It was love at first sight when Achilles locked eyes with the famed Amazon warrior queen, Penthesilea. Romance, however, was the last thing on his mind. Alas, poor Penthesilea—Achilles would realize his love for her only after driving a bronze spearhead into her chest.

Unquestionably, this mightiest of Greek heroes was felled once her helmet was lifted revealing Penthesilea’s savage beauty “undimmed by death.” The Aethiopis reports that Achilles suffered pangs of mourning as intense as those he felt from the loss of his beloved Patroclus. But Achilles was not alone among Greek heroes to battle, then fall for an Amazon.

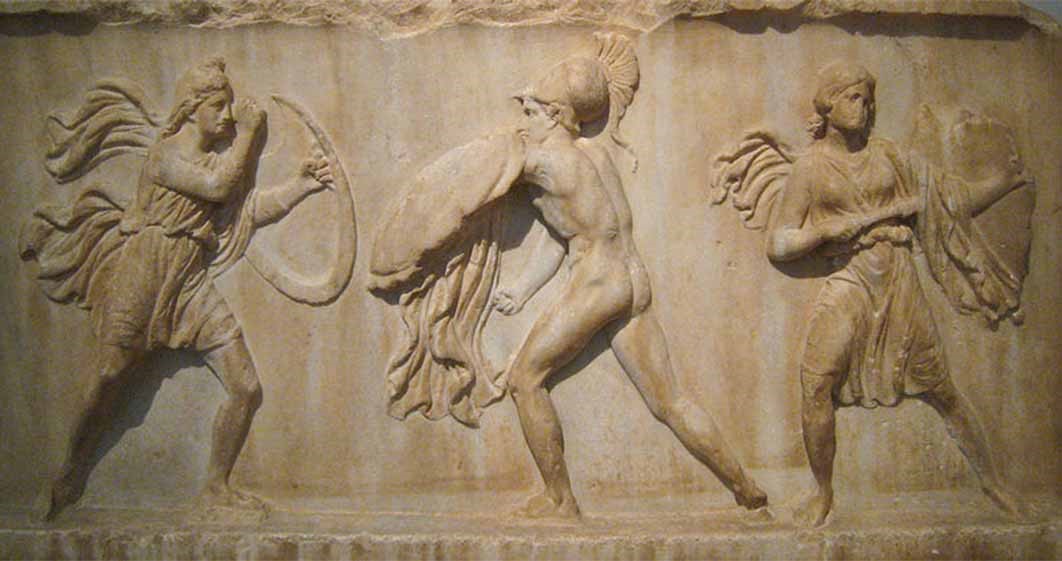

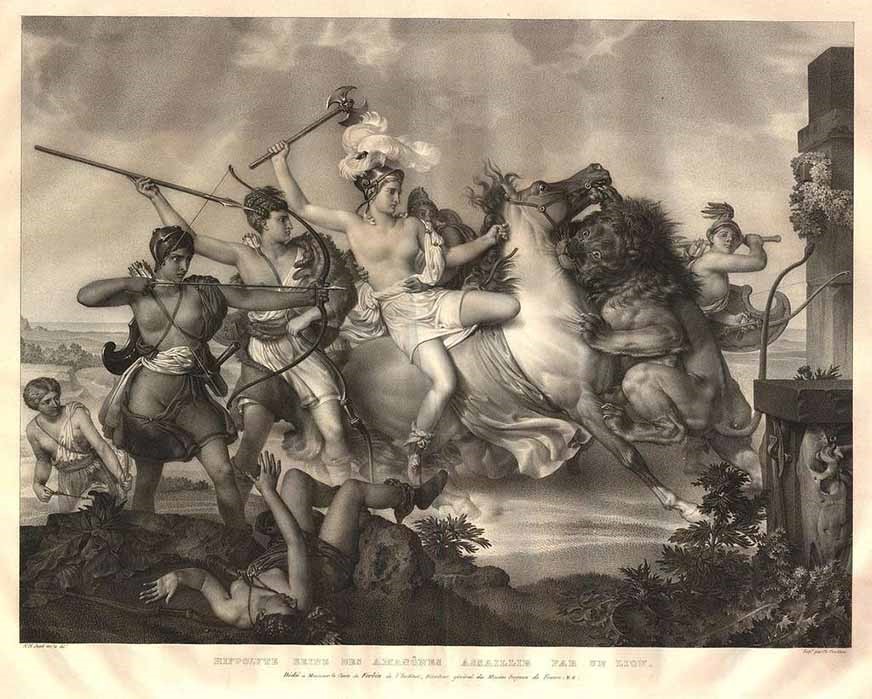

Combatting Amazons was a yardstick with which to measure the bravery of Greek heroes. During a vignette that sounds suspiciously like rape, in the ninth of his twelve labors, Heracles was forced to strip the magical “war-belt” or girdle off the warrior-queen, Hippolyta. Unsurprisingly, it did not go well for the Amazon queen. Evidently unaware of his own brutish strength, the mighty Heracles, while attempting to disrobe Hippolyta, wound up killing her instead. Finally—according to one tradition—Theseus, the mythological first king of Athens, battled then married yet another Amazon queen, Antiope, who would become queen of Athens sparking a war between the Amazons and the Athenians, termed Amazonomachy (Amazon battle). Predictably, the Amazons were routed. In each of these tales, although defeated, the Amazon is treated honorably at the hands of a Greek hero; or in the case of Antiope, is treated no less than a Greek woman—about as much as the fairer sex can expect from a Greek man.

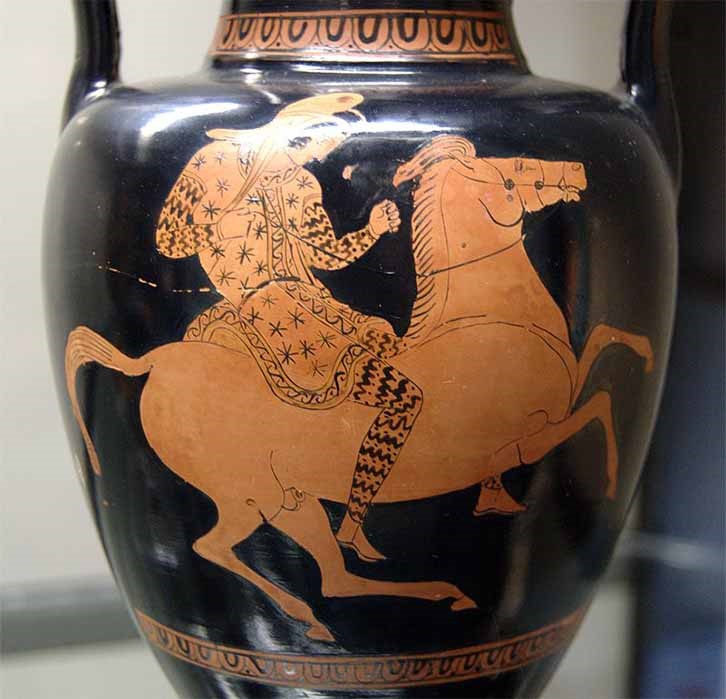

Renowned for their courage and bravery against Greek heroes and gods alike—Amazons were a notorious force with which to be reckoned. In fact, their popularity even made them a subject in artwork and statuary adorning public, private, and sacred spaces across the Greek world. Their ferocious personas were often depicted sporting pants and hurling javelins from the seats of their attendant steeds. Perhaps the fame of the Amazons could be due, in part, to their being antithetical to everything the Greeks held dear in womanhood. After all, for the hyper-patriarchal