“Let her be banished for life,” Augustus (63 BC-14 AD) is recorded as saying about the harsh exile of his only biological child, Julia, to the barren and windswept penal island of Pandateria (present-day Ventotene). Banishment from Rome, however, was not enough for the wayward princess. The emperor further decreed that aside from the guards who kept watch, no men were allowed on the island. The implication being that for a woman of loose virtue, being deprived of male companionship would make for a more exacting punishment. To that end, wine was forbidden on that stygian enclave and food provisions were at a mere minimum. In other words, Julia was in prison.

The Merry Widow Banished

Adored within the palace and outside of it, Julia (later Julia the Elder) was charismatic, sophisticated, and renowned for her joie de vivre. When word of her banishment got out all of Rome was in an uproar. No one had foreseen that even a wet blanket like Augustus was capable of exiling his only biological child. In an attempt to restore their adored princess, whom they lovingly referred to as “the merry widow,” the people came out in droves for her. They packed the streets with noise and rancor holding effigies and calling for her release. An indifferent Augustus decried: “Fire will sooner mix with water than that she shall be allowed to return.” In a playful retort the people threw fiery torches on the Tiber. The emperor was not amused. He charged: “If you ever bring up this matter again, may the gods afflict you with similar daughters or wives.” Not soon forgotten, the protests continued even five years after her exile.

Over these long millennia, Julia’s reputation has been maligned by ancient writers and contemporary historians alike, but was it something more than loose morals that set her father against her? Make no mistake, being labeled a woman of ill-repute was reason enough to land Julia on the prison island during the authoritarian Augustan era. All the same, according to Suetonius, Augustus debated putting his daughter to death. “I had rather be the father of Phoebe than of Julia,” Augustus bewailed after Julia’s freedwoman, Phoebe, committed suicide over her mistress’s scandal. Considering the severity of her father’s reaction, some believe that Julia’s fall was due to her involvement in a political intrigue to overthrow him. But why act against her better interests when her two eldest sons were adopted by Augustus and primed for the throne? One can explore the possible reasons behind Julia’s harsh exile by delving into the politics of the era and the climate of paranoia and suspicion within the Julio-Claudian clan itself.

……………………………

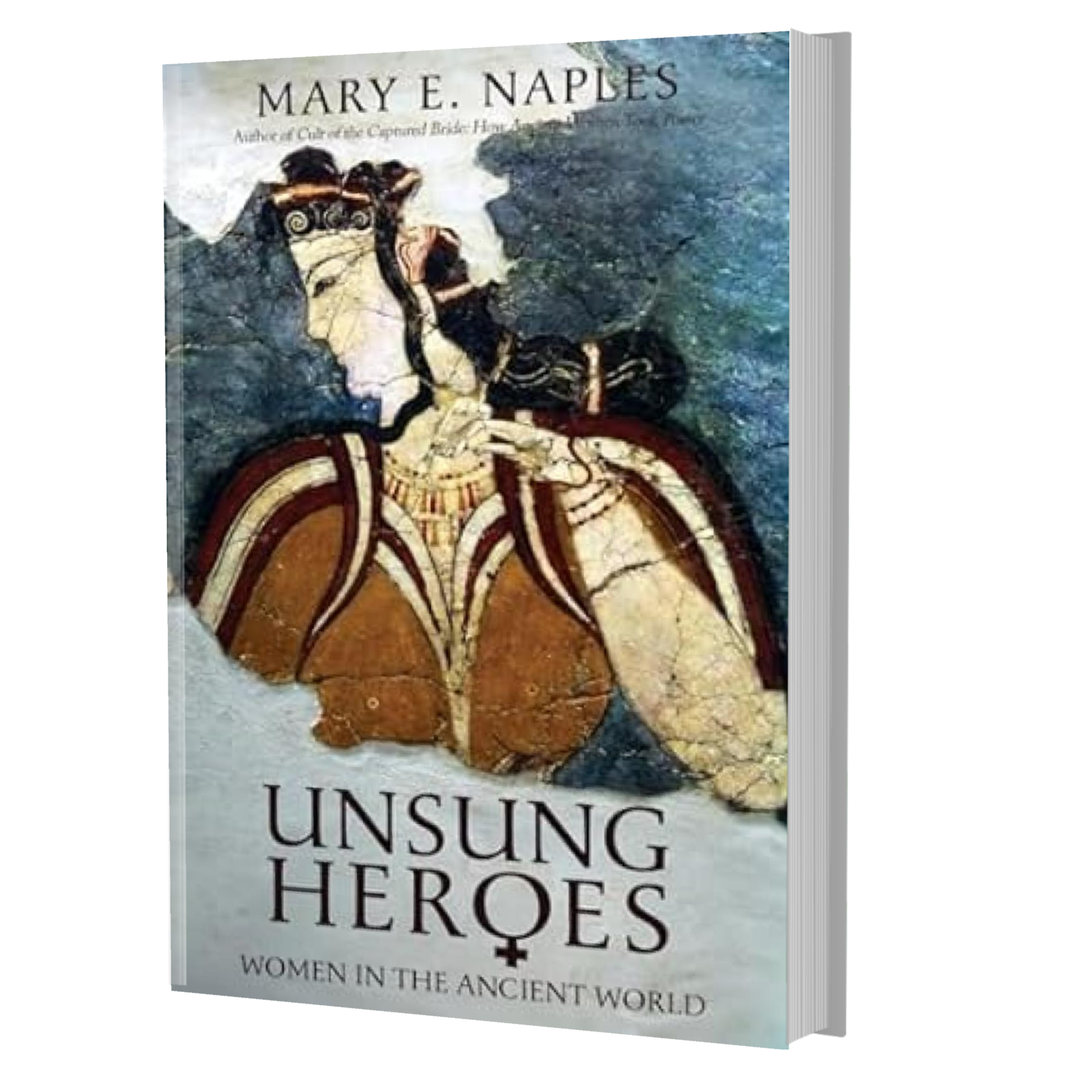

What crime would have induced Augustus to exile his only biological child? Find out in my book Unsung Heroes on Amazon.