Who were Demeter and Persephone and why did their myth resonate so strongly with women of ancient Greece? The story of Demeter, goddess of the harvest, and her daughter Persephone, queen of the underworld, has inspired many. And while there are twenty-two variations of the myth, it is the Homeric Hymn to Demeter (hereafter called the Hymn), composed between 650-550 BCE, that is believed to be one of the oldest.

Undoubtedly, the episode that leads up to the narrative found in the Hymn to Demeter is as important as their story itself, as it sets the tone straight away. It starts with Zeus, lord of the gods, who rapes his sister Demeter, and the product of that rape is Persephone. They never married. Indeed, Zeus would have been the husband to hundreds if he married everyone he raped.

The famous Hymn then begins with the reciting of Zeus’ agreement with Hades in regards to Persephone. To be sure, his being an absentee father did not stop Zeus from arranging the marriage of his daughter – unbeknownst to either her or her mother – to his brother—Hades, the lord of the underworld.

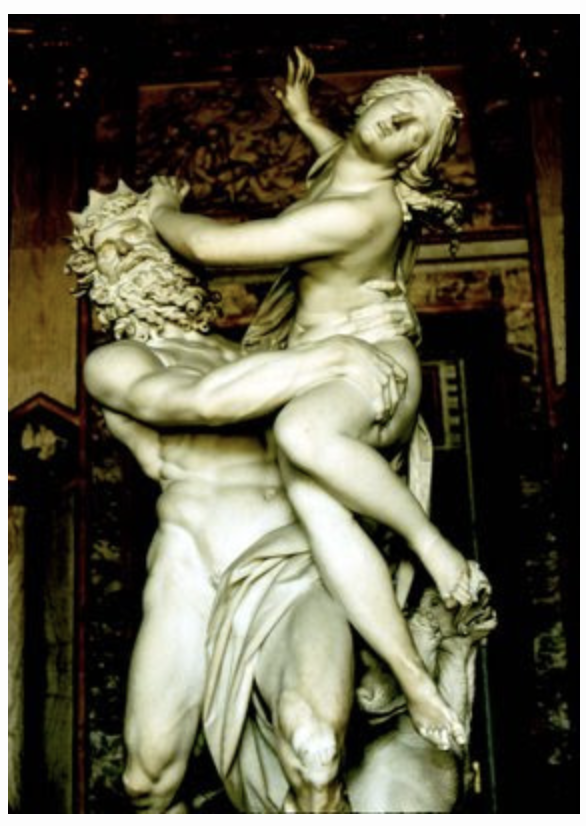

As a result, one day while Persephone was out picking flowers with her friends, the earth cleaved open and Hades, on a horse drawn chariot, charged out violently, snatching Persephone to be his wife for all eternity in the underworld. Persephone shrieks at the violence of the attack, alerting Demeter to her peril.

Inconsolable at the loss of her daughter, Demeter roams the earth in search of Persephone. No one, god nor mortal, has the courage to tell her what became of her daughter. Finally, through information gleaned by the pre-Olympian goddess Hecate, Demeter is informed of Persephone’s rape.

Upon discovering that Zeus made the perfidious bargain with Hades, Demeter withdraws from her residence on Mount Olympus, and instead makes her home in an agrarian community populated by mortals. After many trials and tribulations there, a grand temple is built in Demeter’s honor with attendant rites to conciliate her spirit. But these honors are not enough to appease the grieving goddess.

It is at this point in the story that Demeter realizes her full strength. As a means of regaining her daughter from Hades, she exploits her power of fertility and stops the seasons, turning the earth into a barren wasteland. Reluctant to see the planet he shepherds whither away, Zeus pleads with Demeter to make the earth abundant once again. But Demeter will not relent until Persephone is released.

Finally, Zeus intercedes on Demeter’s behalf and orders Hades to return Persephone to her mother’s earthly domain. Ever obedient to Zeus, Hades adheres to his instruction but not until he lures Persephone into consuming a pomegranate seed. The mere act of eating in the underworld binds Persephone to Hades as his wife for a few months out of every year.

So how did this parable of the kidnapped bride ring true for women living in ancient Greece? Living under their husbands’ patriarchal thumbs, women were accustomed to being kept out of the loop regarding the matrimony of their daughters, and as such, it was not unusual for a father to bargain with his future son-in-law about the fate of his daughter without the knowledge or consent of either his wife or daughter.

As a girl was often torn from her natal home and forced to marry an unknown man who was—on average—twice or three times her senior, abduction can be seen as the equivalent of rape. After all, men were taking young girls to be their wives, that is to say, the begetters of their sons. Indeed, some military campaigns were undertaken for the express purpose of rape; many Ionians and Pelasgians (early Greeks) were said to have gotten their wives in that manner.

Furthermore, in patriarchal ancient Greece, marriage was virilocal. In other words, the young girls—most of whom were sixteen years of age or younger—were forced to reside in their new husband’s family home, which could be a great distance from their original home. This meant having contact with their own family members after their marriage was a rare occurrence.

Consequently, Demeter’s sense of powerlessness against the abduction, and the suffering that ensued at the loss of her daughter, could resonate for most women of ancient Greece.

Additionally, although males are present in the account, it is a woman’s story. All the major roles are played by females, and the areas of concern: marriage, agriculture and sacrifice are indubitably in the feminine domain. To be sure, the dark bargain made by the male deities is a misbegotten one, as the union produces no child and nearly brings an end to the life of the planet. Indeed, although their actions drive the events, Zeus and Hades are remote shadows, whose dark force propels the dissonance felt by mother and daughter.

At its most fundamental level the Hymn is a story about a mother’s grief at the loss of her beloved daughter. Told from the perspective of the mother; it is more Demeter’s story than Persephone’s. At once powerless and inconsolable, Demeter appears more mortal than divine. Suffering profoundly due to the actions of males, Demeter is initially impotent to set things right. It is this sense of helplessness that sets off her sorrow at the loss of Persephone, mirroring the anguish that must have been felt by mortal mothers who lost their daughters to marriage each day.

Although both are parents to Persephone, Demeter’s bereavement is in marked contrast to that of Zeus, who had initiated her abduction in the first place. Bargaining with the lord of the underworld, who most would view as an agent of death; Zeus is indifferent to his daughter’s banishment into the land of the dead. In other words, he is disinterested in his daughter’s fate. Though immortal, Persephone is spirited away from the living cosmos and is compelled to live in the realm of the underworld for eternity.

Indeed, is Persephone’s marriage not a sort of death? Seen as a transition, the marriage of a maiden was viewed by many as a symbolic form of death.

But it is Demeter who does something never seen before in Greek mythology – she dares to defy the will of Zeus. Moreover, not only does she live to tell the tale but she very nearly wins the battle. After all, for the majority of the year Persephone lives with her mother in the light of her mother’s earthly domain. Though life can never return to the way it was before the abduction, most mortal women could envy Demeter’s achievement. In this way, the Hymn was liberating for ancient women, an example of a mother’s triumph over all else.

The original publishing can be found at Classical Wisdom

This is an amazing story! It shows how there’s no greater love than the love of a mother.

Thanks for sharing it!

Thanks for the comment. I’m glad you liked it.