Greeks, there was no culture in the ancient world—regardless of how diverse—that represented “other” more than the combatant, independent, male-hating Amazons. This could help explain why in vase art Amazons were second only in popularity to the colossal Heracles himself. Moreover, even children were influenced by them; dolls depicting Amazons’ distinctive headgear have been found in the graves of young girls throughout the Greek world.

Steeped in Greek culture, Amazons were acknowledged by none other than Plato as the “equals of men” and reported as historical fact by the ancients. Since then, however, scholars have considered Amazons to be in the realm of mythology. Who could blame them? After all, the notion that the weaker sex could be on an equal footing in battle against male counterparts seemed too absurd to be believed. Since the emergence of DNA testing, however, it has been determined once and for all that the Amazons were not a figment of the Greek’s fertile imagination.

At first glance, there is nothing unusual about the remains of a young warrior approximately twenty to thirty years of age from the fourth century BCE. Like many warriors from the area, this one was buried with a collection of spears, bows, quivers, and bronze-topped arrowheads, along with an armed leather belt and various other instruments of war. As it happens, the most renowned amongst the nomadic horse people were often buried along with their steeds. A battle-ax smashed through the skull demonstrates the manner of this warrior’s death. When these bones were first excavated in the seventies, it had been assumed with some authority that these were the remains of a male warrior. But all that has changed. With the advent of DNA testing, it has recently been determined that this warrior was female. Yet as brave and daring as this young woman may have been, she was not an outlier. Thousands of burial mounds such as hers can be found from Bulgaria to Mongolia. In some areas fully thirty-seven percent of all warrior skeletons were those of warrior women. Could the ancients have been right all-along? Were the livid tales of a raucous band of male-hating female warriors, fact not fiction—as had long been supposed? After being erased from the annals of history, at long last—are Amazons finally being restored?

