They came to her by land. They came to her by sea. They came to her from the farthest reaches of the Roman Empire and they came to her from close by. Amongst the literati, Hypatia (355-415 CE), acclaimed philosopher and leading mathematician, was a rock star. She was bold, she was beautiful but most of all, she was brilliant. Her students, many of them adherents in the burgeoning new religion, Christianity, adored her and flocked to hear her every word. Congregating not only in the classroom but in the public square and even at her home—just to hear her speak. Hers was the school all serious students throughout the empire wished to attend. But students weren’t the only ones who were captivated by her brilliance. Amongst academics from near and from far, she was the one with whom they sought council.

But how did Hypatia, a woman in a deeply misogynist society, earn such high acclaim? By the tender age of thirty, Hypatia had become a legend within academic circles for fusing the two apparently disparate disciples of mathematics and philosophy together in the classroom. Although well-versed in both disciplines, academics tended to be trained as either philosophers or mathematicians and had schools in one discipline or the other but not in both. Hypatia’s school was the exception. Weaned on mathematics by her father, Theon (335 CE-405 CE), the foremost mathematician in Alexandria, Hypatia would become his best pupil even assisting him in the seminal writings of Euclid and Ptolemy. In fact, Hypatia was so gifted, that her father ceded his school to her—retiring at only fifty-five years of age—when it became apparent that she surpassed him in ability. But for all her mathematical acumen, Hypatia had a strong affinity for philosophy which she believed led to the highest truth. Her robust background in mathematics and philosophy made her school a perfect venue for students who wanted to learn how the two disciplines were unified.

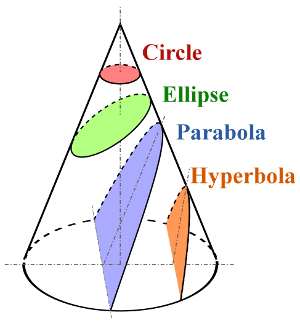

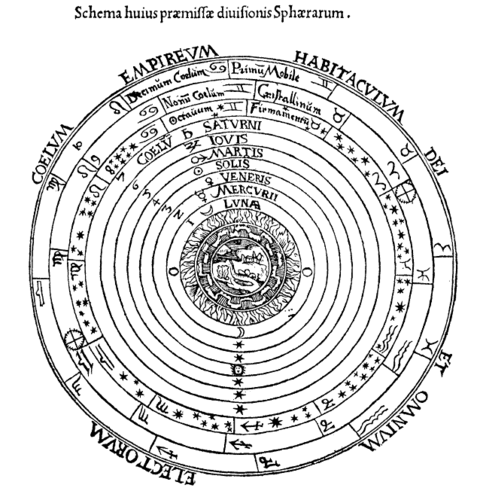

It’s important to have an understanding of what was meant by mathematics and philosophy in ancient times. Today, what two disciplines are more at odds than mathematics and philosophy? Though one is considered practical and useful—in our highly technical world— the other is considered metaphysical and without merit.. While both were thought to be sacrosanct by the ancients, a debate ensued between scholars over which of the two disciplines led to the highest truth. Mathematics, which encompassed arithmetic, geometry, algebra, as well as astronomy, was irrefutable and as such was considered sacred and a path to a higher being or what the ancients termed “the One.” Meanwhile philosophy, a less demonstrable field, was a study employed to instill honor, wisdom and integrity within an individual. The philosophical goal being that this moral code could impart a oneness with the divine. Thus, the goal of both mathematics and philosophy was a transcendent affinity with the sacred, making them both more akin to our notion of religion.

