thumbs, is it any wonder that many Roman women were envious of their Vestal sisters? The public treated them munificently as they were considered the very essence of what it was to be Roman. As an illustration of the respect they received, Vestals were transported by carriage (carpentum) wherever they went and always had the right of way. Their person was venerated, and the penalty for injury to a vestal, through accident or otherwise, was death. Because of their holiness, in addition to having the authority to pardon condemned prisoners, they performed rites before important battles in order to assure a Roman victory and had the ear of the emperor; Augustus always included them in all major dedications and ceremonies. Being above suspicion also entitled them to be in charge of keeping the wills and testaments of luminaries such as Julius Caesar and Marc Antony. So vital was their authority that the Vestals came to the aid of a young Julius Caesar, gaining him a pardon after Sulla put Caesar on his death list. In light of all these rights and more, life wasn’t so bad for a Vestal, that is unless a she broke her burdensome vow of chastity.

For above all, a Vestal had to be a virgin, their virginity was considered critical to the health of the state. At an early age, the Vestals left the authority of their father’s home to be inducted into the authority of the state. By virtue of this installation, the Vestal Virgins were considered to be daughters of Rome, therefore making any sexual relationship with a citizen both incestuous and a treasonable offense punishable by death. It is believed that if a Vestal broke her vows there would be a dangerous breach in protocol or pax deorum (peace of the gods), which assured the continuity and success of the Roman state. To be sure, the triumph of Rome depended on the purity of their ritual and its purity depended upon their chastity.

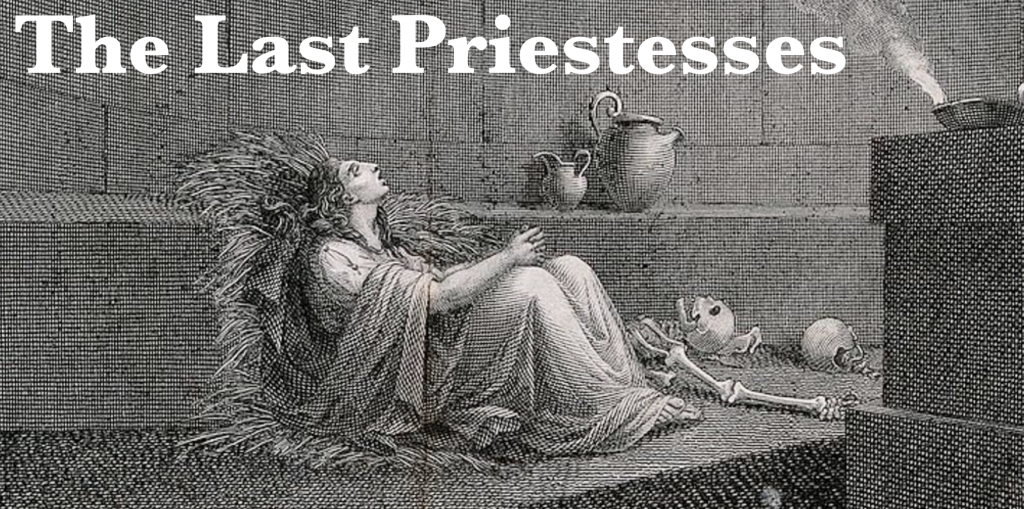

Although “punishable by death” was a vexing proposition for the Romans, as Vestal’s bodies were considered inviolable, how then should wayward Vestals be punished? The fifth king of Rome, Tarquinius Priscus (616-579 BCE) devised the punishment of live burial for reckless Vestals. But because Roman law prohibited burial within its city walls, Priscus formulated a method where the Vestal was buried alive in a chamber containing a bed, some blankets and a lighted lamp along with food provisions to last a few days. The thinking was that because Vesta was an underworld goddess, if she so deemed it, she could rescue her buried priestess. In point of fact, Romans went to a great deal of deliberation to institute live burial so that Vesta would not punish them for the bloodshed of one of her priestesses, so apprehensive were they of the wrath of one of their most supreme deities.

While Romans may have lived in fear of the wrath of Vesta, their dread didn’t preclude them from using her priestesses as scapegoats from time to time. Because live burials often coincided with times of political upheaval, some suggest that Vestals may have been used as fall guys for the state. After all, who better to blame for failures of state than the priestesses tasked with keeping Rome safe? Ultimately, the fate of the vestals rested with the Pontifex Maximus (chief priest and emperor—since Augustus 27 BCE-14 CE) and his sacred council of three pontiffs or priests. Could this patriarchal convocation have always been fair and unbiased to the priestesses? Alas, it is believed that while some of the executed Vestals may have broken their sacred vows, many more were used as political pawns.

Only two years away from completing her thirty-year term of service to Vesta, Chief Vestal Cornelia was paraded through the streets in a funereal-like procession on her way to live entombment. Eventually resigned to her fate, as she descended the steps of the ladder leading to her underground crypt, Pliny the Younger reports that she stumbled when her robe caught. Ever the priestess, she remained poised and collected throughout, unfastening the robe and steadying herself as she haughtily shunned the executioner’s offered hand of assistance. With the warmth of the sun at her back and a cool breeze on her face, she made her way down the steep steps into the pitch-black and airless underground chamber that would serve as her sarcophagus.

Published on Classical Wisdom

Mary, this is fascinating, what a wonderful project. I want to read them all!

Thank you