For thousands of years, women everywhere have had Penelope to thank for playing the indelible role of a loyal and stalwart wife to Odysseus, her devious, vengeful and violent-prone husband. Displaying a keen intelligence and an unwavering constancy for endless hard years, Penelope is often depicted in the epic as weeping and wailing while she confines herself to the bedroom during critical moments—apropos of any intelligent and strong woman. Despite the Odyssey’s blustering androgyny, Penelope serves as the moral center and embodies the fundamental decision upon which the epic hinges. As she navigates the difficulties faced by women in an intensely patriarchal society, Penelope’s cunning can be as calculating as her husband’s, and her ingenuity as unwavering as her loyalty. So how can we understand Penelope’s multifaceted character—from her origins to her autonomy? And what does it mean in relation to her fidelity and its significance in Homer’s Odyssey?

Penelope of Sparta

Although she was introduced in the Odyssey as married for over 20 years, Penelope began her life in Sparta, the city-state that later became renowned for its martial excellence. Of royal lineage, Penelope was the daughter of Icarius, a prince of Sparta and brother to King Tyndareus, who was the father of Helen of Troy and Clytemnestra of Mycenae—her two defiant cousins with whom she stands in stark contrast. Like most young Greek brides, Penelope was between fourteen and sixteen years of age upon marriage to Odysseus who was likely several years or more her senior. Initially, Icarius disapproved of Odysseus as a suitor for his beloved daughter, however Tyndareus, seeking to forge greater strategic ties, assisted Odysseus in winning a foot race, which subsequently improved Icarius’s opinion of him.

Nevertheless, this did not stop Icarius from wanting Penelope to stay in Sparta after her marriage. He followed the bridal couple in his chariot pleading with Penelope to remain. Odysseus offered Penelope the choice to accompany him willingly to Ithaca or return to her father’s home, and in response, Penelope remained silent and lowered her veil, a gesture that indicated her decision to leave with Odysseus. In ancient Greece, the act of lowering the veil symbolized modesty, chastity, and loyalty—qualities that Penelope possessed in abundance. To demonstrate her modesty, in the epic Penelope is always depicted as holding a gleaming veil before her face when confronting her many suitors.

Icarius’s request for Penelope to remain in Sparta is indicative of the important role royal daughters, such as Penelope, played in maintaining dynastic ties and influencing political power within their states. Moreover, because of the clout they wielded, royal women often served as bargaining chips in diplomatic relations with other states, as illustrated by Penelope’s marriage to Odysseus, the king of Ithaca. This is substantiated by epigraphic and archaeological artifacts which give us a clearer understanding of the powerful royal women who held considerable wealth and influence during the Homeric Age.

Tell Me of a Complicated Man

Known as the cleverest of the Homeric heroes, Odysseus was responsible for dreaming up the Trojan Horse, which ultimately led to the fall of Troy and secured a Greek victory. Following that decade-long War, Odysseus embarks on a tumultuous ten-year journey back to Ithaca, during which he encounters mythical creatures, divine obstacles, and romantic entanglements with alluring goddesses. Despite his many adventures, Odysseus is eager to return to his wife, even rejecting the immortality that was offered to him by the enchantress Calypso, with whom he spent seven of those ten years. Instead, he chooses to grow old with Penelope and to endure the flawed impermanence of a finite life. About marriage, he famously advises:

“So may the gods grant all your desires, a home and husband, somebody like-minded. For nothing could be better than when two live in one house, their minds in harmony, husband and wife. Their enemies are jealous, their friends delighted, and they have great honor.” But for all Odysseus’ merits he is a morally ambiguous character who is deceitful, manipulative, and violent-prone, often using trickery and disguise to achieve his goals. This, in turn, renders him an unreliable narrator in the story of his struggles. In the epic when the poet sings, the audience can be assured of its veracity; when Odysseus recounts events—especially in Books Nine through Twelve—skepticism is advisable.

