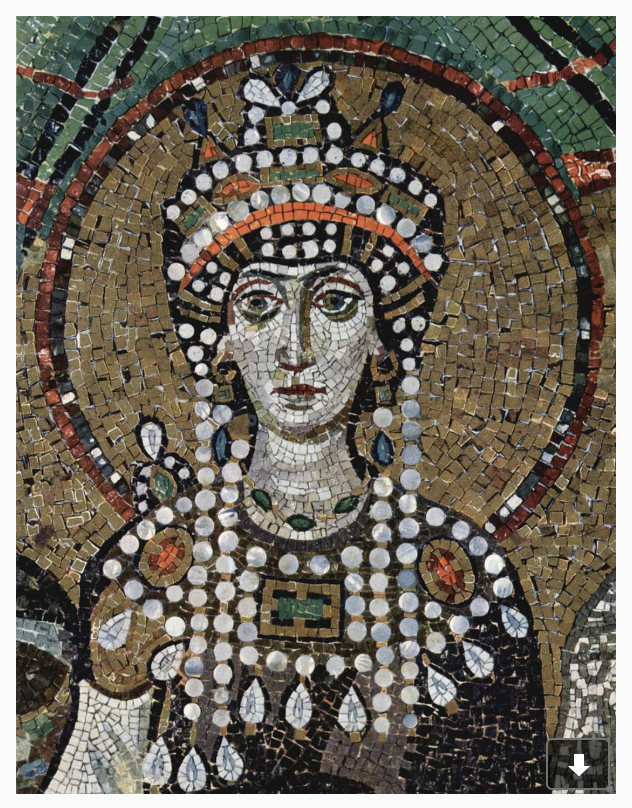

One of the most influential and powerful empresses of late antiquity, Theodora’s (c 497-548) life reads like a melodrama where she plays many roles: actress, prostitute, empress and posthumously, saint. Yet in in an era not known for social mobility, how did a humble actress-prostitute rise to the highest office of the land? Her beginnings greatly contrasted her subsequent status. Her father, a bear keeper worked at the Hippodrome and died when she was eleven. In a state of financial desperation, Theodora’s mother encouraged her three daughters to perform on stage.

In sixth century Constantinople, theater was the quintessence of depravity. Indeed, there was little difference between actresses and prostitutes; both were outcasts of society. To be sure, besides exposing themselves on-stage, actresses were required to provide sexual services off-stage as well. Ever a quick study, Theodora achieved notoriety as a comic actress and captured the attention of many, eventually moving out of Constantinople to become the live-in mistress to a wealthy governor in a North African province.

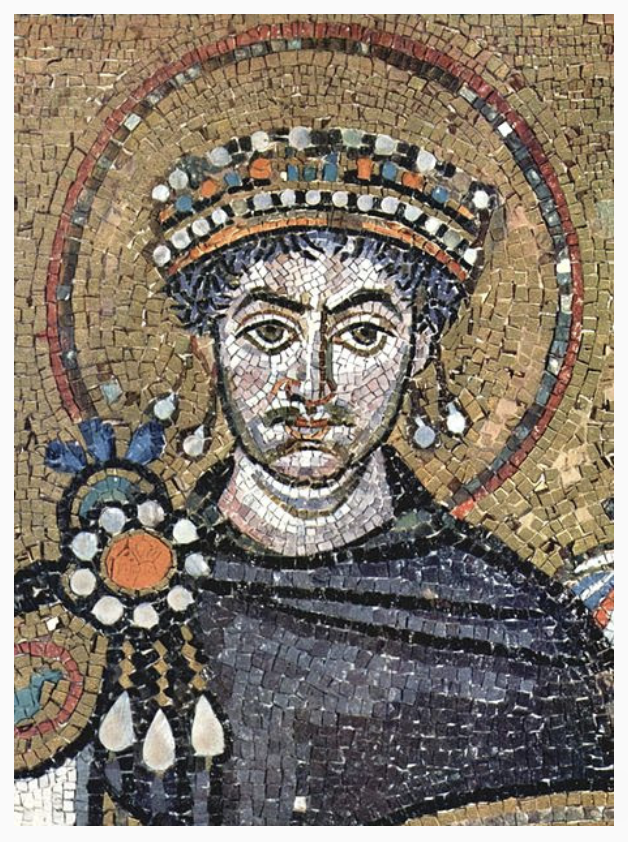

Sometime after the relationship with the governor soured, Theodora moved back to Constantinople in 522 where she met Justinian who soon fell under her spell. Unable to marry on account of a law that prohibited nobility from marrying actresses, Justinian entreated his uncle, then Emperor Justin I (c 450-527) to intervene. But because Theodora had been an actress-prostitute, Justin’s wife, Euphemia, opposed the marriage and persuaded Justin from assisting his nephew. After the death of Euphemia in 524, Justin I conferred nobility on Theodora thereby paving the way for Justinian and Theodora to marry. Because of Theodora’s background, the marriage sent shockwaves throughout Byzantine aristocracy.

In ill-health, Justin crowned both Justinian Augustus and co-emperor and Theodora Augusta in 527. Justin I died a mere four months after the crowning ceremony.

