It must have come as no surprise to the Greeks that the face, which launched a thousand ships, was of Spartan origin. After all, Spartan women were known throughout the Greek world for their seductive beauty and disarming promiscuity.

Is it any wonder that, in a polis that celebrated nudity and encouraged its citizen wives to engage in marital infidelity, its women should be thus renowned? Like all Spartan girls, Helen, would not have been shy or modest about her nudity. This cavalier attitude toward undress would have been scandalous throughout the rest of the Greek world where it was deemed appropriate for citizen wives to be conservative in dress, and in marked contrast to their Spartan sisters, wear multiple layers of clothing.

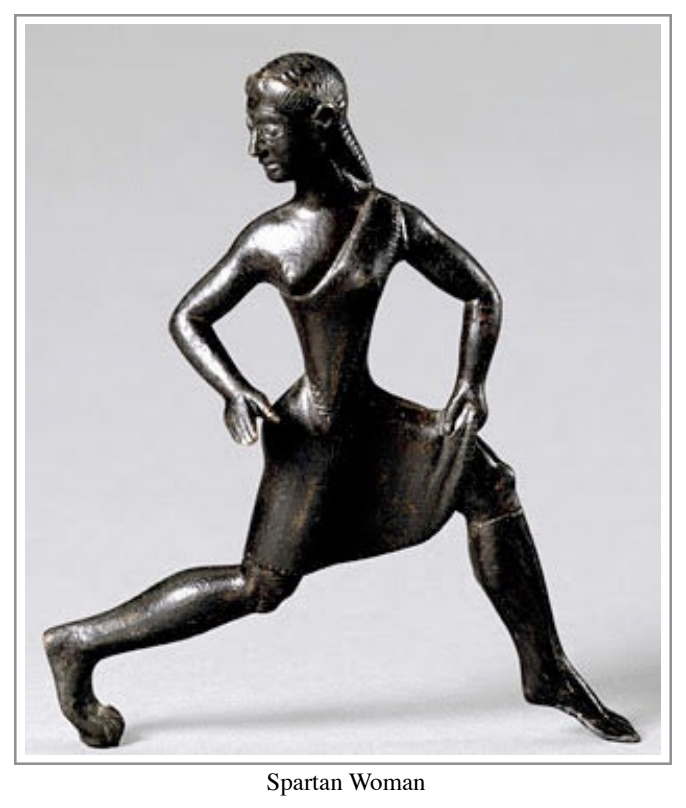

However, nudity or scant clothing was an important factor in athletic endeavors for both genders. Unlike other Greek poleis, physical training was integral to the health of Sparta; boys and girls trained together in the nude up until the age of seven at which time the boys were segregated into their intense military regiments. Although sent home, the girls’ physical training was far from over as their mothers continued their education in running, wrestling, discus and javelin throwing. What else could one expect from a polis that focused on physical training and martial might to the exclusion of nearly everything else? After an extreme and oftentimes-brutal military education, the goal of Spartan men was to become the best soldiers in the world thereby creating a military that was without compare. Likewise, for Spartan women, through a regimen of intense physical training, their goal was to reproduce the healthiest offspring in the world.

On account of this emphasis on health and fitness, Spartan girls married in their late teens in contrast to their Greek counterparts who married in prepubescence. The thinking was that women gave birth more easily and produced healthier progeny when they themselves were more mature. Unlike in other Greek poleis where the groom was typically 15 or so years older than his bride, Spartan wives were around the same age as their husbands. In many ways, the state of Sparta was before its time in such notions as pre-natal care. To be sure, women in the Greek world ate meagerly compared to their male counterparts often suffering from malnutrition and anemia. Not so in Sparta, they understood that healthy women produced healthy children and women’s food rations were on par with that of men. In fact, many scholars assert that on account of the privations of war, Spartan wives often ate better than their husbands.