Neoplatonism, the type of speculative philosophy that Hypatia taught, espoused a renunciation of the material world in favor of spirituality. Neoplatonists believed that the materiality of the body and the world in general are things to be overcome. Hypatia herself was exemplar of this creed, choosing to remain celibate so she could focus her energies on scholarship and the satisfaction of the incorporeal world. One famous vignette has her thwarting the unwelcome advances of a student by showing him one of her menstruation rags, quipping “Is this what you love, young man?” Unsurprisingly, his desire for her was quelled. Hypatia’s severe rejection to his advances illustrates how fundamental repudiation of the material world was to Neoplatonism. In this way, it was a philosophy not inconsistent with the essential tenets of Christianity. On account of this compatibility, many of Hypatia’s students were both Neoplatonists and Christian. Although a pagan, Hypatia was nonpartisan and endowed all her students to honor and respect one another and others in the world, regardless of religious affiliation.

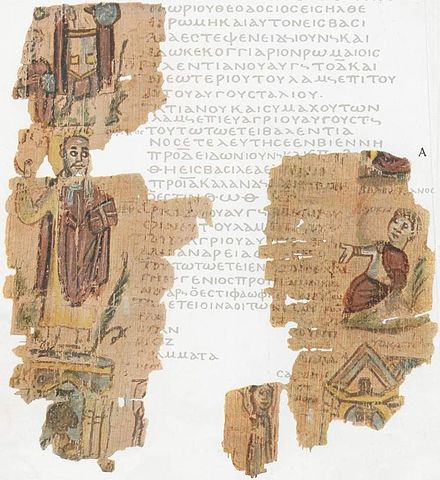

Forasmuch as peaceful coexistence was the order of the day in Hypatia’s school, Alexandria was a tinderbox with disparate factions in conflict with one another; Christian against pagan and Jew, orthodox against heterodox, sectarian against non-sectarian and finally religious authority against civil authority. Under Christian rule, Alexandria, once the definitive center of learning throughout the empire, was fast becoming anti-intellectual and inhospitable to Hypatia and the academic circle in which she traveled. In fact, this burgeoning new religion was oftentimes suspicious of learning, equating it to the work of the devil. Faith in Christ replaced scholarship in this brave new world. An example of this hatred for scholarship was demonstrated in 392 when Theophilus (384 CE-412 CE) Bishop of Alexandria, led a braying mob of Christian zealots in the pummeling of the Serapeum, the city’s premier temple and library complex. Elevated by one-hundred steps on the acropolis of Alexandria, the Serepeum was made of luminous marble and rose above all other structures commanding the city skyscape. Equally impressive, the library within the Serapeum was considered the daughter to the defunct Library of Alexandria housing hundreds of thousands of scrolls. After the extremists razed the Serapeum complex and set fire to the scrolls, the swarm went on a holy mission tearing down other temples, statuary and religious sites, when all was said and done destroying over twenty-five hundred structures in total.

In 414 CE Theophilus died and was succeeded by his nephew, Cyril (378 CE- 444 CE) who made his uncle look conciliatory in comparison. Ruling with an iron-fist from the get-go, he made his wrath known against another enemy of the Christians—the Jews. When some Christians were killed in a skirmish that had broken out between Christians and Jews, Cyril organized an army of thousands called the parabalani. Typically, from the lower rungs of society and oftentimes illiterate, the parabalani were at his call to serve their god, or in this case god’s representative, Cyril. In addition, some in his army were Nitrian monks who traveled to Alexandria from the desert fired up in righteous religious indignation against non-Christians. Both groups had a flagrant reputation for violence.

When the stone-hurling monk was apprehended, Orestes had him publicly tortured and the monk ultimately died. In true form, Cyril used the monk’s death in a propaganda campaign against the governor further fueling the fire between the disparate factions.

Attempts at reconciliation between the two leaders ended in failure. Through it all, the governor sought counsel from the wisest person in the land who stood resolutely by his side. But Cyril’s supporters saw Hypatia’s advocacy on Orestes’ behalf not as uniting but as dividing. Alexandria’s most acclaimed pagan was an easy target who they blamed for the continuing rift between the two men.

Then the rumors began. She has an undue influence on Orestes, they blustered. She’s bewitched him with her sorcery, others moaned. She is teaching idolatry, they shrieked. Calling her a witch, they even used her famed astrolabe against her saying it was an instrument of Satan. The cacophony of outcries against her became deafening. Then it happened. Demonstrating once again how easy it is to harm those who have been dehumanized.