Most experts today believe that Greeks understood the women whom they referred to as Amazons were from a nomadic culture residing amongst a myriad of small tribes throughout a vast territory now referred to as the Eurasian Steppe. The wide swath of rugged landscape, known to the Greeks as Scythia, extended from Thrace to the west of the Black Sea across the steppe of Central Asia to beyond the mountains of Mongolia concluding at the Great Wall of China. In total, the land of the nomadic warriors encompassed nearly five thousand miles (or eight thousand kilometers) and shared borders with such ancient civilizations as Greece, Assyria, Persia, India, and China. It is unsurprising that skirmishes were not infrequent between the Scythians and their settled neighbors. Though the Greeks referred to the entire region as Scythia, it was also home to the ancient Sauromatian, and Thracian tribes much referred to in Greek writing. Indisputably, ethnicity was a fluid concept amongst nomadic tribes who roamed the vast steppe often interbreeding with each other. In fact, it is no coincidence that the area pinpointed as home to Amazons is also a region rife with the remains of ancient nomadic warriors. When archaeologists first began unearthing thousands of kurgans or burial mounds from the Eurasian region, they discovered that the nomadic culture dated back to at least the tenth century BCE.

Once they began breeding horses—around the ninth century BCE—Scythians flourished becoming famous for their mounted warfare. From 800-700 BCE when the Greeks first began colonizing the area around the peninsula of Anatolia—between the Aegean and Black Seas—Scythians and Greeks began having clashes. Not coincidentally this was the same time that the Amazons began to capture the Greek imagination. In the eighth century BCE, Homer was the first to consider them in The Iliad, which is set in the Bronze Age (2800 BCE- 1050 BCE) several hundreds of years before the epic was composed. Though only mentioned in hearsay, battling Amazons is referred to twice within The Iliad in books three and six, by Priam and Bellerophon respectively. Although the Amazons are roundly defeated by the heroes, in both cases the phrase “a match for men at war,” is used to describe them.

But it was not until the fifth century BCE, that Amazons rode into the historical account when Herodotus—the so-called father of history—chronicles their origins. According to Herodotus after the Greeks defeated the Amazons, they captured the survivors and set sail with them on three ships. It did not take long, however, for the Amazons to stage a mutiny killing all the Greeks on board then commandeering the ships. Unable to sail, the landlubbers met friendly winds that deposited them to an area inhabited by Scythians—on the northern coast of the Sea of Azov. After some minor skirmishes with the locals the Scythians soon became captivated by the female warriors—and mating ensued. One day the Scythians asked the women: “Let us head back to the main body of our people and live as they do. You are wives for us, you and you alone.” But the independent women wanted no part of an arrangement which would tie them down and replied: “We have never learned to do women’s work. We shoot arrows, throw javelins, ride horses.”

Finally, the women ask the young men “to go to their parents and take the due share of your possessions……to set up home together on our own.” Unlike in the Greek tradition where it was females who were expected to provide the dowry, in this case the dowry was provided by males. The Amazons and the Scythians would eventually leave the area forming a new tribe called the Sauromatians. In addition to dressing like their male counterparts, women were expected to ride, hunt, and go to war—just like men. Herodotus, however, not only demonstrates parity between the sexes—his account depicts a society where women are clearly in charge. In fact, marriage between the Scythians and the Amazons differs radically from the patriarchal notion of matrimony in the Greek world. Not only was it the men who were expected to provide the dowry, but it was the women who set the rules determining how they and their husbands were to live in their new society.

Over the years, Herodotus’s account of the Amazon myth and the origins of the Sauromatian people were considered to be in the realm of mythology but that all changed with the excavation of the Sauromatians’ burial mounds in today’s Volga and Ural regions. Like the burial mounds throughout the rest of the Eurasian Steppe, those of women were like those of men and included implements of war and articles of horsemanship. But in addition to fighting right alongside men, evidence suggests that women held the roles of chieftains and priestesses. Artifacts from their burial grounds have unearthed both material honors commensurate with positions of power and religious objects befitting priestesses. This has led some scholars to argue that their culture was matriarchal—or at a minimum, matrilineal—and that the cult of the mother goddess was worshiped in their society. In fact, it is believed that fertility goddess worship was widely spread within the Scythian region amongst the nomadic tribes.