From the beginning, Justinian’s court became notable for the groveling it required from visitors—regardless of rank—something that did not bode well with the elite. Indeed, all guests were expected to prostrate themselves face down with their lips touching the imperial feet of not just the emperor but of Theodora as well. Reveling in the pomp and circumstance of being a royal, Theodora expected every sign of deference awarded the emperor. Though never co-regent, Justinian considered Theodora his partner in power and openly acknowledged that he consulted with Theodora on many issues.

First and foremost, Theodora wanted to be known for helping the unfortunate, especially women in need. Because of her background, her special concern was prostitution. She fought against the purveyors and helped rid Constantinople and cities throughout the empire of brothel keepers for whom prostitutes were virtual slaves. She orchestrated the building of the Convent of Repentance, which housed and supported former prostitutes. She and Justinian set up an endowment that added ancillary buildings to the convent complex. In addition to buying them new clothes, Theodora made monetary contributions to the women. The goal was for the women to live moral lives in relative comfort so they would not be tempted into a life of prostitution again. At the start, Justinian came to rely on Theodora’s keen intellect and political acuity, making her his most trusted advisor. But it was not until the winter of 532 that Theodora showed him her steely will and strength of character.

In an event known as the Nika (Conquer) Revolt two sparring factions, the greens and the blues, became united against Justinian ostensibly on account of his refusal to pardon convicted felons in each of their camps. Ultimately the rebels rioted and burned down more than half the city focusing on religious and imperial buildings such as the Hagia Sophia. Lacking anything resembling a modern police force, the emperor turned to his militia who were not trained to quell street protests and were soon overcome.

Spiraling out of control, the crisis had become so bleak that the Senate was debating not how best to remove the rioters – but how best to remove the royals. Meanwhile, Justinian and his retinue were holed up in the imperial palace planning their exit strategy. The generals and Justinian were in agreement that fleeing Constantinople in a boat under cover of night was the best way to save themselves. But Theodora had other plans.

Ever the actress, she took center stage with a stirring speech that roused both the emperor and his attendants changing the course of history: “While it is the condition of our birth to die, it is unendurable to descend from imperial power to the state of a fugitive. God forgive that I should ever be without this purple robe; may I not outlive the day when I cease to be greeted as empress! If safety is what you want, my emperor, it’s easily had. We have plenty of money; there’s the sea; there are our ships. But look out that when you are safe, you don’t discover that death would have been preferable. For my part, I like the ancient maxim, ‘Kingship makes a good burial shroud.’ “ Ever purposeful, the most esteemed Augusta had no enthusiasm for returning to the life of a commoner. It would take more than a riot that burned down half of Constantinople to remove the imperial purple from her grasp.

Moved to action by Theodora’s compelling speech, Justinian and his generals, Belisarius and Mundus, concocted a last-ditch effort to lure the rioters into the Hippodrome by spreading a story that Justinian would be there. Once the rioters were at the Hippodrome, the soldiers sealed off the exits killing the rabble-rousers and anyone else who crossed their path. Ultimately, it was the mass slaughter of tens of thousands at the Hippodrome, which is credited with saving Justinian and Theodora’s reign. Approximately thirty-five to forty thousand people perished in the massacre. One anecdote revealed that the riots were an outcry against the sovereignty of Theodora who upset the social order by marrying Justinian. Further, it was believed that the nephews of Justin I’s predecessor, Anastasius I (431-518), led the rioters. Stories vary on how the nephews, Hyaptius, Pompeius and Probus were brought to justice but most historians concur that Justinian showed leniency while Theodora—notorious for a ‘take no prisoners’ approach—insisted on their executions.

Although Theodora’s authority was considerable before the Nika Revolt, her greater influence afterwards may be reflected in many of the reforms Justinian put forward on behalf of women. In 534, Justinian prohibited anyone from coercing a woman, slave or free, from working in the theater if she was unwilling or to impede her if she chose to leave the theater. In another law with enormous implications Justinian vindicated the rights of women to own property and to inherit. Further, anti-rape legislation was passed in addition to laws supporting young girls who had been sold into sexual slavery. Finally, he protected the rights of women in marriages and betrothals. Indeed, her power was so considerable in getting the legislation put through that Theodora is mentioned in nearly all the laws passed pertaining to the rights of women.

While most scholars cast Theodora as neither sinner nor saint, it is interesting to note that Theodora was canonized in 2000 by the Patriarch of Antioch, head of the Universal Syrian Orthodox Church—a church the empress helped found.

In the end all her political maneuvering for determining successor to the throne came to naught. Her time on the planet was cut short, although fifteen years his junior, Theodora predeceased Justinian by seventeen years. In one of her biggest defeats, at the time of her death, Justinian’s cousin Germanus –her arch nemesis and chief adversary – was slated to become the next heir. It is an irony that the superlative power couple credited with ushering in one of the most productive periods of the Eastern Roman Empire themselves produced no children. Of the disappointments in her life, not bearing Justinian’s heir must have been the greatest. When Theodora was on her deathbed in 548, the ever-devoted Justinian was by her side promising to fulfill her last wishes and continue championing her causes.

Published on Classical Wisdom