Owing to the girls living at home much later, it is believed that in addition to physical training the girls were also educated in the liberal arts and learned reading, writing as well as music, dancing and poetry. Additionally, according to such primary sources as Plato and Plutarch, Spartan girls were trained in philosophical discussion and were encouraged to make their views heard publicly as well as privately. Conversely, in much of the Greek world it was deemed improper for a respectable woman to speak unless it was to or through her husband. It is interesting to note that liberal arts education for Spartan men was believed to have been….well… spartan. Many scholars assert that because of the hyper-focused and at times extreme education in martial arts, Spartan males had little time to learn much of anything else making their education in rhetoric and the liberal arts far weaker than their Greek counterparts.

Living in the barracks with other men even after getting married, homosexuality was not only prevalent, it was state endorsed. Again because of Sparta’s fierce militarism, the reasoning was that men would fight more bravely if they felt affection for each other. Conversely, newlyweds were encouraged to see each other infrequently. It was supposed that if a husband and wife saw each other sparingly, the urge to procreate would be more strongly felt on the rare occasions that they did see each other thereby producing more robust progeny. Until they reached the age of thirty, men could only visit their wives surreptitiously under cover of darkness on nights when the moon was not out. It was while their husbands were away from home that the wives became accustomed to being in charge of the oikos or household.

Most scholars contend that Spartan marriage customs allowed greater freedom to women than their Greek counterparts. In other Greek poleis, an adolescent girl was spirited away to her new husband’s domain living under the rule of her much older spouse, whereas a Spartan wife was largely in charge of her household and either continued living with her parents or stayed close by while her husband was away from home either in the barracks or on military campaigns.

In direct contrast to the rest of the Greek world, Spartan males had a more difficult life and thus died younger than their female counterparts. In an effort to weed out the weak, Sparta engaged in male infanticide. Through a process akin to eugenics, sickly or deformed male babies were flung off the slopes of nearby Mt Taygetos. Perhaps because of male infanticide and early death resulting from the concurrent brutality in both military training and the subsequent battles that ensued, Spartan females oftentimes outnumbered their men. As a result of the imbalance coupled with seeing their husbands sporadically, it was not uncommon for wives to be shared amongst Spartan men. In a process known as wife sharing (or husband doubling), a married man could allow another man to father his wife’s offspring. The sharing of a wife’s reproductive potential was most commonly found in households where the wife was known to produce healthy children. The state both encouraged and endorsed such “wife sharing” as multiple husbands increased the possibility of healthy offspring, a long time Spartan goal.

This arrangement is in marked contrast to the patriarchal precepts found throughout much of the Greek world where husbands had exclusivity to the reproduction ability of their wives. Furthermore, if a woman had two husbands, she was in charge of managing two households and unlike in the rest of the Greek world, Spartan women were allowed to own land. In a state where the death rate of its men is higher than that of its women, the chance for inheritance was greater than average for women. And, in another departure from the Greek world, unmarried sisters shared in patrimony alongside their brothers. Aristotle once quipped that Spartan women owned 2/5th of the land in Sparta. Although the accuracy of this figure may never be known, the fact that women could own land was a big step toward their independence.

Was it because of this independence from the yoke of traditional patriarchy that Spartan women were derided throughout the rest of the Greek world? Time and again Aristotle ridiculed them for being the opposite of the feminine ideal found in neighboring Athens and ranted that Spartan women dominated not only their sons but their husbands as well. Intriguingly, the brazen characteristics of Spartan women mirror the most famous of them. Not only did Helen unabashedly leave her husband for another man, but no punishment was meted out to her. Indeed, after the long, bloody, ten-year war, her militant husband peacefully took her back to their quiet domain. In the end, Helen of Sparta had more power than any of the women in The Iliad. It is an irony that in a state that focused on the patriarchal precept of martial aggression, Spartan women controlled more resources and enjoyed more freedom than women elsewhere in the Greek world. From ancient to modern most sources agree, all things considered, Spartan women had authority and were subjects in the stories of their own lives.

Published on Classical Wisdom