Yet not all claims about the Amazons by Herodotus and other ancient chroniclers are backed up by archaeological artifacts. Herodotus begins his narrative with how Scythians referred to the Amazons as “man-killers” or in the Scythian language oiorpata. Popular in Greek lore, the presumption was that no Amazon was allowed to marry until she had slain a man in battle. Following closely on the heels of this premise was another which depicted Amazons as “man-hating” and “man-less” and characterized them as a savage all-female race who killed their males upon birth. To their being an all-female society, ancient historian, and geographer Strabo (64 BCE- 21 CE) incredulously asks, “who could believe that an army, city, or nation of women could ever be set up without men?” For all his misogyny, Strabo’s point is well-taken and appears to be backed up archaeologically. Though warrior women likely fought as a group, so far, no evidence supports that Amazons existed as a society solely onto themselves. Burial grounds from the region demonstrate that both male and female warriors lived together as a populace. Moreover, it is reassuring to note that to date no evidence supports the claim that Amazons killed their male infants.

While the Greeks hurled tall-tales and inuendo against the warrior women, they were not alone in writing about them. Harrowing legends about the bravery and fortitude of nomadic warrior women could be found in most ancient civilizations bordering the Eurasian steppes including Egypt, Persia, Caucasus, Central Asia, and China. The non-Greek tales about the Amazons, however, differ from their Greek counterparts in one significant way. Unlike the tales of defeated Amazons composed in the Greek tradition, in many of their stories, the Amazons successfully beat back their non-Greek rivals and live to tell the tale. Not only do the Amazons win in other traditions, but oftentimes they become allies and companions as well as lovers who survive the battles with their male counterparts. Because the Scythians themselves were a pre-literate culture, regrettably, ancient Greek and non-Greek sources have become relied upon to fill in the blanks about their lives.

Though the Scythian culture was without writing, it was not without stories. These stories, called the Nart sagas, were an ancient oral tradition of the Caucasus reckoned to be as old if not older than Homer’s famous epics. The sagas depict a race of warrior horsewomen who strongly resemble the Amazons. Largely independent from the yoke of marriage, these women were courageous and forthright; characteristics the Greeks attributed exclusively to the male gender. Furthermore, the sagas suggest a possible etymological link to the word Amazon itself. One of their vignettes portrays a famous Circassian queen called Lady Nart Sana or Lady Amezan also known as “Forest Mother or “Moon Mother” phonetically pronounced a-maz-ah-na in Circassian. Though quick to carve out an enemy’s heart, this story demonstrates how the battle-ready Amazons had a softer side as well. Resembling nothing less than Botticelli’s Venus, the beautiful Lady Amezan with her long undulating fiery red hair, was secretly in love with a handsome man from another tribe. But by a twist of fate, she discovers to her horror that the helmeted warrior she cut down in battle is none other than her secret beloved. Straightaway, Amezan rushes to his side, trying to resuscitate him by kissing his cold, lifeless lips. But it is too late. “My sun has set forever!” she cries before bringing down the sword on herself: “They lay dead together, Amezan and the man she loved.” According to the saga, a spring would surface where the earth absorbed the star-crossed lovers’ blood.

The name “amezan” is an example of the word in its native origin, but the Greeks had their linguistic equivalent of “amazon” as well. One persistent myth that has dogged the Amazons is the wrong-headed notion that the women had to cut off their right breasts to properly shoot an arrow. Most archaeologists now agree that there is no evidence to support Amazons cutting off their right breasts— or any breasts for that matter. Moreover, they were fully capable of slinging arrows with their breasts intact. Yet the myth of their only having one breast has endured throughout the ages. Why the tale? Perhaps the reason lies in the word “Amazon” itself. Broken down etymologically in Greek “a” means without and “mazos” means breast. Were the ancient Greeks trying to make the Scythian women look even more exotic than they were, putting a further distance between them and their secluded Greek counterparts? Considering how far apart the two cultures were in their treatment of the fairer sex, the chasm between Greek women and their nomadic sisters was wide enough already without the single-breasted fable.

It must have been astonishing for Greeks to discover the freedom afforded unattached nomadic women. After all, in the Greek world, girls no more than fourteen to sixteen years of age were often spirited away by their suitors—men who were frequently much older than they—and confined in marriage to their husband’s home where a life of subjugation and domesticity awaited them. In direct contrast, matrimony in the nomadic world was oftentimes a competition between males and females of approximately the same age. One account by the naturalist Aelian (175 CE -235 CE) holds that if there was an interest in marriage on the part of the male then he had to wage a battle with his beloved. Whereas most fights were to death, this fight was to betrothal with the winner seizing control of the reins throughout the marriage. Not rigged in favor of the male from the outset, in the nomadic world there was some parity between the sexes—a foreign concept to the ancient Greeks.