On her daily ride through the city on that bright and sunny day in March of 415, Hypatia had set off for school in her chariot. As was usual for her, her mind was a million miles away. Perhaps she was thinking about her next seminar; about some philosophical dictate or mathematical law she would discuss in class. Being an exemplary teacher, her fortunate students were never far from mind.

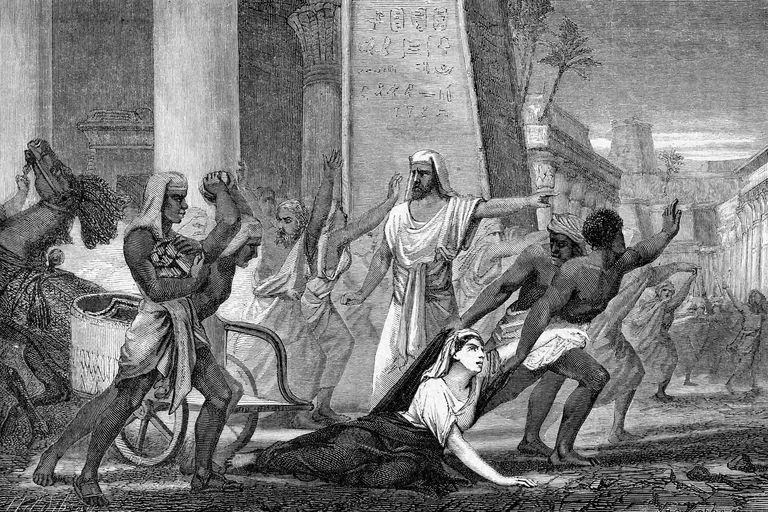

But her introspection was savagely broken when she found herself physically confronted by a howling mob under the leadership of Peter, a church magistrate. Because she was not a civil authority, she lacked the security detail that Orestes enjoyed. But up until then, no academic had needed such protection in Alexandria.

From the beginning, it was violent. They ordered her off her chariot, then dragged her through the streets and into a church. She must have tried to reason with them, but her reasoning fell on the deafened ears of the righteous. After all theirs is the will of god. They tore the clothes off of the “luminous child of reason” and in God’s house they flayed her with the jagged edges of roofing tiles.

As if that were not enough, while still alive and breathing, they gouged out her eyes. Once dead, they further violated her by cutting her body into pieces and parading the pieces throughout the streets of Alexandria. Finding rest, at long last, on a pyre. In fact, violent criminals were treated with more forbearance than Alexandria’s most prominent intellectual.

From the farthest reaches of the empire to close by, both Christian and non-Christian alike were in an uproar about the abhorrent slaying of the greatest mathematician of the day. It was an outrage. Academics were considered inviolable because they enhanced the community with their scholarship and wisdom. But if being an academic was not enough to protect her, Hypatia was also an elite woman. A rank by itself deemed sacrosanct.

How could something of this magnitude happen to one as beloved as she? But the truth is that Hypatia was part of a dying breed, the last champion of a seven-hundred-year academic tradition vanishing under a tidal wave of anti-intellectual religious dogma. After Hypatia’s death, many pagan academics fled Alexandria in search of more tolerant cities. But eventually the tidal wave could be felt throughout the empire with religion replacing philosophy and clergy replacing academics.

Devastated, Orestes soon left public life. But Cyril’s star was still rising. Although never formally charged in Hypatia’s violent end, if not for the anti-pagan fervor he stirred up amongst his minions, such a horror would never have taken place. Following her death, Cyril was given the honorary moniker “the new Theophilus” by his jubilant followers for quashing the “last remnants of idolatry.” Under his continued leadership, Alexandria became an important Christian hub with Cyril eventually canonized as a saint. To this day, he is venerated in the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches.

Published on Classical Wisdom

According to the primary sources, Hypatia was a versatile, inspiring, and courageous scholar and teacher, but she made no original contributions to mathematics or science. She was notable only for her gender and her gruesome murder.