Penelope’s Efforts

Meanwhile, in Ithaca, a desperate Penelope—who like all wealthy Greek wives is confined to her home—laments the long absence of her husband while successfully managing a royal household, raising their increasingly rebellious son (Telemachus) single-handedly, and resisting the advances of one hundred and eight aggressive suitors eager to marry her and usurp Odysseus’s throne. For nearly four years, the suitors intrusively invade her home and attempt to coerce her into marrying one of them, aiming to take control of Odysseus’s realm. Not only do they bully Penelope, but they also display disdain and immorality by violating the ancient Greek principles of hospitality (xenia). They consume the household’s resources; without sacrificing to the gods, they slaughter the livestock, and behave rudely toward both servants and guests, all while jeopardizing Telemachus’s inheritance by depleting the family’s reserves.

From the beginning, it is clear that the issue that is central to the Odyssey is the situation at home and Penelope’s critical role in it. It has been twenty years since Odysseus left Ithaca, yet before he departed, Odysseus told her: “When you see our son grown up and bearded, then you may marry whatever man you please, forsaking your household.”

While the decision to remarry is portrayed as all-important throughout the epic, the agent of this decision is ambiguous. At times, it rests solely with Penelope, while at other times, it involves either her son, her father, or both. Regardless, since no one claims the authority to force her into remarriage, the final decision ultimately lies with Penelope, whose choice will not only influence her destiny but Odysseus’s and the lives of those around them.

A Bearded Son

Although she has Odysseus’s permission from two decades ago to enter another household and seek a new marriage, Penelope hesitates. Throughout the epic, she grapples with essential questions: Is her husband alive or dead? Is she married, or is she a widow? With her son now fully grown and bearded, Penelope’s role has become less indispensable. While the audience is aware that Odysseus is alive, she remains one of the last characters to discover his return to Ithaca. These questions linger until nearly the very end. Nevertheless, her hesitation to act is jeopardizing her son’s inheritance, and as he matures, he becomes increasingly restless and insubordinate.

Book One offers the audience a glimpse at family dynamics, revealing Telemachus’s eagerness to assert his authority when he scolds his mother for requesting that a bard refrain from singing a nostalgic tune that saddens her because it reminds her of her long-lost husband. According to classicist Mary Beard, Telemachus’s rebuke is the first recorded instance of a man telling a woman to be silent in literature: “Mother, no, you must not criticize the loyal bard for singing as it pleases him to sing… Go and do your work; stick to the loom and distaff. … It is for men to talk, especially me. I am the master.”

In response, Penelope obediently retreats to her bedroom, weeping for her absent husband.

Clever Penelope

For all her obsequity, however, Penelope is not without guile. The audience witnesses her cunning in Book Two when Antinous, a prominent speaker for the suitors, recounts her flirtatious trickery to Telemachus:

“She offers hope to all, sends notes to each…” “Young men, you are my suitors. Since my husband, the brave Odysseus, is dead, I know you want to marry me. You must be patient; I have worked hard to weave this winding-sheet to bury good Laertes when he dies.”

Under the pretext of completing the funeral shroud for her father-in-law, Laertes, she weaves a tapestry by day, only to unravel it at night. This deception continues for over three years until a maidservant reveals the truth, and the suitors become aware of her ruse. Ultimately, they force Penelope to finish the shroud and demand that she choose one of them. Antinous concludes his speech to Telemachus by telling him that until she selects a husband, the suitors will not return to their farms, and his wealth will continue to be consumed.

The Trouble with the Suitors

Consuming his wealth, however, is not the only way that the suitors could harm Telemachus. In Book Four, Penelope becomes aware of a plot to kill her son when her herald tells her: “The suitors want to kill Telemachus with sharp bronze weapons on his journey home.”

Poor Penelope is always the last to know about important events. Not only has she never heard of the plot to kill her son before, but she is also the last to know about Telemachus’s journey: “And now the winds have taken my dear son, and no one told me that he was setting out. Shame on you all!”

In characteristic Penelope fashion she weeps and takes to her bed. Athena, in the guise of a phantom, visits Penelope to offer solace, but, despite the goddess’s awareness of Odysseus’s survival, she suppresses this information, leaving Penelope ignorant about Odysseus’s survival for an additional nineteen books.

