“They would not listen, they’re not listening still. Perhaps they never will.”

—Don McLean “Vincent”

With a name that defines incredulity itself, it is no wonder that Cassandra—the cursed Trojan prophetess—has a hard time being taken seriously. Scorned throughout the ages, Cassandra was infamously disregarded and frequently reviled by her countrymen. Even her own mother ridiculed her. Today she has a psychiatric syndrome named in her honor for those suffering from undue hysterical negativity. In short, she gets no respect. But why such indignation toward her?

If her compatriots had heeded her guidance, the Trojan War might have ended differently for them, or it may not have begun at all. It was Cassandra, after all, who foretold the demise of Troy on account of a trip to Sparta made by her errant brother, Paris. In one tradition, she even suggests that her parents kill him as an infant—-which in hindsight may have been sage advice.

What is more, she predicts Troy’s destruction if they accept the gifted horse, “But by god’s will, Troy would never listen.” Although always disbelieved, her dire predictions were spot on. Even so, there is no point in being an incredulous prophetess. So how were other soothsayers treated in ancient Greece? And what about another priestess of Apollo—-the most highly revered Oracle of Delphi? How was Cassandra’s form of soothsaying different from those of her historical contemporaries?

Born a Trojan princess to King Priam and Queen Hecuba, Cassandra’s early life was one of privilege. Though she was famed for being a virgin priestess to Apollo, virginity, in the ancient world, had more than one meaning. Besides signifying chastity, it could highlight and draw attention to the fact that a woman was not married. Markedly, Cassandra never married… and so perhaps this was reason enough to distrust her. After all, she was a free agent. No man had any authority over her.

……………………………

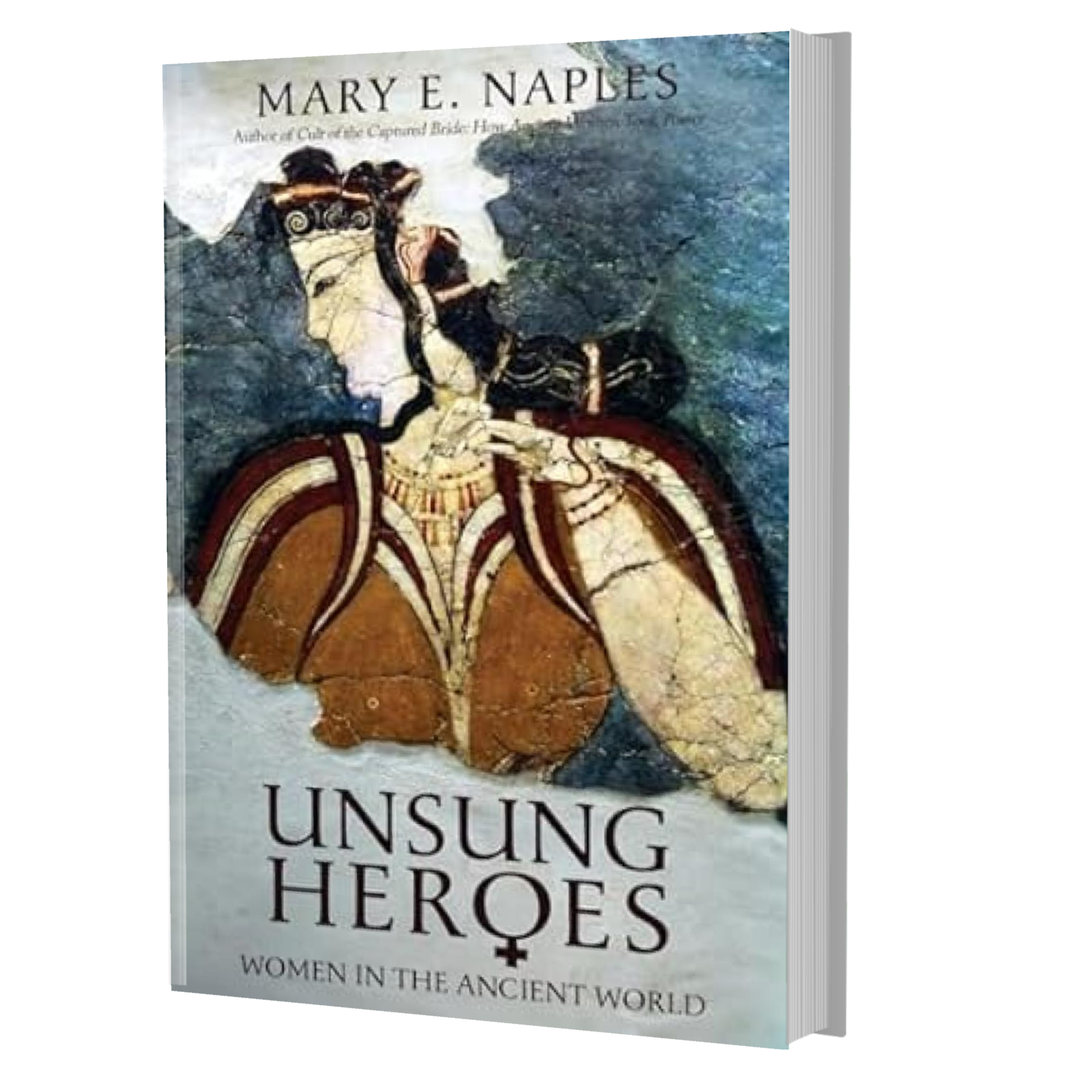

How was Cassandra’s form of soothsaying different from her soothsayer peers whose every word was obeyed? Read more in my book Unsung Heroes on Amazon.