In fact, in the nomadic realm there was no set age for marriage, furthermore, nomadic women and men were free to comingle with each other before marriage and even to take on other lovers after marriage. Given that seasonal patterns are typical to the nomadic way of life oftentimes they migrated from pastures in the summer to camp-sides in the winter while springtime brought bands of tribes together as a means of forging alliances. In this way, intertribal unions were accepted and even commonplace. Before modern testing methods proved otherwise, many experts had opined that in most tribes, women were warriors until they had children at which point, they stayed with their kin. Modern scientific analysis, however, has disavowed that hypothesis. It has since been determined that many of the uncovered burial mounds were those of warrior mothers. Oftentimes they were buried alongside infants and children adding credence to the argument that in addition to being young and unmarried, Amazons were mothers too.

Daughters, lovers, wives, and mothers, although their titles were the same as their Greek counterparts, their roles were worlds apart. In comprehending an alternative way of life, Amazons were exemplars for girls and women throughout the Greek world. But why did the Amazons have greater freedom in their lives than the established Greeks? One reason may be that in the resource-scarce nomadic society, everyone was expected to pitch in to do his or her part. Indeed, scarcity became a great liberator as girls were trained right alongside boys in hunting and warfare. After all, females were just as effective at riding horseback, thrusting spears, and slinging arrows as their male counterparts. Furthermore, if the enemy should come calling there was no place for the women to hide. Frequently on the go, their makeshift shelters were flimsy and insubstantial. And because there were no cities, there were no surrounding city walls to protect the nomads from invading forces. All said, women—just like men—had to be battle-ready on a dime.

What, however, would become of a culture which demonstrated parity between the sexes? In the third century BCE, their independence declined, and Scythians fade from historical and archaeological records after about the second century BCE. In greatly reduced form, some claim they were ultimately assimilated into Slavic and Gothic tribes in the early centuries of the Common Era.

Brave, fearsome, adventurous, independent, and forceful, some of the adjectives used to describe Greek heroes could also be used to describe Amazons. In fact, compared to their treatment of people from other cultures, on balance, the Greeks were fair to the Amazons. This could be due, in part, to their enchantment with the warrior women. After all, DNA testing has shown that the women were tall, athletic, and fair-skinned—not unlike those who reside on the “heavenly threshold” of Mount Olympus. Perhaps their resemblance to goddesses could help explain their overall popularity within the Greek culture itself.

Through antiquity’s primordial haze, the warrior woman begins to take shape. Appearing out of the shadows, she rides high atop her majestic steed flanked in head-to-foot armor and wielding a jagged spear. Undoubtedly, a forbidding sight to every Greek she encountered. Advancing into greater focus, her imposing presence, once hidden in obscurity, is gaining in clarity as never before. Thanks to modern scientific methods—Amazons are moving from the margins of mythology into the terra firma of historical fact. Even so, examining a preliterate culture dating back over three-thousand years has its disadvantages. Although much has been discovered about their lives, much more remains to be learned with the expectation and promise of further scrutiny and more scholarship to come in this area.

Published in Ancient Origins Premium September, 2022

References

Brown, F. and Tyrell, W. 1985. A Reading of Herodotus’ Amazons. The Classical Journal. Vol 80. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3296811.

Colarusso, J. 2002. Nart Sagas: Ancient Myths and Legends of the Circassians and Abkhazians. Princeton University Press.

Constantinides, E. 1981. Amazons and Other Female Warriors. The Classical Outlook.

Cunliffe, B. 2019. The Scythians: Noman Warriors of the Steppe. Oxford University Press

Davies, M. 2016. The Aetiopis: Neo-Neoanalysis Reanalyzed. Center for Hellenic Studies, Harvard University.

Dowden, K. 1997. The Amazons: Development and Functions. Rhenisches Museum fur Philologie. Vol. 140. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41234269.

Guliaev, V. 2003. Amazons in the Scythia: New Finds at the Middle Don, Southern Russia. World Archaeology. Vol 35. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3560215.

Herodotus. 2015. The Histories. Trans. Tom Holland. Penguin Books.

Homer. 1998. The Iliad. Trans. Robert Fagles. Penguin Classics.

Mayor, A. 2014. The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women Across the Ancient World. Princeton University Press.