In Book Eighteen, Penelope enchants the suitors with her coquetry, supported by Athena, who amplifies her allure. Upon confronting the suitors she signifies modesty; nonetheless, her subsequent actions suggest that there may be complexities beneath her exterior: “She reached the suitors and stood beside the central pillar, holding her gauzy veil before her face. The suitors weakened at the knees; desire bewitched them, and they longed to lie with her.”

Although nowhere in the epic does it imply that Penelope has been unfaithful to her husband, she is not without her feminine wiles which she uses to her advantage.

After captivating the suitors with her beauty, once again she cleverly manipulates them. This time she asks for ‘splendid gifts’ from them to test the suitors’ sincerity and strength or so she tells them. But more importantly since the weaving and unweaving of Laertes’s shroud has been detected, the request for presents is yet another tactic to buy time and to distract the suitors from increasing pressure to marry her.

The Return of Odysseus

In Book Nineteen, Penelope converses with Odysseus, who is disguised as a beggar. Unaware of his true identity, their conversation is filled with longing and nostalgia, as Penelope reminisces about her husband and shares her sorrow over their extended separation. Moreover, the beggar tries convincing her that he knows Odysseus and assures a bereft Penelope that her husband is coming back soon: “I tell you he is safe and near at hand. He will not long be absent from his home and those who love him.”

The exchange between the two concludes with Penelope’s proposal for an archery contest, where the winner will earn her hand in marriage: “I will assign this contest to the suitors. Whoever strings his bow most readily and shoots through all twelve axes will win me. And I will follow him.”

Is Penelope’s creation of the bow contest a sign of her infidelity, as some suggest? Or is it merely another stalling tactic to delay the suitors? While several characters in the epic, including Odysseus’s old dog, Argos, have become aware of Odysseus’s true identity, Penelope remains unhappily uninformed. Believing herself to be a widow and focused on protecting Telemachus’s inheritance, at long last, she may be prepared to remarry.

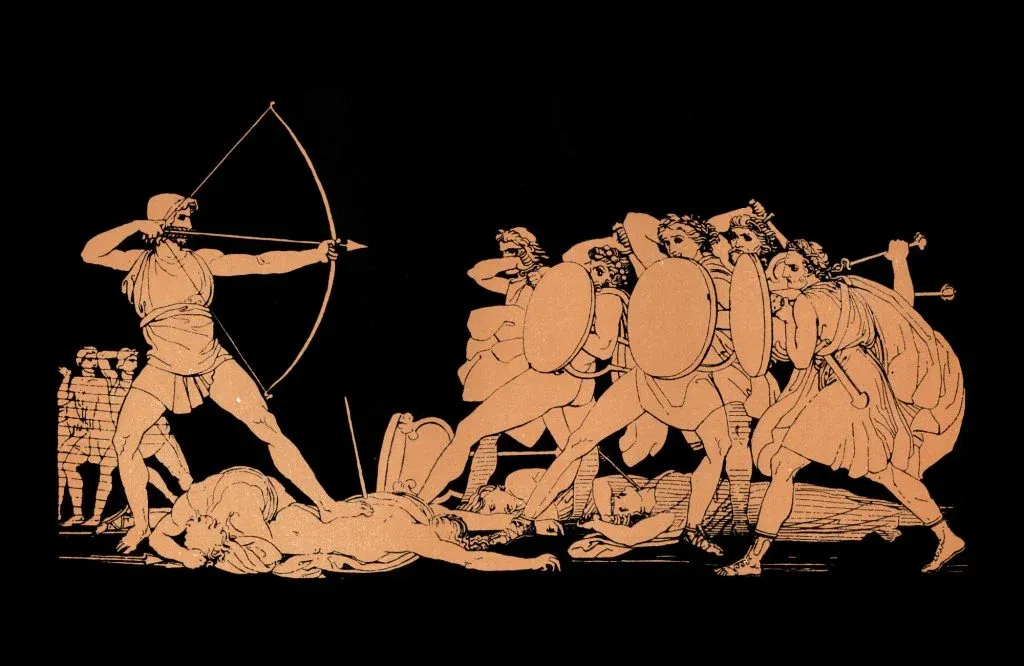

Ever the cunning strategist, Odysseus, who had previously triumphed in the bow contest, cleverly urges Penelope to hold it without delay. This competition initiates the events that ultimately lead to the suitors’ bloody demise. After winning the contest, the Greek hero kills all one hundred eight rivals.

Although Odysseus reveals his identity to Telemachus in Book Sixteen, he does not disclose it to Penelope until the penultimate Book Twenty-Three, after the slaughter of the suitors. By not revealing himself to her, Odysseus follows the advice of his old friend and comrade Agamemnon, whose cynical shade advises him in Book Eleven: “When you arrive in your own land, do not anchor your ship in full view; move in secret. There is no trusting women any longer.”

The backstory is that after ten years of fighting in the Trojan War, Agamemnon returned home, only to be brutally murdered by his wife, Clytemnestra, along with her lover, Aegistus. Odysseus, who has been away twice as long, has absorbed his friend’s deep skepticism about women thus he is reluctant to present himself to Penelope. In his book Greek Myths, Robert Graves argues that Odysseus does not fully trust Penelope, which is why he waits until he has eliminated all one hundred and eight suitors and potential rivals before he reveals himself to her.

The Ruse

Odysseus is not the only one who distrusts his spouse. In Book Twenty-Three, Penelope is uncertain whether Odysseus is truly who he claims to be. To test him, she decides to ask about a personal detail only he would know. She instructs her maid Eurycleia to move their bridal bed, fully aware that Odysseus would understand the impossibility of this task, as the bed is constructed around a living olive tree. The hot-headed Odysseus responds angrily:

“Woman! Your words have cut my heart! Who moved my bed? It would be difficult for even a master craftsman—though a god could do it with ease. No man, however young and strong, could pry it out.”

He then pointedly questions her fidelity, demanding, “But woman, wife, I do not know if someone—a man—has cut the olive trunk and moved my bed, or if it is still safe.”

The scene evokes the Greek hero’s propensity toward violence, as it comes directly after his bloody massacre of one hundred and eight suitors and the disturbing image of the hanged bodies of the twelve so-called wayward maidservants he commanded his son to execute. We are reminded in this hyper-patriarchal culture that violence toward women was not uncommon. Could Penelope face harm if Odysseus views her as a wayward wife, as his pointed questioning suggests?

Now fully convinced he is Odysseus, quick-thinking Penelope is able to assuage his anger by apologizing for ever having doubted her master-deceiver husband:

“Do not be angry at me now, Odysseus! In every other way you are a very understanding man…Please forgive me, do not keep bearing a grudge because when I first saw you, I still would not welcome you immediately.”

All is forgiven, and trust is restored for the star-crossed couple. After twenty years, they are reunited in a relationship borne of a shared history and common goals. The metaphor of their matrimonial bed built around a living olive tree symbolizes the vibrancy of their marriage. Just as the tree grows, this “like-minded couple” will also grow old together, united in a harmonic marriage that is a living entity designed to thrive.

Penelope the Autonomic

Greek women must have envied the agency Penelope displayed throughout the epic. After all, they rarely had the autonomy to select their spouses or to choose whether or not to remarry. Steadfast and resolute, Penelope stubbornly dismisses the notion of being a mere commodity that is exchanged between the suitors and her son, Telemachus, or her father, Icarius. Despite the weepy acquiescence she exhibits during the course of the poem, Penelope maintains her independence and ultimately earns respect from both the suitors and Odysseus. Her strength lies in her unwavering dedication, enabling her to cope with the obstacles in her life with grace. While it may not have been Homer’s intention when he created her character, Penelope’s subtle resistance within a patriarchal society illustrates the endurance of women in the ancient world, even when their stories frequently go unheard.